We have published a more recent review of this organization. See our most recent report on VillageReach.

VillageReach aims to improve the systems that distribute medical supplies to rural areas in Africa, so that life-saving supplies get to those who need them. Its programs include both technical support staff and changes in logistical setups (such as moving from a system in which health clinics collect their own supplies to a centralized delivery system).

VillageReach is a relatively small and young organization. We believe its activities have had and will have significant impact, under $1000 per infant death averted.

Table of Contents

- What do they do?

-

Does it work?

- Delivery of vaccines and medical supplies

- Increases in immunization coverage

- Were improvements attributable to VillageReach?

- Bottom line on the Cabo Delgado program between 2001-2008

- Can improvements be maintained?

- Nampula activities

- Possible negative/offseting impact

- What can be expected of future activities?

- What do you get for your dollar?

- Room for more funds?

- Financials/other

- Sources

What do they do?

Broadly, VillageReach aims to improve the logistics - particularly delivery of medical supplies - for health systems in rural areas.1

Pilot project

VillageReach, which was founded in 2000,2 conducted a demonstration of its core logistics program in the Cabo Delgado province of Mozambique from April 2002 to March 2007.3 The Cabo Delgado project officially became the local government's responsibility in 2007,4 but VillageReach may soon resume responsibility due to problems under government management.

VillageReach's pilot project in Mozambique is the focus of our review because it is similar to the future activities most likely to be funded with donations. It included:5

- Transportation vehicles: "Created multi-modal transport network including land cruisers, motorcycles and bicycles. Staff inspects and repairs equipment on monthly visits."

- Cold chain: "Introduced reliable, low maintenance and cost-effective refrigerators in clinics."

- Injection safety equipment: "Installed propane burners for sterilization, incineration points and needle removers to ensure safe disposal of used syringes."

- Clinics' energy access: "Provided lighting for nighttime care, refrigerators, and sterilizers at clinics."

- Supplies-tracking: "Partnered with Iridium to utilize their global satellite system, introduced communication system in trucks to enable near, real-time inventory tracking."

- Training: "Trained community representatives to provide basic health care."

- Creating a for-profit enterprise to improve energy supply: "Established VidaGas, a Mozambican propane distribution company to reliably supply energy to clinics, businesses and households."

Nampula expansion

In 2006, VillageReach began to replicate the project in a second province in Mozambique, Nampula.6 It handed off the project to a local nonprofit in January 2007.7

Future activities

VillageReach's planned activities consist of:

- Further activities in Mozambique, similar to the pilot project. These are the main activities VillageReach is seeking to raise donations for.

- A variety of contract engagements. Specific parties have offered VillageReach funds to carry out projects in different parts of the world, all on the theme of improving health system logistics but sometimes different in many ways from the pilot project discussed above. With one exception, all of these projects are fully funded by the party in question, and VillageReach does not seek donations for them. As such, we have not deeply examined these programs (with the exception of the one for which donations are sought).

- An allocation of operating expenses (salaries, etc.) to development of new initiatives.

Further activities in Mozambique

VillageReach is currently planning to (a) reactivate its support role in Cabo Delgado, due to problems under government management; (b) continue to push for the government to adopt its model; (c) expand support to the neighboring Niassa province of Mozambique.8 It plans to conduct monitoring and evaluation similar to what it did for its pilot project, assessing before-and-after vaccination coverage for both provinces as well as a "comparison" province where it will not operate.9

As of October 26, 2009, VillageReach needed an additional $172,830 to fund this plan for the next year. It also has the option of working in only one province (Cabo Delgado or Niassa, not both), in which case it would face no funding gap.10

VillageReach also provided an outline of how much additional funding it would need to expand into additional provinces in Mozambique other than Cabo Delgado and Niassa. It has estimated that it can begin a 3-year project in a new province each year for the next 8 years, with each such project costing just over $1.1 million per year.11

Contract engagements

Specific parties have offered VillageReach funds to carry out projects in different parts of the world, all on the theme of improving health system logistics but sometimes different in many ways from the pilot project discussed above. Notes on these engagements follow:

| Funder | Bayview Foundation | [Currently confidential] | [Currently confidential] | [Currently confidential] | Global Fund | Medicines for Malaria Ventures | John Snow Inc. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Area | Malawi (Kwitanda province) | South Africa (KwaZulu Natal province) | India | Senegal | Nigeria | Malawi (Kwitanda province) | TBD |

| Description | SMS-based logistics for community health workers | General health system logistics | Vaccine-focused health system logistics | General health system logistics | Assessment of health system, prior to investment in malaria medicines | SMS-based logistics for community health workers | Operations research |

| Expenses | $249,961 | $120,797 | $233,569 | $131,656 | $188,325 | $36,981 | $50,000 |

| Fully funded? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Needed from donations | $0 | $100,000 over 3 yrs | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 | $0 |

| More information | VillageReach, "President's Report;" VillageReach, "2010 Budget." | VillageReach, "President's Report;" VillageReach, "2010 Budget";' VillageReach, "South Africa Proposal." | VillageReach, "President's Report;" VillageReach, "2010 Budget." | VillageReach, "President's Report;" VillageReach, "2010 Budget." | VillageReach, "Nigeria Budget;" Becca Miller, e-mail to GiveWell, December 18, 2009. | VillageReach, "Medicines for Malaria Ventures Proposal." | VillageReach, "John Snow Proposal." |

Some additional notes on the South Africa project, as this project is relevant to individual donors:

- VillageReach seeks to improve the general health system capacity in the Zululand district of the KwaZulu Natal province of South Africa12 through "business process mapping and optimization, streamlining data collection, staff training, mentoring, and supervision, expanding quality improvement methodology, and the identification of innovative uses for information and communication technology in patient care coordination at the clinic level."13

- VillageReach's specific plans for assessing its impact are unclear to us. It states that it plans on a "A baseline and endline survey to gauge the outcomes and impact of the project" as well as "track[ing] output and outcome indicators that could include stock levels of key commodities, accuracy and frequency of data collection in the clinics, frequency of supervision visits, reports of data use and understanding by clinic staff, and satisfaction of clinic staff with the program."14 It is unclear to us exactly what the impact survey will consist of and, thus, how VillageReach will assess whether it has achieved its long-term goal of "80% improvement in identified primary healthcare indicators."15 On a more short-term basis, it is also unclear to us how VillageReach plans on assessing "accuracy and frequency of data collection in the clinics."

Other plans

VillageReach also faces a funding gap for development of new programs and social businesses, as well as ongoing support to VidaGas, a gas delivery business developed as part of its pilot program. These needs total $192,016 as of the most recent budget we have (details below), and we have been told that they are a lower priority than the Mozambique activities detailed above.16

Does it work?

This section focuses on VillageReach's pilot project in Cabo Delgado, then briefly discusses its work in Nampula and what can be expected of its future activities.

One of VillageReach's primary methods of evaluating success is through tracking the progress made in administering basic immunizations. Such immunizations are a proven, cost-effective way to improve health and save lives in the developing world (more here), and so success in increasing immunization coverage - alone - likely constitutes, in our view, success in saving lives.

Below we examine evidence provided by VillageReach including (a) reporting on vaccines and equipment delivered, progress in vaccination coverage rates, and health clinic inventories; (b) an independent evaluation17 of VillageReach's impact. We conclude that VillageReach's pilot project has been effective in increasing vaccine coverage.

Delivery of vaccines and medical supplies

A key component of VillageReach's model is a shift from a "collection-based" to a "delivery-based" supply system: rather than clinics' being responsible for picking up their own supplies, VillageReach's logistics team delivers supplies and provides other logistical support.18

The tables below provide data on the goods VillageReach delivered to Cabo Delgado between 2004 and 2007.19 (Note that the project began in April 2002; we aren't sure why data has not been provided pre-2004.)

| Vaccine type | August – December 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | January – April 2007 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCG | 39,000 | 129,200 | 131,260 | 43,700 | 343,160 |

| DPTHpB | 37,640 | 173,310 | 171,330 | 47,020 | 429,300 |

| Polio | 87,800 | 244,480 | 303,730 | 79,020 | 715,030 |

| Measles | 19,580 | 61,210 | 77,130 | 18,390 | 176,310 |

| Tetanus | 42,630 | 182,720 | 189,230 | 61,290 | 475,870 |

| Equipment/Gas | August – December 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | January – April 2007 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syringes (0.5 ml) | 52,793 | 134,757 | 60,073 | 18,202 | 265,825 |

| Syringes (0.05 ml) | 7,769 | 25,523 | 20,570 | 7,696 | 61,558 |

| Syringes (5ml) | 991 | 15,209 | 6,684 | 2,650 | 25,534 |

| Safety boxes | 906 | 1,517 | 2,105 | 22 | 4,550 |

| Gas (in cylinders) | 485 | 2,091 | 2,286 | 692 | 5,554 |

| Gas (in Kg) | 2,668 | 11,501 | 12,573 | 3,806 | 30,548 |

Increases in immunization coverage

The charts below show that (a) the number of children receiving DTP-3 (third dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine20 ) immunizations increased; (b) the number of children who "dropped out" during the DTP-3 sequence - that is, they received one, but not all doses - fell; (c) reported "stock-outs" - centers with no inventory of the vaccine - fell significantly over the course of VillageReach's pilot project, which ran from April 2002 to March 2007.21 . Charts are taken from Kane 2008.22

Were improvements attributable to VillageReach?

The evaluation of the project notes that during this time period, "Mozambique and most sub-Saharan African countries achieved significant improvements in their DTP-3 coverage, probably due to GAVI and its support for infrastructure development and provision of new vaccines and safe injection equipment."23

To evaluate the question of VillageReach's role in improvements, we look at three types of information:

- Reports from VillageReach about the problems interfering with immunizations in Cabo Delgado before their arrival.

- An evaluation report published by VillageReach explicitly focused on addressing this question, comparing the change in immunization coverage rates in Cabo Delgado to that of another province in Mozambique, Niassa.

- Examining the changes in immunization coverage in several countries in Africa over this period to put the observed change in context.

We also observe that the above charts showing "stock-outs" above have stock-outs falling from a very high level prior to the start of the project to a very low level shortly after the project began. While it is possible that this change occurred for some reason other than VillageReach's involvement in the area, such an outcome seems unlikely.

VillageReach reports of pre-arrival conditions

VillageReach provides a report of the obstacles to immunization coverage in Cabo Delgado before its arrival. We would prefer to have better documentation of these conditions, but nevertheless, we believe the report offers some support to the idea that VillageReach's services were needed in Cabo Delgado.

VillageReach reports,

- Intermittent closing of health facilities during business hours so health workers could pick up vaccines and supplies.

- Challenges securing transport to go to the DPS cold stores. Each district generally had one vehicle, which was for all health service trips by all health system personnel, and was also the ambulance in case of emergencies. Often, when the vehicle was needed to pick up or deliver vaccines, it was out on an emergency, in use by someone else for some other health-system function, broken down, or out of gas.

- Difficulty maintaining proper vaccine temperatures during transport.

- Uncoordinated vaccine supply requirements.

- Frequent stock-outs of vaccines in health facilities.

- Funds were often liberated late – both quarterly from the provincial level to the districts, and monthly from the district administrator to the PAV Chief who needed to purchase gas for the refrigerators, fuel up the district vehicle, and pick up and distribute vaccines.24

In 2002, before starting work, VillageReach performed an assessment of access to vaccines in Cabo Delgado province.25 This report claims that, in 2002, there were 22 health facilities in the three districts in Cabo Delgado that VillageReach assessed.26 Of these 22, 4 did not offer access to vaccination services:27 two facilities because they did not have access to a cold chain; 1 because it lacked personnel; and 1 for other reasons.28

VillageReach evaluation document

VillageReach compared improvements in vaccine delivery in Cabo Delgado to improvements in the nearby Niassa province, which was not served by VillageReach.29

- Baseline data collection: Because VillageReach did not have baseline data (i.e., data from a time prior to the start of the project) available for Niassa, it used data from the 1997 and 2003 Demographic and Health Surveys, which surveyed a large number of households and provided data on DTP-3 coverage.30

- Outcome data collection: Evaluators randomly selected households in the treatment area (Cabo Delgado province), including 474 children.31 Evaluators then also randomly selected households in the comparison area (Niassa province), thereby including 571 children in the evaluation.32

- Results: The study found that DTP-3 coverage rates increased substantially in both provinces during this period, but rates improved more in Cabo Delgado (treatment area) than Niassa (control area). The chart below shows the change in coverage rates in the two areas during this time period; the 1997 and 2003 data points are based on Demographic and Health Surveys, while the 2008 data points are from VillageReach's independent data collection.33

On one hand, we believe that this chart creates an inflated picture of VillageReach's impact. We have reason to believe that there were significant improvements in immunization coverage between 1997-2001 that were more related to Cabo Delgado's recovery from the aftermath of a civil war than to VillageReach's activities.34 However, the jump to extremely high levels of coverage as of 2008 - a change not mirrored in the nearby province - give some reason to attribute impact to VillageReach.

The evaluation report is forthright about many limitations of this comparison analysis, including limited sample size, uncertainty about the appropriateness of Niassa as a "comparison province," and issues with taking baseline and endpoint data from different sources.35 However, it says that its way of comparing the results of surveys done with different methodology is "is consistent with international practice." And it concludes that it appears that the Project is responsible for the immunization coverage rising more in the treatment province, Cabo Delgado, than in the comparison province Niassa; although "additional information about the conditions in Niassa compared to those in Cabo Delgado is needed to better understand and interpret the comparison data."36 It also notes that "it is ... unlikely that the activities of other NGO's, which are not very involved in immunization activities in Cabo Delgado, were responsible for the improvement."37 (Note, however, that it does not discuss the confounding effect of the civil war recovery that we discussed above.)38

Our comparison of Cabo Delgado to other areas in the developing world

We took a broader look at changes in African immunization coverage over the time period in question in order to further investigate the idea that Cabo Delgado's improvements may simply have reflected a wider phenomenon. Using the Demographic and Health Surveys (Measure DHS),39 we collected data on DTP-3 immunizations for countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.40

The table below summarizes this data, sorted by the country's arithmetic percentage change in immunization coverage.

| Country | First year | Last year | % immunized: first year | % immunized: last year | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mali | 1995 | 2006 | 38% | 68% | 30% |

| Ghana | 1993 | 2008 | 62% | 89% | 26% |

| Senegal | 1992 | 2005 | 59% | 78% | 20% |

| Niger | 1992 | 2006 | 20% | 39% | 19% |

| Cameroon | 1991 | 2004 | 47% | 65% | 18% |

| Burkina Faso | 1993 | 2003 | 41% | 57% | 16% |

| Namibia | 1992 | 2006 | 70% | 83% | 14% |

| Mozambique | 1997 | 2003 | 60% | 72% | 12% |

| Madagascar | 1992 | 2003 | 54% | 61% | 8% |

| Tanzania | 1992 | 2004 | 80% | 86% | 6% |

| Zambia | 1992 | 2007 | 77% | 80% | 3% |

| Nigeria | 1990 | 2008 | 33% | 35% | 3% |

| Chad | 1996 | 2004 | 20% | 20% | 1% |

| Benin | 1996 | 2006 | 67% | 67% | 0% |

| Rwanda | 1992 | 2005 | 91% | 87% | -4% |

| Malawi | 1992 | 2004 | 89% | 82% | -7% |

| Kenya | 1993 | 2003 | 87% | 72% | -15% |

| Zimbabwe | 1994 | 2005 | 85% | 62% | -23% |

This table provides information at a country level rather than province level, and variation within countries could be significant. There does not appear to be strong evidence of a continent-wide positive trend in immunization rates, but it does not appear, on its own, to rule out the idea that the observed change in Cabo Delgado purely reflected a broader (country-wide or continent-wide) change. We note, however, that Cabo Delgado's 2003 coverage rate was slightly below the Mozambique overall rate, while its post-project rate was above the Mozambique overall rate (and above every other country's overall rate).

Bottom line on the Cabo Delgado program between 2001-2008

We do not feel that any of the pieces of evidence above is highly compelling by itself. But we are persuaded of VillageReach's impact by the combination of the observations that VillageReach's program (a) entered an area with clearly documented logistics problems; (b) reduced stockouts - one of the clearest measures of the logistics improvement it was aiming for - to near-zero levels; (c) brought Cabo Delgado from an "average" (for the country) level of coverage to an extremely high level of coverage; (d) was reported not to have been supplemented by other nonprofits' programs.

Can improvements be maintained?

Based on the evidence above, we feel that the VillageReach program has improved capacity to deliver vaccines in Cabo Delgado. However, the Cabo Delgado project officially became the local government's responsibility in 2007,41 and a recent report states, "The data suggests that following the discontinuation of field coordinator teams delivering supplies and performing supervision, the districts and health centers are having difficulty reliably picking up supplies, stock-outs of vaccines are beginning to occur again, there is some (not statistically significant) evidence that immunization coverage is beginning to fall, and district level budgets are not being maintained for these activities."42 (Emphasis ours.) VillageReach's representatives have stated to us that the government has been "slid[ing] back into the old collection-based system."43

The fact that VillageReach is monitoring the program's continuing performance, and being open about setbacks, is encouraging; but news of program deterioration is cause for concern. As discussed above, VillageReach is now planning to reactivate its support role in Cabo Delgado while continuing to push for the government to adopt its model.

Ultimately, we are skeptical about VillageReach's ambitions of handing over its model to the government. However, we note that VillageReach could be making lasting differences in individuals' lives even if its effects on health care are only temporary, since 1-3 doses of most vaccines are sufficient to immunize children against diseases. (Details here.) Our recommendation of VillageReach is made under the assumption that it will not succeed in getting its model adopted by the government, while recognizing that its ultimate cost-effectiveness would be much higher if it could.

Nampula activities

As described above, VillageReach briefly worked in the Nampula province of Mozambique before handing its activities off to a local organization in January 2007.

VillageReach provided us with internally collected data from this project through August 2008, and stated to us that the data became unreliable (due to internal contradictions) after that point. We have not yet received clearance to post the data publicly. Overall, it showed encouraging trends that resemble the trends outlined above: increasing numbers of immunizations and substantial drops in the rates of stockouts and other logistical problems. However, because of the fact that the data terminates at an apparently arbitrary point, we have serious doubts about the impact of this project.

This project's expenses, overall, were equal to about 20% of the expenses associated with the pilot project (details in our cost-effectiveness section). VillageReach representatives have stated to us that the very limited role VillageReach took is not representative of VillageReach's typical or future activities.

Possible negative/offseting impact

As stated here, we are generally concerned about charities' potential diversion of skilled labor and/or interference with government responsibilities. However, we believe these concerns are smaller with VillageReach than with other charities we've seen.

VillageReach's focus is on improving logistics rather than on increasing the available resources in an area. Its cost analysis argues that its program ultimately ends up saving the government money (more below), and a conversation with its representatives implies that it does not attempt to repurpose skilled labor from other areas or sectors.44 In addition, it appears to be seriously committed to handing off its programs to the government over time, as it has done in Cabo Delgado. It does not appear to grant funds directly to governments.

What can be expected of future activities?

We feel that the planned Mozambique activities are highly similar to the pilot project analyzed above - and will be evaluated with a similar level of rigor. Because there has only been one demonstrated success, these activities should be considered to have a reasonable risk of failure, but they are - to us - clearly good investments because they are highly similar to activities that have worked before, and we believe VillageReach has made a credible commitment to continue documenting their success or failure.

We are less positive on VillageReach's contract engagements, many of which we have very little information about. The South Africa project that VillageReach must raise $100,000 in "matching donations" for is particularly worrisome to us, as we find the proposal for activities and impact assessment relatively vague.

What do you get for your dollar?

Past cost-effectiveness: pilot program

We do not attempt to quantify the full benefits of the VillageReach program. Instead, we observe that even a relatively conservative estimate of its cost per child vaccinated would imply quite strong cost-effectiveness (in terms of cost per death averted).

The Disease Control Priorites report (Jamison et al. 2006) estimates the cost per fully-immunized child with a basic set of vaccines at $14.21 in sub-Saharan Africa.45 According to Jamison et al. (2006), this implies a cost per death averted of approximately $200.46

- VillageReach's estimate: VillageReach sent us a draft of its internal review of the Cabo Delgado project's cost-effectiveness. VillageReach estimates that its program is significantly more cost-effective than the government's program, at a cost of $5.76 per child receiving three doses of each DTP and hepatitis B vaccines (which VillageReach asserts is a proxy for a fully immunized child), including both VillageReach and government costs.47 This would imply a cost-per-death averted that is significantly lower than the DCP's estimate of $200, and thus easily within the range we consider highly cost-effective (discussed here).

- GiveWell's conservative estimate: We assumed that all VillageReach costs are attributable to the Cabo Delgado project (including costs associated with Nampula activities, due to our uncertainty about these activities' impact), and that there is no impact of VillageReach on immunization coverage beyond 2008 (the last year for which we have data). We also assumed that starting in 2003, the difference in immunization coverage between Cabo Delgado and Niassa can be attributed to VillageReach's program. These assumptions yield an estimate of one additional child fully immunized for every ~$41 of VillageReach's expenses.48 If the Disease Control Priorities Report is correct to estimate that $15 per fully immunized child corresponds to $200 per death averted, this would imply that VillageReach is averting a child death for every ~$545 it spends, still well within the range discussed on our overview of cost-effectiveness estimates. (This estimate ignores government costs entirely, in order to give a sense of what is accomplished for donor money.)49

Cost-effectiveness of future activities?

We feel that the planned Mozambique activities are highly similar to the pilot project analyzed above. However, we have little idea of what to expect from the contract engagements - most importantly, the South Africa project for which VillageReach must raise $100,000 over 3 years in "matching donations."

To be conservative, we assume that the South Africa project and VillageReach's "development" projects will have zero impact - in other words, that VillageReach's full operating expenses, minus the funds coming from contract engagements, are the full costs of its Mozambique activities. Doing so implies total costs of around $1.6 million per year (see above). The pilot project spent around $4 million over 6 years, or around $650,000 per year; the projected total organizational expenses are $1.6 million for the next year, or ~2.5 times as much. Mozambique activities will be larger-scale than previous activities, with estimated vaccinations of 71,640 in the next year and presumably more in future years.50 This implies that the scale exceeds the pilot project's by at least 15%.51

If we conservatively assume ~2.5x as much expenses as the pilot project with ~15% more impact, applying the multiple to our conservative estimate from above would yield around $1150 per life saved.

Because this estimate makes so many conservative assumptions, we feel it is overall reasonable to expect future activities to result in lives saved for under $1000 each.

Room for more funds?

Because VillageReach is a small organization with a constantly changing funding situation, its budget is generally in flux. Our latest update, in mid-December 2009, assembles the picture as follows:52

| Program | Earmarked revenue | Projected expenses | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mozambique activities | $292,784 | $738,775 | $445,991 |

| South Africa matching requirement | N/A | $33,333 | $33,333 |

| Misc | $124,532 | $181,218 | $56,686 |

| Prog Development | $14,947 | $86,944 | $71,997 |

| IT Development | $9,258 | $140,886 | $131,628 |

| VidaGas | $8,260 | $55,460 | $47,200 |

| Other Social Enterprise | $147,237 | $131,887 | -$15,350 |

| Social Enterprise Development | $9,827 | $82,603 | $72,776 |

| General operating | $658,438 | $143,312 | -$515,126 |

| Total | $1,265,283 | $1,594,418 | $329,135 |

Bottom line:

- Donations will be used first to fund matching requirements for the South Africa program, then to fund the planned Mozambique activities and associated operating expenses, then to fund new program development and social enterprise support.

- The total funding gap is $329,135 for the next year. If revenue exceeds this amount, the most likely short-term use will be ensuring that VillageReach can complete all three years of its planned Mozambique activities, approximately $1.2 million over 3 years.53 Funds beyond that point would be used to expand further in Mozambique, at a cost of about $1 million per year per province.

- We feel that VillageReach could productively absorb up to around $2.5 million in additional funding over the next year. This would ensure that it could meet its current needs, complete its planned Mozambique activities, and begin (i.e., pay for one year of) expanded activity in Mozambique.

Financials/other

All data comes from VillageReach's IRS form 990s for 2002-2007, 54

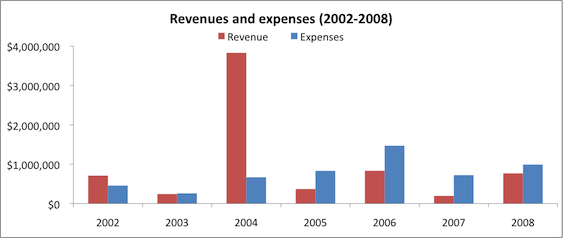

Revenue and expense growth (about this metric): VillageReach reached a large five-year, $3.3 million grant agreement with the Gates Foundation in 2004,55 which explains the large jump reported revenues in 2004.56

In 2007, both revenues and expenses fell. It's possible that this is because VillageReach had completed its work in Mozambique and was largely focused on reviewing and evaluating that project.

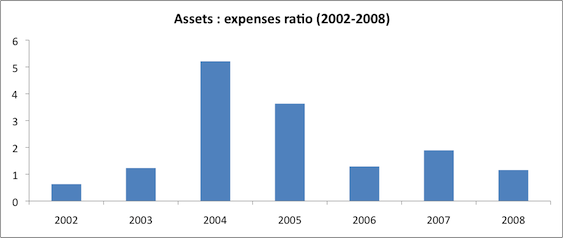

Assets-to-expenses ratio (about this metric): VillageReach has maintained an assets:expenses ratio of between approximately 1:1 and 2:1, aside from the year (and year after) they received the Gates Foundation grant.

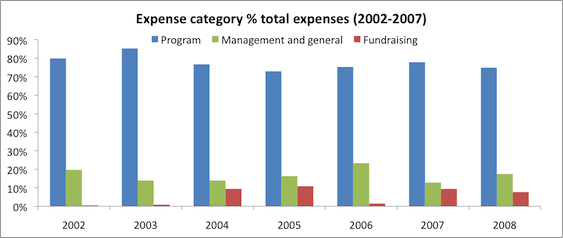

Expenses by program area (about this metric): See discussion above.

Expenses by IRS-reported category (about this metric): VillageReach maintains a reasonable "overhead ratio", spending approximately 70-80% of its budget on program expenses.

Sources

- Barrett, Leah. VillageReach Program Manager. Email exchange with GiveWell (PDF), June, 2009.

- Beale, John, Allen Wilcox, and Becca Miller. VillageReach Director of Strategic Development, President, and Finance and Program Administration Manager. Phone conversation with GiveWell, May 21, 2009.

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. VillageReach. http://www.gatesfoundation.org/Grants-2004/Pages/VillageReach-OPP30874… (accessed April 26, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5pHHJonys.

- GiveWell. VillageReach funding gap analysis-December 2009 (XLS).

- Jamison, Dean T., et al., eds. 2006. Disease control priorities in developing countries (PDF). 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Kane, Mark. 2008. Evaluation of the Project to Support PAV (Expanded Program on Immunization) In Northern Mozambique, 2001-2008: An Independent Review for VillageReach With Program and Policy Recommendations (PDF). Seattle: VillageReach.

- Leach-Kemon, Katie, Mariana DionÃsio, and Nelia Taimo. 2008. Evaluation of the Project to Support PAV (Expanded Program on Immunization) in northern Mozambique, 2001-2008: Statistical analysis (PDF). Seattle: VillageReach.

- Miller, Becca. VillageReach Finance and Program Administration Manager. E-mail exchange with GiveWell, December 23, 2009.

- Miller, Becca. VillageReach Finance and Program Administration Manager. E-mail to GiveWell (DOC), December 18, 2009.

- Measure DHS. Statcompiler. http://www.statcompiler.com (June 30, 2009). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5pHHJ86G9.

- VillageReach. 2010 budget (PDF).

- VillageReach. Comparison of costs incurred in dedicated and diffused vaccination logistics systems: Cost-effectiveness of vaccine logistics in Cabo Delgado and Niassa provinces, Mozambique. Summary available (PDF). VillageReach has asked us not to post the full text online.

- VillageReach. Cost Estimates, 8/17/09 (XLS).

- VillageReach. Expansion graph (PPT).

- VillageReach. Five year project report (PDF).

- VillageReach. Funding gap memo (PDF).

- VillageReach. IRS Form 990:

- VillageReach. John Snow proposal. Currently withheld due to confidentiality request due to discussion of pending contracts. Interested individuals should contact VillageReach.

- VillageReach. Medicines for Malaria Ventures proposal. Currently withheld due to confidentiality request due to discussion of pending contracts. Interested individuals should contact VillageReach.

- VillageReach. Milestones (PDF).

- VillageReach. Mission report - VillageReach: Logistics support to health services - MISAU Mozambique (PDF).

- VillageReach. Nigeria budget. Currently withheld due to confidentiality request due to discussion of pending contracts. Interested individuals should contact VillageReach.

- VillageReach. President's report, September 12, 2009. Currently withheld due to confidentiality request due to discussion of pending contracts. Interested individuals should contact VillageReach.

- VillageReach. South Africa proposal. Currently withheld due to confidentiality request due to discussion of pending contracts. Interested individuals should contact VillageReach.

- VillageReach. Website:

- VillageReach. About VillageReach. http://villagereach.org/about-us/about-villagereach/ (accessed April 23, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5pCYUtlLc.

- VillageReach. Board of Directors and Advisors. http://villagereach.net/about-us/board-of-directors-advisors/ (accessed April 23, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5pDGzQgrO.

- VillageReach. Field programs. http://villagereach.org/what-we-do/field-programs/ (accessed May 14, 2010).

- VillageReach. Northern Mozambique project. http://web.archive.org/web/20080726084956/http://www.villagereach.org/M… (accessed January 11, 2010).

- VillageReach. Supply chain. http://web.archive.org/web/20080630001351/www.villagereach.org/supply_c… (accessed January 11, 2010).

- Wilcox, Allen, and Becca Miller. VillageReach President, and Finance and Program Administration Manager. Phone conversation with GiveWell, November 10, 2009.

- World Health Organization. Glossary. http://www.who.int/immunization_monitoring/glossary/en/index.html (accessed April 23, 2010). Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5pDJPLQ56.

- 1

"For nearly ten years, VillageReach's health systems strengthening programs have maintained a clear focus on the last mile healthcare access. Our approach focuses on the logistics of medical supply and service delivery to increase reliable access to healthcare in the poorest, most remote locations." VillageReach, "About VillageReach."

- 2

"VillageReach was founded in Seattle, Washington in 2000 by Blaise Judja-Sato." VillageReach, "About VillageReach."

- 3

Kane 2008, Pg 10.

- 4

"We have transitioned the VillageReach model and program to the local Ministry of Health in Cabo Delgado province, home to 88 vaccination clinics. VillageReach and FDC, our local implementation partner, will continue to provide technical assistance and data reporting." VillageReach, "Milestones."

- 5

VillageReach, "Northern Mozambique Project."

- 6

- "The Project has already been replicated in Nampula, where it is currently being implemented by the FDC." Kane 2008, Pg 8.

- "August 2006: Began deliveries in 85 health centers (in North and Central zones in12 districts) in Nampula." Kane 2008, Pg 16.

- 7

"We officially transitioned Nampula province to FDC in January 2007, and they officially ended the project in August 2009- which means the technical assistance and support ended but the Ministry continues to do the activities." Becca Miller, e-mail to GiveWell, December 18, 2009.

- 8

VillageReach, "Funding Gap Memo," Pg 1.

- 9

"VR recommends a plan including a province level baseline and end line in Cabo Delgado, Niassa and a third comparison province. We have included the full range of monitoring & evaluation options in the table below to show how and why we prefer this option. This preferred plan is included as option number 8 in the table below and is the basic assumption in all funding gap projections." VillageReach 2009, "Funding Gap Memo," Pg 2.

- 10

VillageReach, "Funding Gap Memo," Pg 3.

- 11

VillageReach, "Expansion Graph."

- 12

VillageReach, "South Africa Proposal," Pg 4.

- 13

VillageReach, "South Africa Proposal," Pg 7.

- 14

VillageReach, "South Africa Proposal," Pg 12.

- 15

VillageReach, "South Africa Proposal," Pg 7.

- 16

Allen Wilcox and Becca Miller, phone call with GiveWell, November 10, 2009.

- 17

"This report was compiled by Mark Kane, MD, MPH, a consultant, following review of these materials and extensive discussions with VillageReach staff. Many of the opinions and viewpoints in this report are those of the reviewer, and do not necessarily represent the views of the VR, its staff, or Project implementation partners." Kane 2008, Pg 12. Dr. Kane is listed on VillageReach's Board of Advisors, see VillageReach, "Board of Directors and Advisors."

- 18

"Under the previous system of distribution, clinic workers in need of vaccines and other medical supplies were required to travel many miles, often on foot, to a provincial or district warehouse to obtain supplies that were not always available. Today, in Cabo Delgado, health workers at 90 rural clinics receive monthly deliveries from one of VillageReach's three delivery trucks, specially outfitted to navigate the difficult terrain of rarely maintained roads and sustain the cold chain necessary for the safe transport of vaccines. As the VillageReach drivers leave from the provincial warehouse for two-week excursions, they bring with them the necessary vaccines, medical supplies, and energy needed by each clinic to serve their communities." VillageReach, "Supply Chain."

- 19

Kane 2008, Pgs 17-18.

- 20

World Health Organization, "Glossary."

- 21

Kane 2008, Pg 10.

- 22

Kane 2008, Pgs 19-20.

- 23

Kane 2008, Pg 24.

- 24

Kane 2008, Pg 14

- 25

VillageReach, "Mission Report - VillageReach: Logistics Support to Health Services - MISAU Mozambique."

- 26

VillageReach, "Mission Report - VillageReach: Logistics Support to Health Services - MISAU Mozambique," Pg 9, Table 1.1.

- 27

VillageReach, "Mission Report - VillageReach: Logistics Support to Health Services - MISAU Mozambique," Pg 10, Table 2.1.

- 28

VillageReach, "Mission Report - VillageReach: Logistics Support to Health Services - MISAU Mozambique," Pg 10, Table 2.2.

- 29

"Comparison data was obtained from a 2007 immunization coverage cluster survey conducted by DPS in the neighboring province of Niassa, in which the Project did not operate." Kane 2008, Pg 6.

- 30

"This study used data from the 2003 Mozambique Demographic and Health Survey (DHS 2003) as baseline data. DHS surveys are cross-sectional household surveys that are representative on both a national and provincial level...12,315 households were included in the study...The variable 'DTP 3' was computed using the following variables from the Mozambique DHS 2003 dataset: 'received DTP 1,' 'received DTP 2,' and 'received DTP 3.' 'DTP 3' was defined as those children who received all DTP doses (DTP 1-3) according to card or history." Leach-Kemon, DionÃsio, and Taimo 2008, Pg 9.

- 31

Leach-Kemon, DionÃsio, and Taimo 2008, Pg 10.

- 32

Leach-Kemon, DionÃsio, and Taimo 2008, Pg 16.

- 33

Kane 2008, Pg 23.

- 34

Leah Barrett, e-mail exchange with GiveWell, June, 2009.

- 35

"The Statistical Analysis for the quantitative surveys carefully describes the factors that could bias the evaluation results:

- Baseline surveys were not done at the inception of the project

- A “comparison” Province (or Provinces) was not designated at the initiation of the project

- Comparing the results of surveys done with different methodologies (DHS and EPI cluster surveys) creates certain potential biases

- Relatively small sample sizes made it difficult to detect small changes in coverage between the two age groups

- Uncertainty about the reasons districts were chosen for the Niassa survey

- Uncertainty about the comparability of Niassa as a “comparison” province."

Kane 2008, Pg 23.

- 36

Kane 2008, Pg 24.

- 37

Kane 2008, Pg 24

- 38

"You are right that a lot happened in Cabo Delgado between 1997-2001 and the coverage rates reflect that. Cabo Delgado was particularly hard hit by Mozambique's civil war from 1977-1992, which the health system in a very poor state and landmines prevented people from traveling to the facilities that did exist. In 1994, Mozambique had their first multi-party elections and major rehabilitation efforts followed. In the 1997-2001 time period, there was a lot of effort put into building new health centers in Cabo Delgado, which greatly increased access to immunization services in the province." Leah Barrett, e-mail exchange with GiveWell, June, 2009.

- 39

Measure DHS, "Statcompiler." We accessed data through the StatCompiler tool and looked at all available surveys for Sub-Saharan Africa.

- 40

We downloaded data on DTP-3 immunizations. The percentages in the table reflect reports either from (a) the child's vaccination card or (b) a mother's report (called "either source" in the Measure DHS tables). We only include countries that had at least one survey during or before 1997 and at least one survey during or after 2003; 1997-2003 was the period over which VillageReach provided Measure DHS surveys for Cabo Delgado.

"We have transitioned the VillageReach model and program to the local Ministry of Health in Cabo Delgado province, home to 88 vaccination clinics. VillageReach and FDC, our local implementation partner, will continue to provide technical assistance and data reporting." VillageReach, "Milestones."

Kane 2008, Pg 26.

"When we turned it over to the government they let it slide back into the old collection-based system. That's what led to the minister and the government said this system works and we should implement it nationwide. The government did recognize that the newer system is better and decided to reverse going back to the old system." John Beale, Allen Wilcox, and Becca Miller, phone conversation with GiveWell, May 21, 2009.

"The people that we hired initially were retired MOH employees; in Nampula they remained MOH employees and were just under our management for a period of time." John Beale, Allen Wilcox, and Becca Miller, phone conversation with GiveWell, May 21, 2009.

Jamison et al. 2006, Pg 401. For more, see our discussion of the cost-effectiveness of immunization programs.

Jamison et al. 2006, Pg 401. For more, see our discussion of the cost-effectiveness of immunization programs.

VillageReach, "Comparison of Costs Incurred in Dedicated and Diffused Vaccine Logistics Systems."

For Cabo Delgado, we have (a) the number of children receiving 3 doses of DTP (which Kane 2008, following GAVI, asserts is a proxy for "fully immunized") in 2001-2007 (Kane 2008, Pg 19) and (b) the percentage of children immunized in 2003 and 2008 (Kane 2008, Pg 23). For Niassa, we have the percentage of children immunized in 2003 and 2008 (Kane 2008, Pg 23).

The use of DTP-3 as a proxy for full immunization is supported by data from Cabo Delgado (reported by Leach-Kemon, DionÃsio, and Taimo 2008, Pg 63, Table 1-11). Coverage rates of BCG, polio 3, and measles vaccinations were at least as high as DTP-3 coverage. In addition, 92.8% of children in the 24-35 months age group were "fully-vaccinated," while 95.4% were immunized with DTP-3.

We credit VillageReach with each child immunized in Cabo Delgado above and beyond the percentage immunized in Niassa for the same year, starting in 2003 (the year after the VillageReach program began), interpolating data (linearly) when it is missing. While far from ideal, we find this a reasonably appropriate comparison, as we estimate the Cabo Delgado coverage rate prior to VillageReach's involvement to have been close to the Niassa coverage rate (see Leah Barrett, email exchange with GiveWell, June, 2009).

| Year | CD: # of children vaccinated | CD: % of children immunized | Niassa: % of children immunized | Children in Cabo Delgado needing immunizations | Calculated: Additional children immunized in CD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 50,588 | 69% | 55% | 73,316 | 10,264 |

| 2004 | 54,584 | 76% | 58% | 72,297 | 12,652 |

| 2005 | 58,861 | 82% | 61% | 71,782 | 15,074 |

| 2006 | 64,772 | 89% | 64% | 73,189 | 17,931 |

| 2007 | 71,044 | 95% | 67% | 74,783 | 20,939 |

| 2008 | 71,250 | 95% | 70% | 75,000 | 18,750 |

- Immunization rates: Evidence suggests that immunization rates fell slightly between 2007-2008 as VillageReach handed over responsibility for the program (see the Can Improvements be Maintained section on this page). We don't know how much rates fell, so to err on the conservative side, we assign the same rate to 2007 that is assigned to 2008. We linearly interpolate the immunization rate between 2003-2007 (in Cabo Delgado) and 2003-2008 (in Niassa).

- Children in need of vaccination: Calculated as follows: (# of children immunized in Cabo Delgado) / (% of children immunized in Cabo Delgado).

- Addtional children immunized: Calculated as follows: [(% of children immunized in Cabo Delgado) - (% of children immunized in Niassa)] * (Total number of children in need of immunizations in Cabo Delgado).

Our total impact estimate comes to 95,610 additional children immunized (we do not apply a discount rate; a moderate discount rate would make little difference due to the short time period under discussion).

Costs are detailed in VillageReach, "Cost Estimates, 8/17/09." We include all costs, even those allocated to the Nampula activities, for which we assume no impact. Between 2001 and 2006 (the year VillageReach stopped financially supporting the program in Cabo Delgado), VillageReach spent a total of $3,910,411, implying (with the impact estimate above) $40.90 spent by VillageReach for every additional child immunized between 2003-2008.

If one assumes that the government spends an additional $15 per child - consistent with the Jamison et al. (2006) estimate of the costs for a standard expansion program, and probably an overstatement (since some of VillageReach's costs likely substitute for government costs) - the implied total cost per death averted rises to ~$745, still well within the range discussed on our overview of cost-effectiveness estimates.

VillageReach 2009, "Expansion graph," slide 1. More vaccinations are projected in future years, but this is under the assumption that VillageReach expands further into the Tete province - we find it likely but not a given that vaccinations are also projected to rise even if expansion into Tete does not happen.

See our table of immunizations for the pilot project (in footnote 53 above), which averaged 61,850 per year. 71,640 (next year's projection) is about 15% greater than 61,850.

Sources:

- VillageReach, "2010 Budget."

- John Beale, email to GiveWell, December 21, 2009.

- Becca Miller, email to GiveWell, December 23, 2009.

- Allen Wilcox and Becca Miller, phone call with GiveWell, November 10, 2009.

- VillageReach, "President's Report, September 12, 2009."

- VillageReach, "Funding Gap Memo."

- VillageReach, "South Africa Proposal."

Details and calculations in GiveWell, "VillageReach Funding Gap Analysis-December 2009."

VillageReach 2009, "Funding Gap Memo."

VillageReach, "IRS Form 990," 2002-2007. These forms are also available for download through the National Center for Charitable Statistics at http://nccsdataweb.urban.org/PubApps/showVals.php?ft=bmf&ein=912083484 (accessed May 3, 2010).

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, "VillageReach."

Organizations report income on their tax forms in the year a grant agreement is reached. VillageReach received funds from this grant over the five-year period.