A note on this page's publication date

This page describes room for more funding for GiveWell's top charities in 2019; it has not been updated since its publication.

Published: November 2019

Our understanding of how each top charity would use additional donations is a key input into our recommendations. We direct donors to support our top charities and want to ensure those funds will be used well.

Below we summarize our understanding of how each of our top charities would use additional funding. A top charity's "funding gap" refers to the difference between the funding we project the charity will receive from its regular donors and the total amount the charity believes it can use effectively to implement and/or expand its programs.

We don't recommend that donors fill these funding gaps equally. Charities' ability to cost-effectively use additional funding varies. In addition, charities' plans and resources often shift, particularly following the period at the end of the calendar year when the volume of donations is highest.

We recommend that donors who want their funding directed to the funding gap we believe is most cost-effective give to "Grants to recommended charities at GiveWell's discretion," which we will grant quarterly to a top charity or charities, according to where we see the highest-impact funding need.

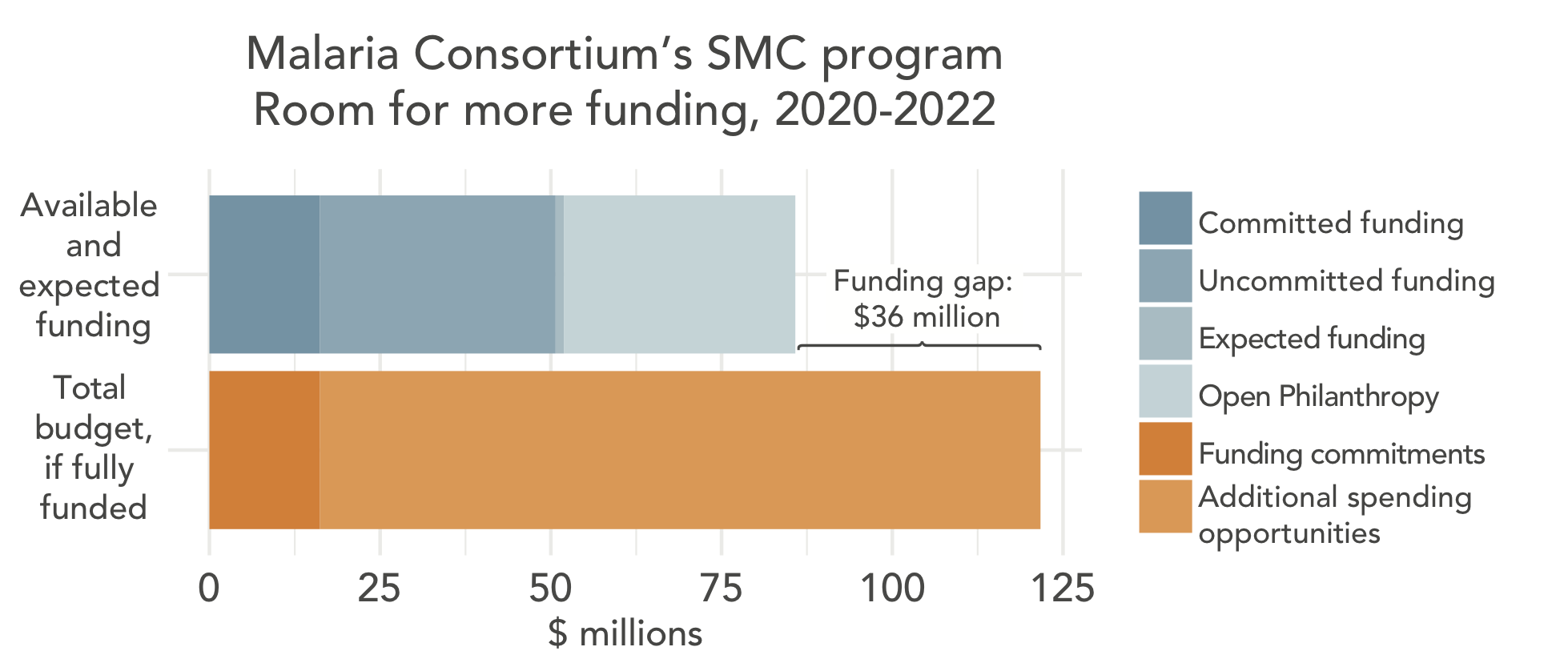

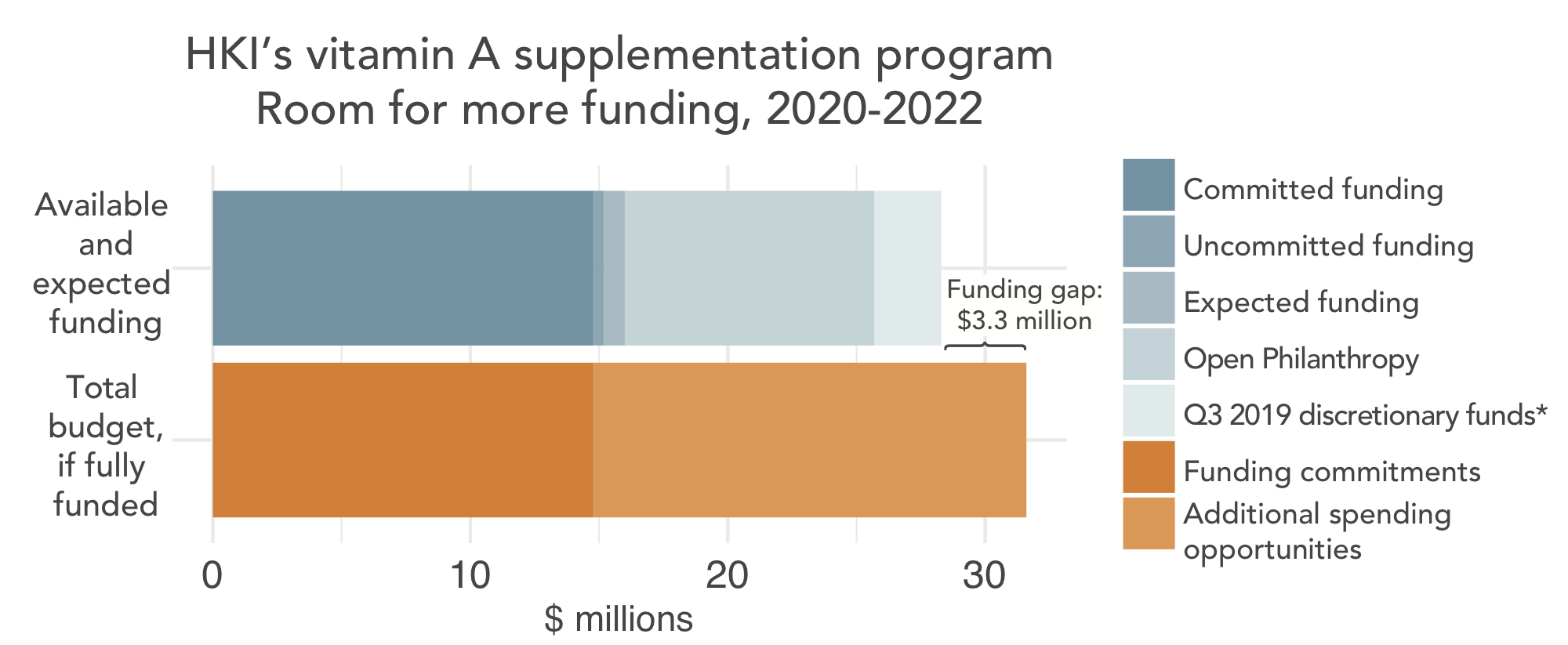

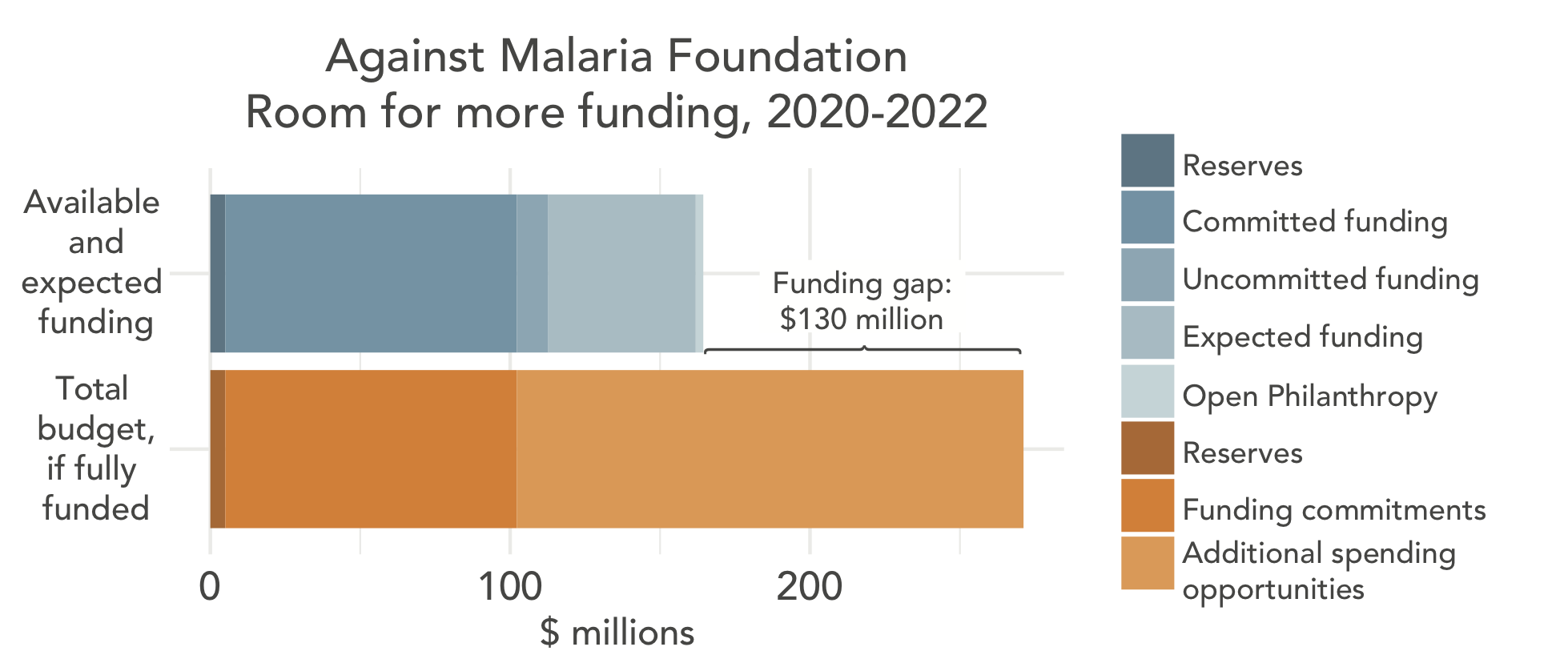

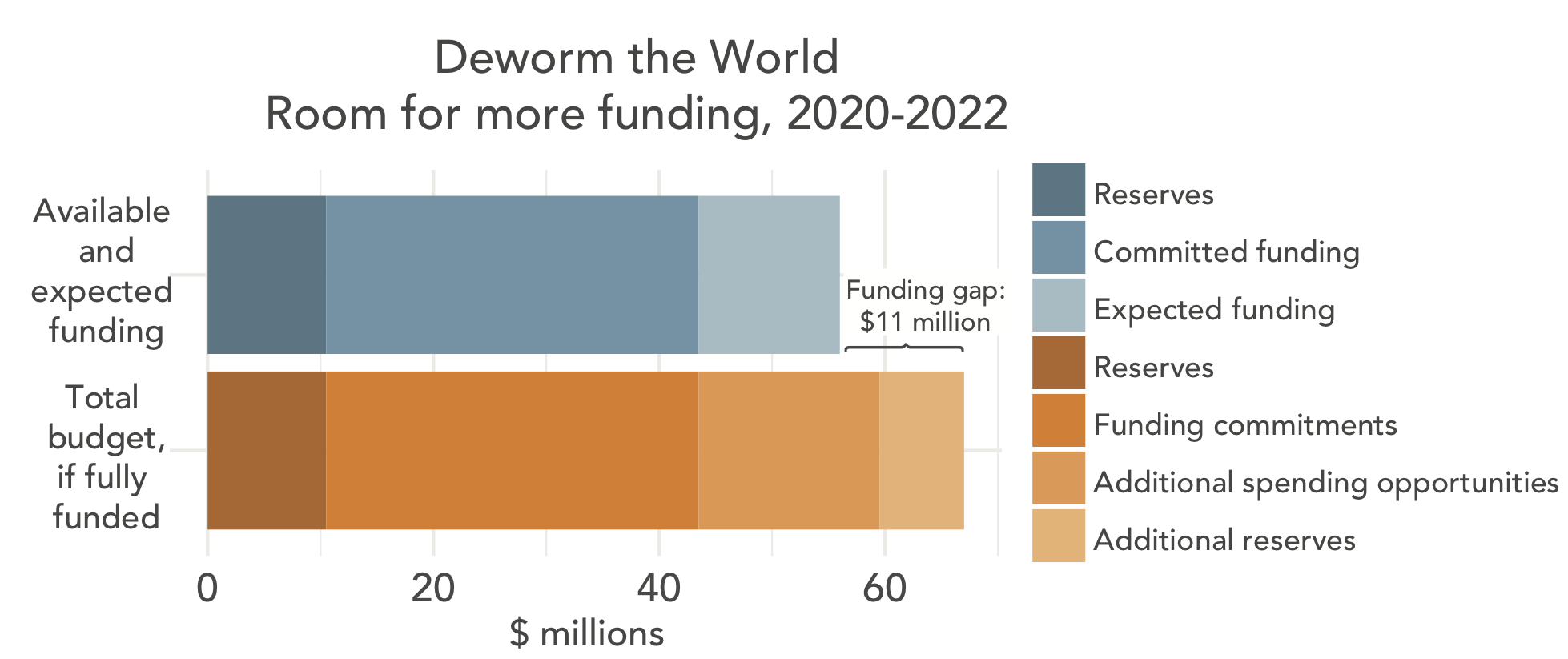

The charts below use different scales on the horizontal axis.

Table of Contents

- A note on this page's publication date

- Notes on terminology used on this page

- Summary

- Malaria Consortium's seasonal malaria chemoprevention program

- Helen Keller International's vitamin A supplementation program

- Against Malaria Foundation

- Evidence Action's Deworm the World Initiative

- Sightsavers' deworming program

- END Fund's deworming program

- GiveDirectly

- SCI Foundation

Notes on terminology used on this page

Terminology used in tables

Size of funding gap: These estimates use the total amount that each top charity has told us it could use productively in the next three years, less the total amount of funding it has or we project it will have in that period. These estimates incorporate grants we recommended that Open Philanthropy, a philanthropic organization with which we work closely, make to our top charities in November 2019.

Adjusted cost-effectiveness: This is the output of our cost-effectiveness model for each funding gap. The adjustments include: leverage of or fungibility with other sources of funding; estimates of the likelihood that supplies are wasted, the likelihood that available monitoring is unrepresentative, and the likelihood that funds are not used for the intended program (see "downside adjustments" in our model); and guesses about the size and direction of program effects that are not modeled (see "inclusion/exclusion" in our model).

Multiples of cash transfers: We express our cost-effectiveness estimates in terms of how many times more cost-effective a program is than using the same amount of funding to deliver unconditional cash transfers to very poor households. We model the cost-effectiveness of cash transfers as delivered by GiveDirectly.

Our assessment of relative organizational strength: We compare our charities on a number of qualitative dimensions that are discussed on this page.

Terminology used in charts

Committed funding: Cash on hand that an organization has committed to specific future uses. Equal to funding commitments.

Funding commitments: Expenses that an organization has set aside funding for. Equal to committed funding.

Uncommitted funding: Cash on hand that an organization has not committed to specific future uses.

Expected funding: Funding that we project an organization will receive that is not due to our recommendation for how donors can achieve the most impact on the margin.

Open Philanthropy: Grants we recommended that Open Philanthropy make to top charities in November 2019.

Additional spending opportunities: Programs that an organization could support, but to which it has has not yet committed funding.

Reserves: Funding that an organization does not expect to use unless it faces an unexpected shortfall. We discuss our uncertainty about how to account for funding reserves here.

Summary

Highest priority gaps

The table below lists the highest priority funding gaps we've identified, after accounting for grants we recommended that Open Philanthropy make to top charities in November 2019, in order of priority.

| Summary of funding gap (details below) | Size of funding gap | Adjusted cost-effectiveness (multiples of cash transfers) | Our assessment of relative organizational strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Malaria Consortium: Continue funding seasonal malaria chemoprevention in four countries in 2022 | $36 million | 17 | Relatively strong among top charities |

| Against Malaria Foundation: Continue to support current countries in 2021-2022 | $36 million | 17 | Relatively weak among top charities |

| Helen Keller International: Begin support for vitamin A supplementation (VAS) in Cameroon | $1.8 million | 17 | Average among top charities |

| Helen Keller International: Expand support for VAS to additional counties in Kenya | $1.5 million | 13 | Average among top charities |

Other funding gaps

We prioritize filling these funding gaps less highly than those above.

| Summary of funding gap (details below) | Size of funding gap | Adjusted cost-effectiveness (multiples of cash transfers) | Our assessment of relative organizational strength | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

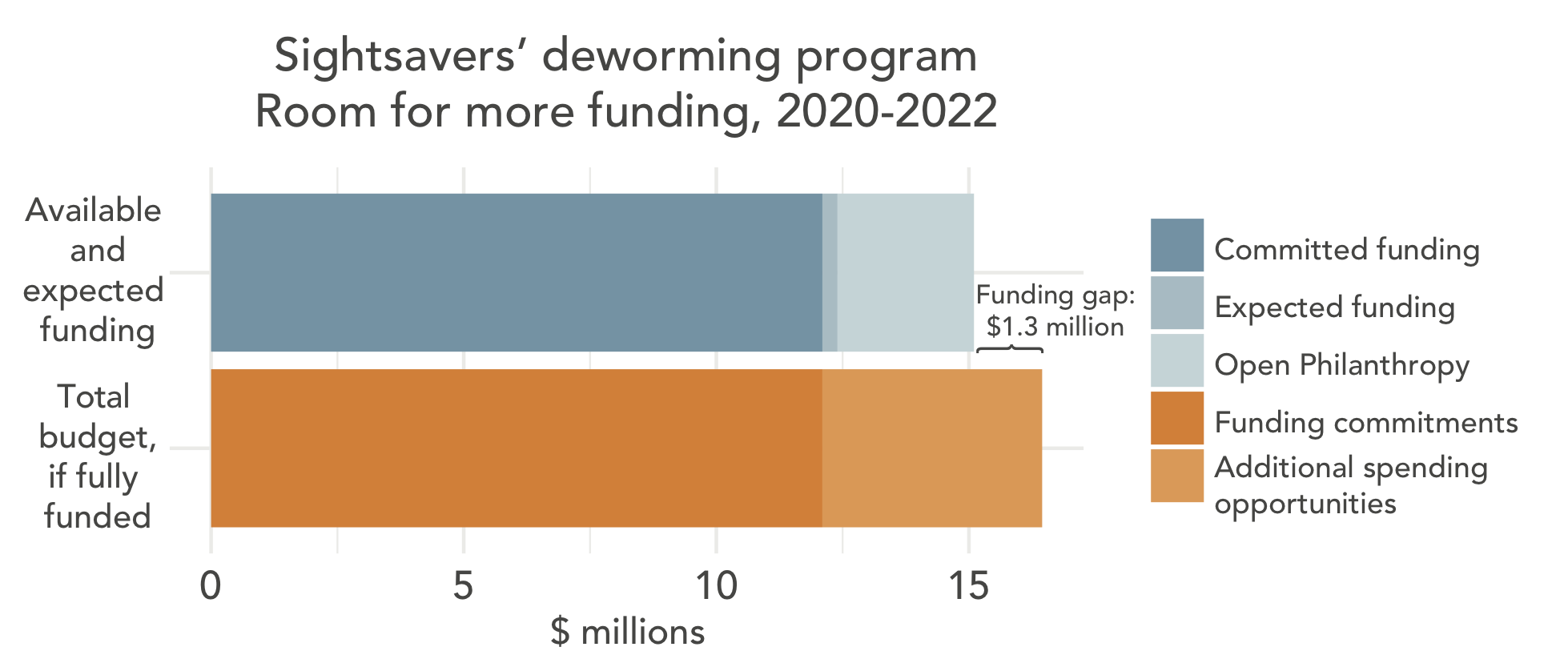

| Sightsavers: Begin support for deworming in Senegal | $1.3 million | 9 | Relatively weak among top charities | We have not yet modeled the cost-effectiveness of deworming in Senegal specifically; this is the average cost-effectiveness for Sightsavers' current deworming programs. |

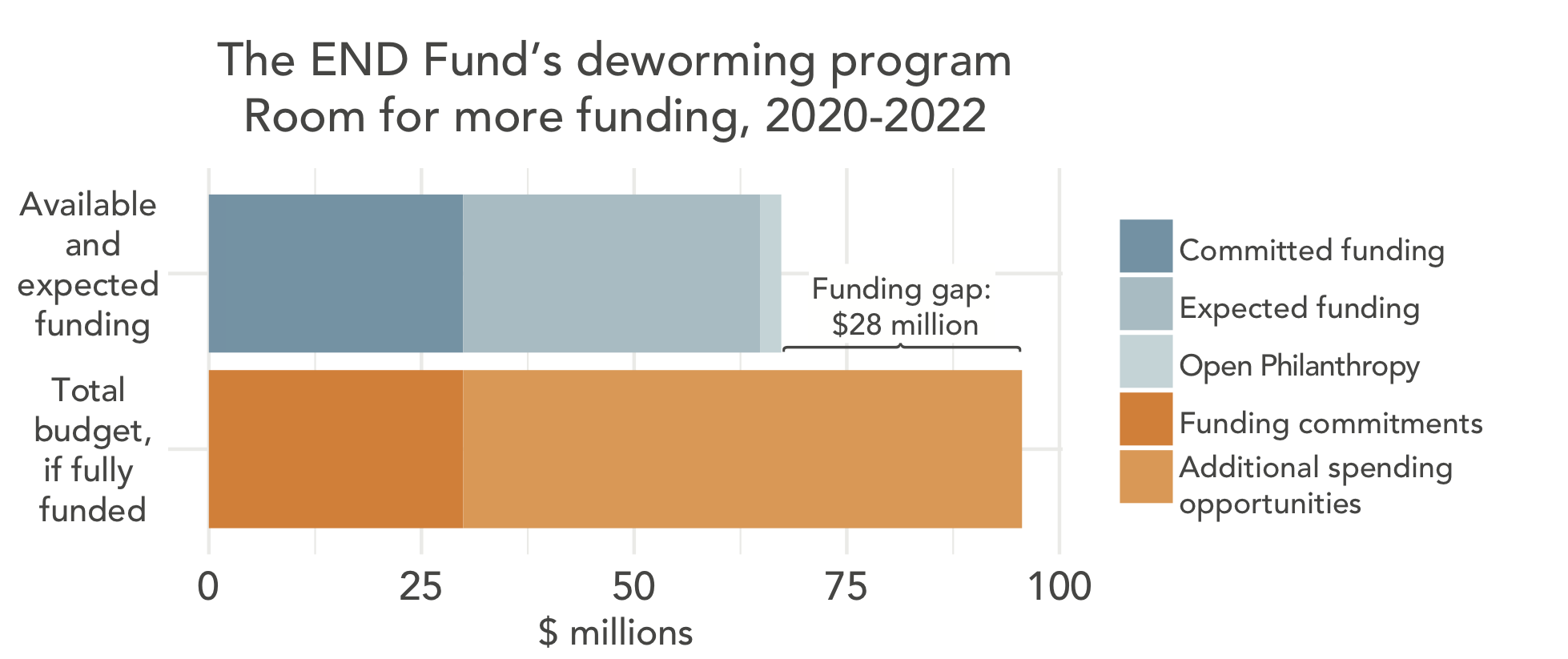

| END Fund's deworming program: Maintain support to 15 countries and expand support in nine countries | $28 million | 5 | Average among top charities | We have modeled the END Fund's cost-effectiveness as lower than that of other top charities that work on deworming, and we understand how it would use additional funding less well. |

| Evidence Action's Deworm the World Initiative: Continue supporting deworming in (1) India and (2) Pakistan in 2022 | $3.5 million | (1) 100, (2) 8 | Relatively strong among top charities | Deworm the World holds funding in reserve sufficient to cover these gaps and give it a three-year funding runway. We have generally used three years as the maximum funding runway in our analysis and do not believe that a longer funding runway in these programs will affect Deworm the World's plans in the next year. |

| Against Malaria Foundation (AMF): Not-yet-identified opportunities | Tens of millions of dollars | 17 | Relatively weak among top charities | AMF believes it could use a large amount of funding in countries it has not worked in before, but it has not yet identified which countries these would be. The cost-effectiveness given here is the average cost-effectiveness for AMF's recent and upcoming distributions. |

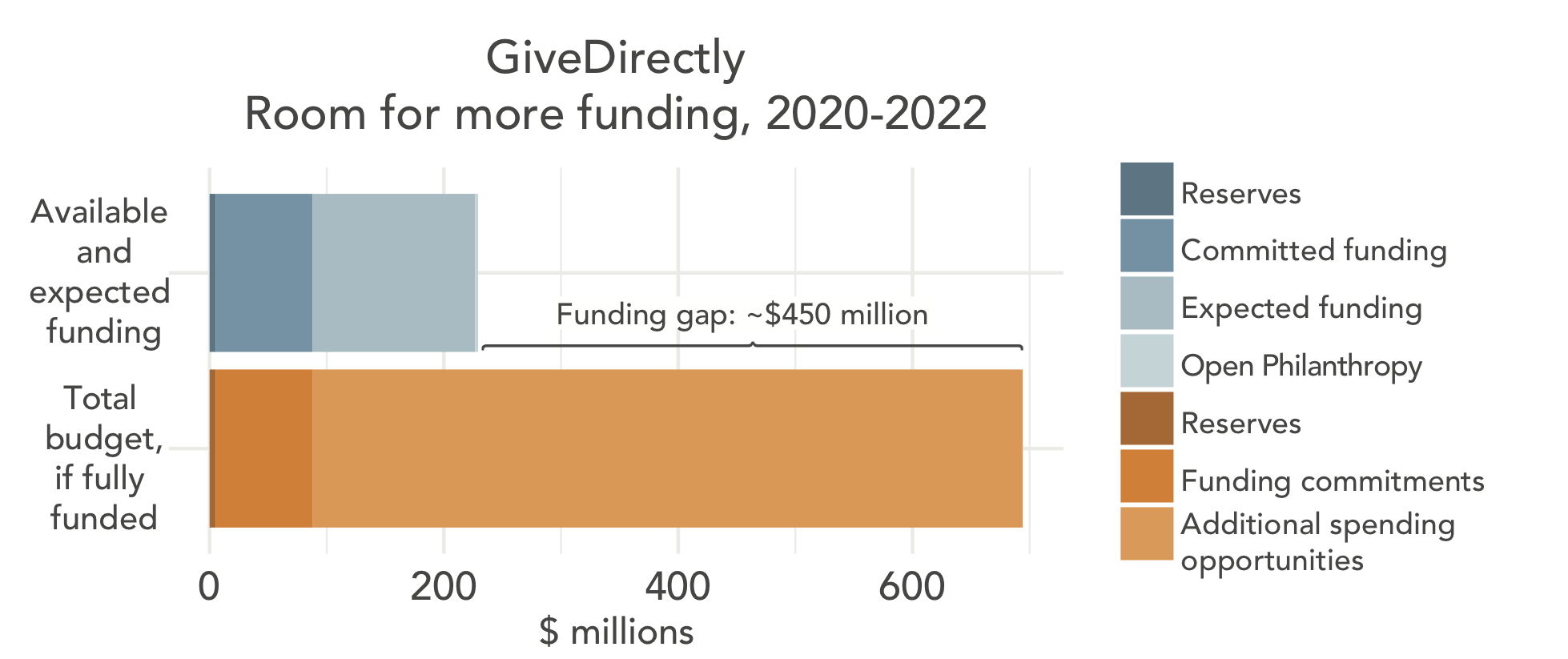

| GiveDirectly | Over $450 million | 1 | Relatively strong among top charities | Our cost-effectiveness estimates suggest our other top charities are substantially more cost-effective. |

Malaria Consortium's seasonal malaria chemoprevention program

On the margin, Malaria Consortium expects to use additional funding to:

- Continue funding seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) in four countries: Nigeria ($11.6 million), Burkina Faso ($11.3 million), Chad ($10.2 million), and a fourth, to-be-determined country ($2.5 million). Malaria Consortium's SMC program in its three current countries of operation is funded through 2021 at a scale of about $30 million per year. Malaria Consortium will need to raise at least that amount to maintain its work in 2022. It estimates its 2022 budget at $33 million, or $36 million if it expands to a fourth country. It will need to order drugs for 2022 by mid-2021 and may benefit from having funding in place sooner to start planning for 2022.

For sources and analysis, see our review of Malaria Consortium's SMC program.

Helen Keller International's vitamin A supplementation program

On the margin, Helen Keller International (HKI) expects to use additional funding to:

- Begin support for vitamin A supplementation (VAS) in Cameroon ($1.8 million): HKI told us that in the latter half of 2018, VAS campaigns were skipped among 70% of the population of Cameroon; HKI was not supporting VAS in the country at the time. HKI is seeking funding to support VAS campaigns in two regions of Cameroon in 2020-2022.

- Expand support for VAS to additional counties in Kenya ($1.5 million): HKI has told us that about half of the counties in Kenya do not receive external support for VAS campaigns and that VAS campaigns in the unsupported counties likely achieve low (~20%) coverage rates. HKI is seeking funding to provide technical and financial support in 2020-2022 in counties that do not currently receive external support for VAS campaigns.

*In the third quarter of 2019, GiveWell received $2.6 million from donors for granting at GiveWell's discretion. In November 2019, we recommended that the GiveWell Board of Directors vote to grant this funding to HKI for VAS.

For sources and analysis, see our review of HKI's vitamin A supplementation programs.

Against Malaria Foundation

On the margin, AMF expects to use additional funding to:

- Continue to support current countries in 2021 ($17.8 million): Guinea, Malawi, Ghana, and parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Papua New Guinea will be due to replace nets in 2021. We project that, while AMF will raise funds to cover perhaps two-thirds of the funding needed for these distributions, it is likely to have a large gap remaining.

- Take advantage of not-yet-identified opportunities (very roughly $50 million a year in each of the next two years): If it has available funding, AMF will seek out opportunities to work in countries it has not partnered with to date. It estimates that it could potentially use tens of millions of dollars a year for new opportunities.

- Continue to support current countries in 2022 ($17.8 million): Parts of the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Papua New Guinea will be due to replace nets in 2022. We project that AMF will raise funds to cover about a third of the funding needed for these distributions, leaving it with a large gap.

For sources and analysis, see our review of AMF.

Evidence Action's Deworm the World Initiative

On the margin, Deworm the World expects to use additional funding to:

- Continue supporting deworming in India ($1.7 million): Additional funding would allow Deworm the World to have a three-year funding runway for its work (extending from 2021 to 2022), which it seeks in order to ensure the stability of its work and partnerships.

- Continue supporting deworming in Pakistan ($1.8 million): Additional funding would allow Deworm the World to have a three-year funding runway for its work (extending from 2021 to 2022), which it seeks in order to ensure the stability of its work and partnerships.

- Build additional funding reserves ($7.5 million): Deworm the World is seeking to have funding in reserve equal to its annual budget. This funding would be in addition to the two or three years of funding runway that it has for each of the programs (Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan, and some of the states in which it works in India) that have been supported by GiveWell-directed funding, and would be used to further backstop those programs (in the event of an unexpected shortfall) as well as to backstop programs not supported by GiveWell-directed funding that may have shorter funding runways. It currently holds $10.5 million in reserve and is seeking an additional $7.5 million for this purpose.

For sources and analysis, see our review of Deworm the World. We did not recommend that Open Philanthropy make a grant to Deworm the World in November 2019 (more).

Sightsavers' deworming program

On the margin, Sightsavers expects to use additional funding to:

- Begin support for deworming in Senegal ($1.3 million): In Senegal, districts that require treatment for onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis have delivered deworming through integrated neglected tropical disease programs. Sightsavers has identified a funding gap for deworming in districts that do not require treatment for the other neglected tropical diseases.

- Sightsavers may have opportunities to reach additional children with deworming treatments in areas partially supported by the UK's Department for International Development (DFID) and may have future opportunities to extend deworming in Chad, Burkina Faso, and other countries, if it had funding available. We do not currently have estimates of the costs of these programs.

For sources and analysis, see our review of Sightsavers' deworming program.

END Fund's deworming program

On the margin, the END Fund expects to use additional funding for deworming to:

- Maintain support to 15 countries ($3.9 million over three years): We estimate that the END Fund will have a funding gap of $3.9 million over the next three years to continue supporting the neglected tropical disease (NTD) projects that include deworming that it is supporting in 2019.

- Expand support in nine countries ($24 million over three years): The END Fund has identified opportunities to expand its support for NTD projects that include deworming in nine countries over the next three years.

For sources and analysis, see our review of the END Fund's deworming program.

GiveDirectly

On the margin, GiveDirectly expects to use additional funding to:

- Provide cash transfers in Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, Malawi, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

- Flexibly respond to opportunities to conduct special cash transfer projects with partners. We discussed GiveDirectly's past and ongoing projects with partners here.

Over 2020-2022, we estimate that GiveDirectly could productively use several hundred million dollars more than we expect it to receive—we roughly estimate $450 million based on GiveDirectly's expectations of its capacity to scale.

For sources and analysis, see our review of GiveDirectly.

SCI Foundation

As of November 2019, we consider SCI to have no identified funding gaps. SCI is seeking additional information on whether funding gaps exist in a set of countries for which SCI will receive funding from DFID to treat neglected tropical diseases. We may increase our assessment of SCI's room for more funding in the next six months as a result.

We and SCI plan to have further conversations in 2020 about whether SCI has a funding gap after it has sufficient information to project funding needs and availability in Ethiopia, Malawi, Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda.

For sources and analysis, see our review of the SCI Foundation. We did not recommend that Open Philanthropy make a grant to the SCI Foundation in November 2019.