VillageReach

A note on this page's publication date

The content on this page has not been recently updated. This content is likely to be no longer fully accurate, both with respect to the research it presents and with respect to what it implies about our views and positions. Note that we are no longer updating reviews of individual organizations outside our Top Charities.

VillageReach (www.villagereach.org) was our top-rated organization for 2009, 2010 and much of 2011 and it has received over $2 million due to GiveWell's recommendation. In late 2011, we removed VillageReach from our top-rated list because we felt its project had limited room for more funding. As of November 2012, we believe that that this project may have room for more funding, but we still prefer our current highest-rated charities above it.

Published: June 2013

Summary

VillageReach (www.villagereach.org) aims to improve the systems that distribute medical supplies to rural areas in Africa, so that life-saving supplies get to those who need them. Its programs include both technical support staff and changes in logistical setups (such as moving from a system in which health clinics collect their own supplies to a centralized delivery system).

Our research on VillageReach has focused on its Dedicated Logistics System (DLS) program in Mozambique (reasons for this discussed below). It ran a pilot of this program in a single province in Mozambique from 2004 to 2007 and began, in 2010, to scale up the project to additional provinces in Mozambique. The evaluation of the pilot project was one of the best evaluations we have seen from a charity, and it provided suggestive but not conclusive evidence that the project saved lives cost-effectively. The scale-up has experienced challenges and there are indications that it will not be as effective as the pilot project. In addition, it may be more difficult to determine the impact of the scale-up project; key data that was collected for the pilot project has not been available for the scale-up project.

VillageReach has demonstrated a commitment to sharing results of its work publicly, enabling it and others to learn from both its successes and failures.

Details on VillageReach's work is also available on our VillageReach updates page, on our blog, and in our notes on our visits to VillageReach's programs inhealth Mozambique and Malawi. See also, older versions of this report.

Table of Contents

What do they do?

Broadly, VillageReach aims to improve health care access in remote, underserved places by improving the medical supply delivery systems.1 A key component of VillageReach's system focuses on shifting the distribution of health products from a "pull" system (in which health clinics collect their own supplies) to a "push" system (in which dedicated teams deliver supplies to clinics directly).2

Our research on VillageReach has focused on its work in Mozambique. Since 2009, when we first started following VillageReach's work, its Dedicated Logistics System (DLS) program in Mozambique has been the primary use of unrestricted funds (this may be changing). It implemented a pilot project in the northern Mozambican province of Cabo Delgado from 2002 to 2007 focused on delivering vaccines, and also briefly ran a similar program in the neighboring province of Nampula. It then handed off the projects. In 2010, it resumed its DLS system in Cabo Delgado, and then expanded the system to three additional provinces: Niassa, Gaza, and Maputo province.3 It has expanded the system to deliver additional supplies, particularly diagnostic tests. VillageReach's other programs have generally been fully funded by funds that a donor has restricted to a particular project, not by unrestricted funds,4 and therefore, we have not researched the details of these projects.

Pilot project in Cabo Delgado, Mozambique (2002-2007)

VillageReach, which was founded in 2000,5 conducted a demonstration of its vaccine delivery system in the province Cabo Delgado in Mozambique from April 2002 to March 2007.6 The Cabo Delgado project officially became the local government's responsibility in 2007,7 but VillageReach resumed responsibility in mid-20108 due to problems under government management.

The pilot project delivered supplies to all of the facilities in the province that offered vaccinations. In addition to vaccines, VillageReach delivered propane gas, medicines, and other medical supplies to the facilities each month.9 The components of the delivery system included:10

- Transportation vehicles: "Created multi-modal transport network including land cruisers, motorcycles and bicycles. Staff inspects and repairs equipment on monthly visits."

- Cold chain: "Introduced reliable, low maintenance and cost-effective refrigerators in clinics."

- Injection safety equipment: "Installed propane burners for sterilization, incineration points and needle removers to ensure safe disposal of used syringes."

- Supplies-tracking: "Partnered with Iridium to utilize their global satellite system, introduced communication system in trucks to enable near, real-time inventory tracking."

- Training: "Trained community representatives to provide basic health care."

- Creating a for-profit enterprise to improve energy supply: "Established VidaGas, a Mozambican propane distribution company to reliably supply energy to clinics, businesses and households."

Nampula expansion (2006-2007)

In 2006, VillageReach began to replicate the project in a second province in Mozambique, Nampula.11 It handed off the project to a local nonprofit in January 2007.12

Project scale-up in Mozambique (2010-present)

Starting in 2010, VillageReach worked to expand the model of the pilot project to other provinces in Mozambique. It originally planned to expand to eight of Mozambique's eleven provinces, but later revised it plans to four provinces. As of early 2013, its Dedicated Logistics System program was operating in Cabo Delgado, Niassa, Gaza, and Maputo provinces.13

VillageReach planned to have an active presence in each province for three years, after which point it hoped that the government health system in that province would maintain its model without further support.14 In October 2012, it updated this expectation based on its experience over the course of the scale-up, and is now less confident than it was at the start of the program that the provincial governments will maintain its program once it withdraws its support.15

In addition to vaccines and materials to support vaccination programs, the scale-up project has delivered rapid diagnostic tests for malaria and other diseases.16

For more detail on recent activities in Mozambique, see our updates on VillageReach.

Additional activities

VillageReach is also involved in other projects, specifically:

- Malawi programs. VillageReach runs three logistics programs in Malawi. We visited the first two in October 2011; the third was started more recently.17

- Kwitanda Community Health program: VillageReach seeks to strengthen health service delivery in the Kwitanda area by employing additional health workers, distributing insecticide-treated bednets, purchasing supplies for the health center, building water and sanitation infrastructure, testing patients for tuberculosis, and providing bicycles for health workers. The program is fully supported by a private donor.

- Information and communication technology for maternal and child health: The project, which is funded by a grant from Concern Worldwide, has three parts: a hotline to answer health questions from pregnant women and new mothers; text message alerts with pregnancy tips; and an appointment system for health centers to reduce waiting times.

- Pharmacy Assistants Program: The project, funded in part by the Barr Foundation, aims to "build the systems needed to support improved medicines management by training and deploying health facility-based pharmacy staff and by improving data management and reporting of logistics data across the country."18

- A variety of contract engagements. VillageReach has contracted with specific parties to carry out projects in different parts of the world, all on the theme of improving health system logistics.19

Does it work?

This section focuses on VillageReach's Dedicated Logistics System (DLS) in Mozambique. It discusses the pilot project in Cabo Delgado, its hand off of its work in Cabo Delgado to the government and in Nampula to another organization, and its scale-up to other provinces.

Pilot project in Cabo Delgado

In its evaluation of the pilot project in Cabo Delgado, VillageReach tracked the progress made in administering basic immunizations. Such immunizations are a proven, cost-effective way to improve health and save lives in the developing world (more at our report on immunization), and so success in increasing immunization coverage - alone - likely constitutes, in our view, success in saving lives.

Below we examine evidence that VillageReach's pilot project caused vaccination rates to rise in Cabo Delgado. We believe the evidence is consistant with VillageReach causing substantially improvements in the immunization rate in Cabo Delgado, but that the evidence is not conclusive.

Delivery of vaccines and medical supplies

A key component of VillageReach's model is a shift from a "collection-based" to a "delivery-based" supply system: rather than clinics' being responsible for picking up their own supplies, VillageReach's logistics team delivers supplies and provides other logistical support.20

The tables below provide data on the goods VillageReach delivered to Cabo Delgado between 2004 and 2007.21 (Note that the project began in April 2002; we aren't sure why data has not been provided pre-2004.)

| Vaccine type | August – December 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | January – April 2007 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCG | 39,000 | 129,200 | 131,260 | 43,700 | 343,160 |

| DTP-HepB22 | 37,640 | 173,310 | 171,330 | 47,020 | 429,300 |

| Polio | 87,800 | 244,480 | 303,730 | 79,020 | 715,030 |

| Measles | 19,580 | 61,210 | 77,130 | 18,390 | 176,310 |

| Tetanus | 42,630 | 182,720 | 189,230 | 61,290 | 475,870 |

| Equipment/Gas | August – December 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | January – April 2007 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syringes (0.5 ml) | 52,793 | 134,757 | 60,073 | 18,202 | 265,825 |

| Syringes (0.05 ml) | 7,769 | 25,523 | 20,570 | 7,696 | 61,558 |

| Syringes (5ml) | 991 | 15,209 | 6,684 | 2,650 | 25,534 |

| Safety boxes | 906 | 1,517 | 2,105 | 22 | 4,550 |

| Gas (in cylinders) | 485 | 2,091 | 2,286 | 692 | 5,554 |

| Gas (in Kg) | 2,668 | 11,501 | 12,573 | 3,806 | 30,548 |

Reductions in vaccine stockouts

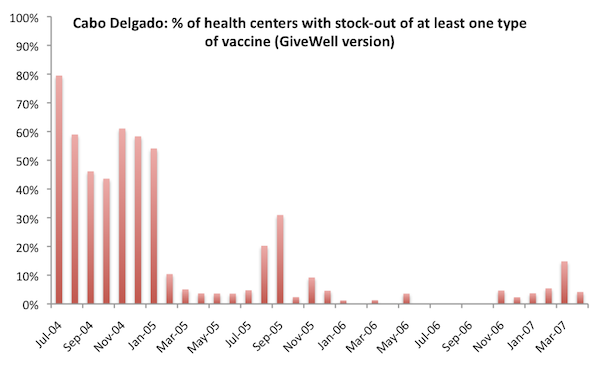

One of the key indicators that VillageReach tracked during its pilot project in Cabo Delgado was the percent of health centers that experienced a stockout of one or more vaccines in a given month. Over the course of the project the number of health centers experiencing at least one stockout fell substantially.

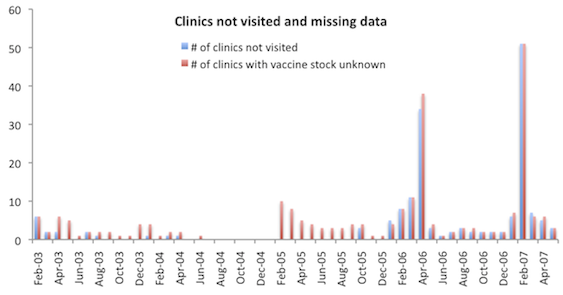

In the evaluation of its pilot project, VillageReach presents the following chart:

We have not seen the step-by-step details of how this chart was put together; however, VillageReach provided us with the data set that was used and we were able to put together a very similar chart (though not every data point matches with VillageReach's chart and we do not know what the cause of the discrepancies are):

Unless otherwise noted, all data and analysis in this section is based on the pilot project dataset VillageReach sent us. We are not cleared to share this dataset publicly. Details on the data we used to create this chart are at our report on our re-analysis of VillageReach's pilot project data.

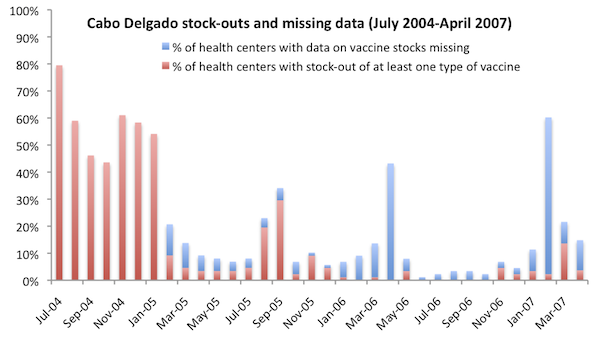

In the above chart, we excluded health centers with missing vaccine stock data from both the numerator and denominator of "% of health centers with stockout of at least one vaccine." Since stockout data was generally collected during vaccine deliveries23 and failure to visit the clinic was a primary reason for missing data,24 we would expect health centers with data missing to be more likely than other health centers to have a vaccine stockout (data was collected at the time vaccines are delivered), this assumption may show an inflated picture of VillageReach's impact. On the other hand, VillageReach told us that vaccines sometimes reached clinics without VillageReach staff visiting,25 and we note that periods of high missing data were not followed by high stockouts in the chart below, as might be expected if a missed VillageReach visit meant no vaccines reached the clinic. Below we show the percentage of health centers with data missing in each month, as well as the percentage of health centers with a stockout of at least one vaccine. The denominator in this chart includes health centers with missing data.

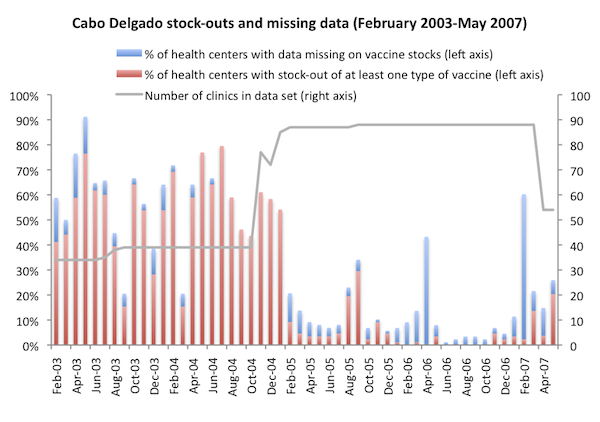

VillageReach's data set includes data from February 2003 to May 2007. The charts above, in attempting to recreate the stockout chart created by VillageReach, only cover the period July 2004 to April 2007. For greater context, we show the full date range below.

VillageReach notes that prior to mid-2004, data was not gathered with a standard form, as a result "data points gathered aren't consistent for all data points all months during that time."26 It is not clear to us what this means for stockout data specifically.

We observe from the above charts:

- Missing data was a problem throughout the project, and not accounting for missing data may result in under- or over-estimating stockouts. Because missing data indicates that the vaccine delivery team did not visit a clinic in a particular month, we would guess that stockouts were higher than average in clinics for which data is missing and thus failing to account for missing data could result in overestimating VillageReach's impact.

- Before 2005 stockout rates were on the whole, but not consistently, high in comparison with after the start of 2005. This observation supports the idea that stockouts were a common problem prior to VillageReach's intervention, but also suggests that it took a couple of years after the start of VillageReach's project for the intervention to be effective. We also note that while VillageReach describes the baseline stockout rate as "almost 80% in 2004,"27

the average stockout rate prior to February 2005 was 53% of health centers.

VillageReach notes that the program was implemented in one part of the province before expanding to the whole province, and that stockouts dropped significantly within three months of the expansion.28 The data up to October 2004 is from 34-39 clinics; the number of clinics served by the program jumped to 77 in November 2004, and then remained steady at 87-88 in January 2005 to March 2007, before dropping in April 2007 when VillageReach handed over one of three project zones to government control.29

Increases in immunization coverage in Cabo Delgado

The charts below show that (a) the number of children receiving DTP-3 (third dose of diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine30 ) immunizations increased; and (b) the number of children who "dropped out" during the DTP-3 sequence - that is, they received one, but not all doses - fell, over the course of VillageReach's pilot project, which ran from April 2002 to March 2007.31 DPT vaccination coverage is a commonly used indicator of "vaccination coverage." Charts are taken from Kane 2008.32

Were improvements attributable to VillageReach?

The evaluation of the project notes that during this time period, "Mozambique and most sub-Saharan African countries achieved significant improvements in their DTP-3 coverage, probably due to GAVI [a global funder of immunization programs] and its support for infrastructure development and provision of new vaccines and safe injection equipment."33

To evaluate the question of VillageReach's role in improvements, we look at five types of information:

- Reports from VillageReach about the problems with the immunization system in Cabo Delgado before their arrival.

- Changes in immunization coverage in Mozambique's other provinces, particularly neighboring provinces, over this period to put the observed change in context.

- Changes in immunization coverage in several countries in Africa over this period to put the observed change in context.

- Changes in immunization coverage in Cabo Delgado following the end of the pilot project.

- Alternative explanations for increasing immunization rates in Cabo Delgado over the period of the pilot project.

VillageReach reports of pre-arrival conditions: VillageReach provides a report of the obstacles to immunization coverage in Cabo Delgado before its arrival. We would prefer to have better documentation of these conditions, but nevertheless, we believe the report offers some support to the idea that VillageReach's services were needed in Cabo Delgado.

VillageReach reports,

- Intermittent closing of health facilities during business hours so health workers could pick up vaccines and supplies.

- Challenges securing transport to go to the DPS cold stores. Each district generally had one vehicle, which was for all health service trips by all health system personnel, and was also the ambulance in case of emergencies. Often, when the vehicle was needed to pick up or deliver vaccines, it was out on an emergency, in use by someone else for some other health-system function, broken down, or out of gas.

- Difficulty maintaining proper vaccine temperatures during transport.

- Uncoordinated vaccine supply requirements.

- Frequent stockouts of vaccines in health facilities.

- Funds were often liberated late – both quarterly from the provincial level to the districts, and monthly from the district administrator to the PAV Chief who needed to purchase gas for the refrigerators, fuel up the district vehicle, and pick up and distribute vaccines.34

In 2002, before starting work, VillageReach performed an assessment of access to vaccines in Cabo Delgado province.35 This report claims that, in 2002, there were 22 health facilities in the three districts in Cabo Delgado that VillageReach assessed.36 Of these 22, 4 did not offer access to vaccination services:37 two facilities because they did not have access to a cold chain; 1 because it lacked personnel; and 1 for other reasons.38

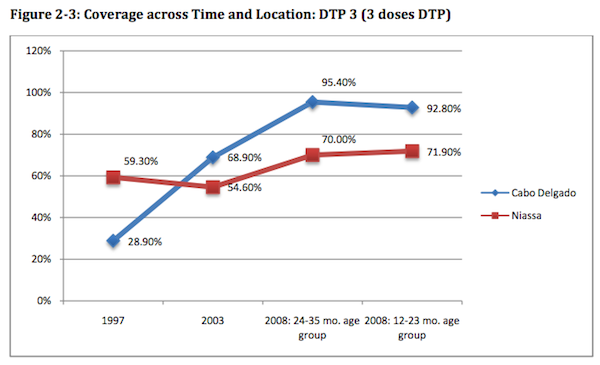

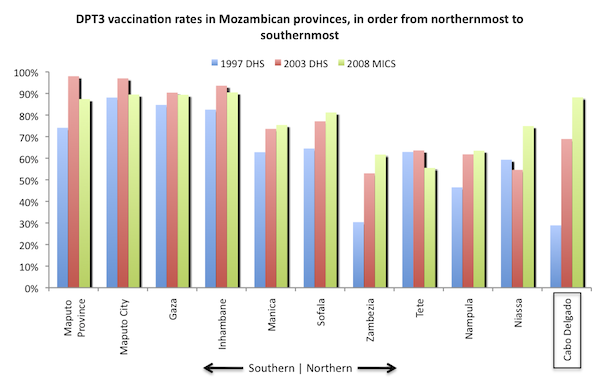

Comparing immunization coverage in Cabo Delgado to other provinces: Below we present two studies of changes in immunization coverage in Cabo Delgado compared with other provinces in Mozambique. The first was completed by VillageReach in 2008 and the second is our own analysis completed in 2012 with data that was not yet available in 2008.

VillageReach compared improvements in vaccine delivery in Cabo Delgado to improvements in the nearby Niassa province, which was not served by VillageReach.39

- Baseline data collection: Because VillageReach did not have baseline data (i.e., data from a time prior to the start of the project), it used data from the 1997 and 2003 Demographic and Health Surveys, which surveyed a large number of households and provided data on DTP-3 coverage.40

- Outcome data collection: Evaluators randomly selected households in the treatment area (Cabo Delgado province), including 474 children.41 Data from Niassa was collected by the government for reasons unrelated to VillageReach's project.42 The survey included 571 children.43

- Results: The study found that DTP-3 coverage rates increased substantially in both provinces during this period, but rates improved more in Cabo Delgado (treatment area) than Niassa (control area). The chart above shows the change in coverage rates in the two areas during this time period; the 1997 and 2003 data points are based on Demographic and Health Surveys, while the 2008 data points are from VillageReach's independent data collection (for Cabo Delgado) and a government survey (for Niassa).44

Using data from the 1997 and 2003 Demographic and Health Surveys and the 2008 Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) for Mozambique,45 we recreated the above chart and added data from other provinces for greater context. We note that VillageReach used data from its own survey for 2008 in the original evaluation, while we used survey data that was not available until 2010.46

We rely on the MICS data here because the same methods, in the same time frame, were used in both provinces. VillageReach's evaluation relied on a survey it conducted in Cabo Delgado in 2008 and a 2007 government survey from Niassa.47

We observe:

- VillageReach's evaluation report is forthright about many limitations of its comparison analysis, including limited sample size, uncertainty about the appropriateness of Niassa as a "comparison province," and issues with taking baseline and endpoint data from different sources.48

- We believe that VillageReach's chart creates an inflated picture of VillageReach's impact. We have reason to believe that there were significant improvements in immunization coverage between 1997-2001 that were more related to Cabo Delgado's recovery from the aftermath of a civil war than to VillageReach's activities.49 VillageReach's pilot project evaluation does not discuss the confounding effect of the civil war recovery.50

- The substantial increase in immunization coverage rates between 2003 and 2008 - a change seen in the neighboring province of Niassa in the MICS data (but not in the data VillageReach's evaluation used), but not in other nearby provinces - gives some reason to attribute impact to VillageReach.

- VillageReach notes that "it is ... unlikely that the activities of other NGO’s, which are not very involved in immunization activities in Cabo Delgado, were responsible for the improvement."51

Comparison of Cabo Delgado to other areas in the developing world: We took a broader look at changes in African immunization coverage over the time period in question in order to further investigate the idea that Cabo Delgado's improvements may simply have reflected a wider phenomenon. Using the Demographic and Health Surveys (Measure DHS),52 we collected data on DTP-3 immunizations for countries in Sub-Saharan Africa.53 The table below summarizes this data, sorted by the country's arithmetic percentage change in immunization coverage.

| Country | First year | Last year | % immunized: first year | % immunized: last year | Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mali | 1995 | 2006 | 38% | 68% | 30% |

| Ghana | 1993 | 2008 | 62% | 89% | 26% |

| Senegal | 1992 | 2005 | 59% | 78% | 20% |

| Niger | 1992 | 2006 | 20% | 39% | 19% |

| Cameroon | 1991 | 2004 | 47% | 65% | 18% |

| Burkina Faso | 1993 | 2003 | 41% | 57% | 16% |

| Namibia | 1992 | 2006 | 70% | 83% | 14% |

| Mozambique | 1997 | 2003 | 60% | 72% | 12% |

| Madagascar | 1992 | 2003 | 54% | 61% | 8% |

| Tanzania | 1992 | 2004 | 80% | 86% | 6% |

| Zambia | 1992 | 2007 | 77% | 80% | 3% |

| Nigeria | 1990 | 2008 | 33% | 35% | 3% |

| Chad | 1996 | 2004 | 20% | 20% | 1% |

| Benin | 1996 | 2006 | 67% | 67% | 0% |

| Rwanda | 1992 | 2005 | 91% | 87% | -4% |

| Malawi | 1992 | 2004 | 89% | 82% | -7% |

| Kenya | 1993 | 2003 | 87% | 72% | -15% |

| Zimbabwe | 1994 | 2005 | 85% | 62% | -23% |

This table provides information at a country level rather than province level, and variation within countries could be significant. There does not appear to be strong evidence of a continent-wide positive trend in immunization rates, but it does not appear, on its own, to rule out the idea that the observed change in Cabo Delgado purely reflected a broader (country-wide or continent-wide) change. We note, however, that Cabo Delgado's 2003 coverage rate was slightly below the Mozambique overall rate, while its post-project rate was above the Mozambique overall rate (and above every other country's overall rate).

Changes in immunization rates following the pilot project: VillageReach exited Cabo Delgado in 2007. Recently, two different data sets have become available on immunization coverage in the province in 2010-2011. The first is a survey conducted by VillageReach, and the second is the DHS report for 2011. The key question we asked when examining these was whether they demonstrate a worsening of immunization coverage relative to 2008; if immunization coverage had worsened in the years since VillageReach exited (during which time its distribution system was discontinued), this would provide some suggestive evidence for the importance of the VillageReach model.

The two data sets present different pictures. The VillageReach survey data shows different trends in different figures, but overall we feel it does not show worsening of immunization coverage. On the other hand, the DHS report does show signs of worsening in coverage. (Details in footnote.54 )

VillageReach notes several other factors that may have caused immunization rates to stay high in Cabo Delgado between 2007 and 2010:55

- Mozambique introduced the pentavalent vaccine in November 2009. This vaccine, which includes 5 needed vaccines in one, was accompanied by significant vaccine-related promotion activities.

- Cabo Delgado added 20 additional health centers between the end of VillageReach’s pilot project and the beginning of its scale up work. During the entire period of the pilot project, Cabo Delgado added only 1 health center.

- There were immunization campaigns in 2008 that focused specifically on measles and polio.

- FDC, the local NGO with which VillageReach partnered during the pilot project, ran a social mobilization campaign in 2008-09 in a single district of Cabo Delgado.

Alternative explanations: Alternative, non-VillageReach factors could have led to the increase in immunization. For example, in other charity examinations, there have been cases in which we noted that the charity’s entry into an area appeared to coincide with a generally higher level of interest in the charity’s sector on the part of the local government.

We have not found any evidence that activities by other NGOs (i.e., non-governmental organizations) contributed to the increase in coverage rates, but reflecting on that question led us to focus on whether activities by governmental aid organizations (multilaterals and bilaterals) could have contributed to the increase in coverage rates. To answer this question we contacted and spoke with groups familiar with Mozambique’s immunization program during the 2002-2007 period (details of research process).56

Our understanding from these conversations is that:

- As an alternative to prior separate donor-direct funding mechanisms, major international donors started contributing to “common funds” around the year 2000. Common funds aimed to provide general operating support (and greater decision making autonomy) to developing countries’ ministries of health. Provinces could chose how to allocate these funds and the government of Cabo Delgado may have allocated more resources to immunization-related activities than other provinces. Unfortunately, we have also not been able to track down data on how common funds were spent.

- In the early 2000s, other funders became interested in supporting Northern Mozambique (of which Niassa and Cabo Delgado are a part), specifically. According to USAID, Irish Aid and the World Bank provided increased support for immunization activities to Niassa during the 2000s. We have no evidence, however, of additional funders for immunization activities in Cabo Delgado.

VillageReach told us that in completing its evaluation of the pilot project, it spoke with the World Health Organization as well as with bilateral donors, and that no one had mentioned Cabo Delgado’s using common funds for immunization or additional immunization-specific funding for Cabo Delgado.57

Bottom line on the Cabo Delgado program between 2001-2008

We believe that the fall in stockouts and rise in immunization rates observed in Cabo Delgado could be attributed to VillageReach’s activities, but it is possible to speculate that the improvements in both provinces were driven by another factor that we do not have full context on. The fact that Niassa, a neighboring province, experienced a large rise in immunization rates (although not to the level seen in Cabo Delgado) over the same period (see chart above) raises the possibility (from our perspective) that non-VillageReach factors contributed to the rise in immunization rates in Cabo Delgado (although it is also possible to speculate that Irish Aid/World Bank funds spent in Niassa increased coverage rates there while the VillageReach program in Cabo Delgado was responsible for the increases in that province).

Hand off of the Mozambique projects

Cabo Delgado

The Cabo Delgado project officially became the local government's responsibility in 2007,58

and a later report stated:59

VillageReach's representatives stated to us, "When we turned it over to the government they let it slide back into the old collection-based system."60

The fact that VillageReach monitored the program's continuing performance, and has been open about setbacks, is encouraging; but news of program deterioration is cause for concern.

Ultimately, we are skeptical about VillageReach's ambitions of handing over its model to the government. However, we note that VillageReach could be making lasting differences in individuals' lives even if its effects on health care are only temporary, since 1-3 doses of most vaccines are sufficient to immunize children against diseases. (Details in our report on immunization.)

Nampula

As described above, VillageReach briefly worked in the Nampula province of Mozambique before handing its activities off to a local organization in January 2007.

VillageReach provided us with data from this project through August 2008,61 and stated to us that the data became unreliable (due to internal contradictions) after that point.62 We have not received clearance to post the data publicly. Overall, it showed encouraging trends that resemble the trends outlined above: increasing numbers of immunizations and substantial drops in the rates of stockouts and other logistical problems. However, because of the fact that the data terminates at an apparently arbitrary point, we have serious doubts about the impact of this project.

This project's expenses, overall, were equal to about 20% of the expenses associated with the pilot project. Based on multiple conversations with VillageReach representatives, it is our impression that the very limited role VillageReach took in this project is not representative of VillageReach's typical or future activities.

Project scale-up in Mozambique

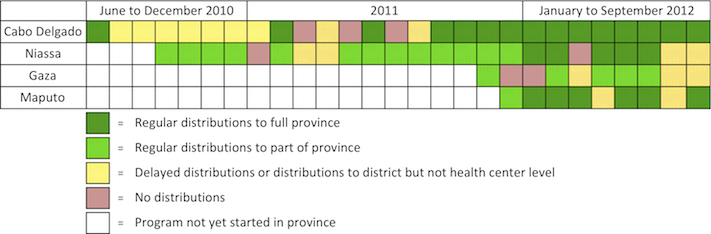

In 2010, VillageReach restarted the Dedicated Logistics System in Cabo Delgado and began discussions with other provinces to use the system to deliver vaccines and other medical supplies to health centers in those provinces. It originally planned to scale-up to eight provinces. As of early 2013, it was working in four provinces and did not have plans to expand further.63 At the time of this writing, data on changes in immunization rates were not yet available, but there are reasons to believe that the scale-up project will not be as effective as the pilot project:

- Baseline vaccination rates are higher. The four provinces that VillageReach is working with are starting at fairly high levels of vaccination coverage,64 so the scope for improvement is more limited than it was in the pilot project.

- Distributions have been somewhat irregular.65

- Global vaccine supply has experienced disruptions, leading to stockouts that VillageReach's system is unable to address. 66

We have not seen similar data on distribution regularity for the pilot project, but the fact that regular distributions did not occur in Cabo Delgado for the first ~1.5 years of the project and distributions were only to part of the province in Niassa and Gaza for most or all of the project, indicates that the project is performing below expectations. The reasons for these problems are discussed in our updates on VillageReach.

In addition, it may be more difficult to assess the impact of the scale-up project. As of early 2013, we have seen limited data on stockouts. The most complete stockout data we have seen is aggregated data on stockouts by vaccine type across the four provinces.67 This data is difficult to interpret because:

- We have not seen baseline stockout data from any province.

- The program is at different stages in each province (for example, VillageReach started work in Cabo Delgado in June 2010 and in Maputo in December 2011).

- We would prefer to review disaggregated and raw data to determine whether the results are consistent across provinces.

- We would also like to see data on "% of centers with at least one vaccine stockout," which was a key indicator in VillageReach's pilot project. This data was not included in the information VillageReach shared with us.

More details on the scale-up project are available in our updates on VillageReach.

What do you get for your dollar?

We do not have a current estimate of the cost-effectiveness of VillageReach's work. We do not believe that we have a sufficient understanding of the impact of VillageReach's Cabo Delgado pilot project, Mozambique scale-up, or other activities supported with unrestricted funding to give an estimate of cost-effectiveness. Because we do not currently rank VillageReach among our top charities, we have elected not to prioritize further work on this.

We published a cost-effectiveness estimate for VillageReach in 2009; we no longer have confidence in this estimate.

Room for more funds?

We do not have a current estimate of VillageReach's funding gap. Because we do not currently rank VillageReach among our top charities, we have elected not to fully investigate VillageReach's funding gap and cannot provide a specific estimate at this time.

Further discussion in our February 2013 update on VillageReach.

Financials/other

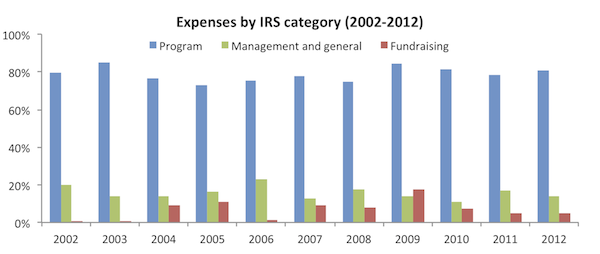

All data comes from VillageReach's IRS form 990s for 2002-2008 and its audited financial statements for 2009-2012.68

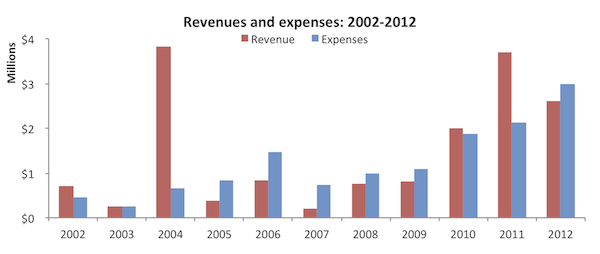

Revenue and expense growth (about this metric): VillageReach reached a large five-year, $3.3 million grant agreement with the Gates Foundation in 2004,69 which explains the large jump reported revenues in 2004.70 Both revenues and expenses have grown since a low point in 2007 (possibly due to the fact that VillageReach had completed its work in Mozambique by that time and was largely focused on reviewing and evaluating that project). Revenues were high in 2011 in a large part due to GiveWell's recommendation of VillageReach.

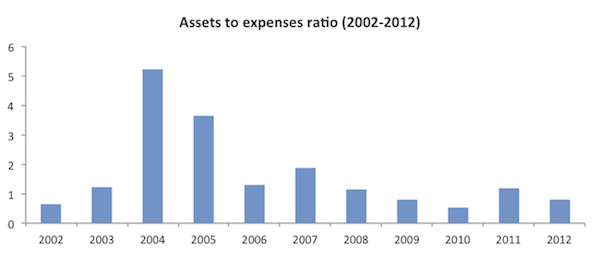

Assets-to-expenses ratio (about this metric): At the end of 2012, VillageReach had less than a years worth of expenses on hand.

Expenses by program area (about this metric): We have not sought recent information on VillageReach's program budget.

Expenses by IRS-reported category (about this metric): VillageReach maintains a reasonable "overhead ratio," spending approximately 75-85% of its budget on program expenses.

Sources

| Source name used in footnotes | Link | Date link was last accessed (for external files) | Archived link (for external files) |

|---|---|---|---|

| About VillageReach | Source | April 17, 2013 | Archive |

| Becca Miller, VillageReach Finance and Program Administration Manager, email to GiveWell, December 18, 2009 | Source | - | - |

| Gates Foundation grant to VillageReach (2004) | Source | April 17, 2013 | Archive |

| GAVI country information: Mozambique | Source | April 15, 2011 | Archive |

| GiveWell summary of regularity of distributions | Source | - | - |

| John Beale, Allen Wilcox, and Becca Miller, VillageReach Director of Strategic Development, President, and Finance and Program Administration Manager, phone conversation with GiveWell, May 21, 2009 | Unpublished | - | - |

| John Beale, VillageReach Director of Strategic Development, email to GiveWell, December 23, 2009 | Unpublished | - | - |

| John Beale, VillageReach Director of Strategic Development, email to GiveWell, September 18, 2012 | Unpublished | - | - |

| Kane 2008 | Source | - | - |

| Leach-Kemon, Dionísio, and Taimo 2008 | Source | - | - |

| Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, conversation with GiveWell, May 2, 2012 | Unpublished | - | - |

| Leah Barrett, email exchange with GiveWell, June 2009 | Source | - | - |

| Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, email to GiveWell, January 25, 2012 | Unpublished | - | - |

| Leah Hasselback, email to GiveWell, January 27, 2012 | Unpublished | - | - |

| Manuel Novela, World Health Organization EPI Specialist, Mozambique, conversation with GiveWell, March 19, 2012 | Source | - | - |

| Measure DHS Statcompiler | Source | June 30, 2009 | Archive |

| Mozambique DHS 1997 | Source | - | - |

| Mozambique DHS 2003 | Source | - | - |

| Mozambique DHS 2011 preliminary | Source | - | - |

| Mozambique MICS 2008 | Source | - | - |

| Mozambique Phase 2 Proposal to GAVI (2006) | Source | - | - |

| Mozambique vaccination data by province | Source | - | |

| Notes on site visit to VillageReach in Malawi | Source | - | - |

| Notes on site visit to VillageReach in Mozambique | Source | - | - |

| UNICEF Mozambique Immunization Plus | Source | April 15, 2011 | Archive |

| USAID Mozambique, conversation with GiveWell, April 12, 2012 | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Cabo Delgado baseline vaccination survey (2010) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Cabo Delgado logistics assessment (2002) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Cabo Delgado six-month process evaluation (February 2011) | Unpublished | - | - |

| VillageReach Field Programs | Source | July 27, 2010 | Archive |

| VillageReach financial statement (2009) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach financial statement (2010) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach financial statement (2011) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach financial statement (2012) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach IRS form 990 (2002) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach IRS form 990 (2003) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach IRS form 990 (2004) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach IRS form 990 (2005) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach IRS form 990 (2006) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach IRS form 990 (2007) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach IRS form 990 (2008) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Malawi projects | Source | April 15, 2013 | Archive |

| VillageReach Milestones | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Mozambique scale-up project overview (July 2010) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Mozambique scale-up project overview (October 2012) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Nampula Indicators | Unpublished | - | - |

| VillageReach Niassa vaccination baseline (2010) | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Northern Mozambique Project | Source | April 17, 2013 | Archive |

| VillageReach summary presentation on 2010 Cabo Delgado vaccination survey | Source | - | - |

| VillageReach Supply Chain | Source | June 2009 | Archive |

| WHO glossary | Source | April 17, 2012 | Archive |

- 1

"VillageReach improves access to healthcare for remote, underserved communities around the world...VillageReach’s model improves access to healthcare by providing a logistics platform to facilitate delivery of medical supplies and by starting and managing social businesses to improve local infrastructure." About VillageReach

- 2

"An efficient logistics system not only ensures that appropriate, high quality medicine and vaccines are available to those who need them most, but it also allows health workers to focus on provision of care for the community rather than logistics. A recent analysis of the VillageReach model in Mozambique found that in comparison to the ad hoc logistics system which is the default in most low-resource countries, VillageReach’s dedicated logistics system frees up 216 days of staff time per month, allowing for significant improvements in health worker productivity by removing unproductive time spent on vaccine logistics." VillageReach Field Programs

- 3

See our updates on VillageReach.

- 4

See discussion in our 2011 review of VillageReach.

- 5

"VillageReach was founded in Seattle, Washington in 2000 by Blaise Judja-Sato." About VillageReach

- 6

"In March 2002, a 5-year pilot project (extending from April 2002 to March 2007) was initiated. In the project, the FDC and VillageReach, in coordination with MISAU, the Expanded Program on Immunization (PAV4) and the Provincial Directorate of Health (DPS) of Cabo Delgado, distributed vaccines, gas, medicines and other essential medical supplies each month to all the heath facilities providing immunization. This included rural health facilities, which were often isolated from the normal distribution systems due to insufficient public infrastructure." Kane 2008, Pg 10.

- 7

"April 2007 - We have transitioned the VillageReach model and program to the local Ministry of Health in Cabo Delgado province, home to 88 vaccination clinics. VillageReach and FDC, our local implementation partner, will continue to provide technical assistance and data reporting." VillageReach Milestones

- 8

"The Dedicated Logistics System (DLS) was reinitiated in the province of Cabo Delgado in June 2010." VillageReach Cabo Delgado Six-Month Process Evaluation (February 2011)

- 9

"In the project, the FDC and VillageReach, in coordination with MISAU, the Expanded Program on Immunization (PAV4) and the Provincial Directorate of Health (DPS) of Cabo Delgado, distributed vaccines, gas, medicines and other essential medical supplies each month to all the heath facilities providing immunization. This included rural health facilities, which were often isolated from the normal distribution systems due to insufficient public infrastructure." Kane 2008, Pg 10.

- 10

- 11

- 12

"We officially transitioned Nampula province to FDC in January 2007, and they officially ended the project in August 2009- which means the technical assistance and support ended but the Ministry continues to do the activities." Becca Miller, VillageReach Finance and Program Administration Manager, email to GiveWell, December 18, 2009

- 13

See our February 2013 update on VillageReach.

- 14

See VillageReach Mozambique scale-up project overview (July 2010), Pg 8.

- 15

"VillageReach initially envisioned that DPS authorities in each province would effectively take over responsibility for the operation of the DLS after a period of one or two years… We are now less confident of seeing this phase realized in each of the provinces, owing primarily to the significant funding challenges, insufficient transportation available, and overloaded human resources we have seen the government experiencing." VillageReach Mozambique scale-up project overview (October 2012), Pgs 19-20.

- 16

"Specific program objectives [include] … Integrate additional key commodities – such as rapid diagnostic tests – into the dedicated logistics system." VillageReach Mozambique scale-up project overview (July 2010) Pg 7.

- 17

- 18

- 19

See discussion in our 2011 review of VillageReach.

- 20

"Under the previous system of distribution, clinic workers in need of vaccines and other medical supplies were required to travel many miles, often on foot, to a provincial or district warehouse to obtain supplies that were not always available. Today, in Cabo Delgado, health workers at 90 rural clinics receive monthly deliveries from one of VillageReach's three delivery trucks, specially outfitted to navigate the difficult terrain of rarely maintained roads and sustain the cold chain necessary for the safe transport of vaccines. As the VillageReach drivers leave from the provincial warehouse for two-week excursions, they bring with them the necessary vaccines, medical supplies, and energy needed by each clinic to serve their communities." VillageReach Supply Chain

- 21

Kane 2008, Pgs 17-18.

- 22

VillageReach reports this as "DPTHpB," however, the more common way of referring to this vaccine seems to be "DTP/HepB" or the "Tetravalent" vaccine, i.e. a combination vaccine for diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, and hepatitis B. (See UNICEF Mozambique Immunization Plus which notes, "The national EPI programme was recently bolstered by the introduction of the DPT-HepB vaccine (diptheria, pertussis, tetanus and hepatitis B)."

A proposal submitted by the government of Mozambique to the GAVI Alliance in 2006 requested the following assistance:

"Please list the vaccines to be introduced with support from the GAVI Alliance (and presentation):

1. Pentavalent vaccine – DPT/Hep B + Hib – begin introduction (national target objective of 20%), using two doses lyophilized for Hib and two doses liquid for DPT/Hep B to be used also as a diluent.

2. Continue Tetravalent – DPT/Hep B during 2007 (national target objective of 55%), using a 10 doses vial liquid for DPT/Hep B." Government of Mozambique, "Phase 2 Proposal to GAVI Alliance (2006)," Pg 18.

According to GAVI country information: Mozambique this proposal was approved for "NVS-Penta" in 2008. - 23

"In addition, VillageReach established a management information system (MIS) to track the Project’s operations and impact. The MIS tool provides reliable vaccine supply, demand and logistics information from the 'last mile' health centers. This information is collected on the monthly rounds of field coordinators." Kane 2008, Pg 11.

- 24

- 25

"When a health center is not visited, it does not mean that they don’t receive a distribution of vaccines. In most cases, the vaccines are distributed to the closest health center or the district or even to the health center itself (e.g. the road isn’t passable by vehicle but they could meet the health worker at the part of the road where it isn’t passable and distribute them there, thereby not visiting the health center and getting stock levels, but replenishing the stock). The main reason for not visiting a health center was from impassable roads. However, it is rare that a road is impassable for a long duration of time. Usually, it’s not passable when it rains but the next day or few days later, it is passable. Essentially, that means that their replenishment of vaccines happens a few days later. That increases the chances that they will have a stock out, but not so dramatically that we can reasonably assume that not visiting means a stock out." Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, email to GiveWell, January 25, 2012

- 26

Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, email to GiveWell, January 27, 2012.

- 27

"The Project to Support PAV dramatically reduced stock-outs. Regularly less than 1% of health centers reported a stock-out in 2006 compared to almost 80% in 2004." Kane 2008, Pg 7.

- 28

"It also should be noted that the distribution system was implemented in phases in the province such that it took from July 2002 – November 2004 for all of the health centers to be included in the system. During those years of 2002 – 2004, the system was being refined and tweaked to get to a point where it worked. We implemented in phases with the first 5 districts in July 2002, 2 additional districts were added, and then the remaining 10 districts in November 2004 (http://villagereach.org/vrsite/wp-content/uploads/2009/07/VillageReach_…). A phased implementation gave us time to figure out how to run the system to get the results we were after, and you can see the stock outs drop once we reached that point (just 3 months after all the districts were included in the system). This is also why we ran a 5-year pilot project, but all expansions were planned for 3 years." Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, email to GiveWell, January 25, 2012

- 29

"From April 2007, one of the three zones in the province was fully transitioned (i.e. no DLS distributions, therefore no data)." Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, email to GiveWell, January 25, 2012

- 30

- 31

Kane 2008, Pg 10.

- 32

Kane 2008, Pgs 19-20.

- 33

Kane 2008, Pg 24.

- 34

Kane 2008, Pg 14.

- 35

- 36

VillageReach Cabo Delgado logistics assessment (2002) Pg 9, Table 1.1.

- 37

VillageReach Cabo Delgado logistics assessment (2002) Pg 10, Table 2.1.

- 38

VillageReach Cabo Delgado logistics assessment (2002) Pg 10, Table 2.2.

- 39

"Comparison data was obtained from a 2007 immunization coverage cluster survey conducted by DPS in the neighboring province of Niassa, in which the Project did not operate." Kane 2008, Pg 6.

- 40

"This study used data from the 2003 Mozambique Demographic and Health Survey (DHS 2003) as baseline data. DHS surveys are cross-sectional household surveys that are representative on both a national and provincial level...12,315 households were included in the study...The variable 'DTP 3' was computed using the following variables from the Mozambique DHS 2003 dataset: 'received DTP 1,' 'received DTP 2,' and 'received DTP 3.' 'DTP 3' was defined as those children who received all DTP doses (DTP 1-3) according to card or history." Leach-Kemon, Dionísio, and Taimo 2008, Pg 9.

- 41

- 42

"As part of the evaluation, Village Reach conducted a WHO Immunization 30 x 7 Coverage Cluster Survey in Cabo Delgado in July 2008...For a 'comparison' Province they used the neighboring province of Niassa, which had data from the DHS surveys in 1997 and 2003, and from an EPI cluster survey in 2007 conducted under the auspices of DPS for reasons unrelated to this Project." Kane 2008, Pg 21.

- 43

- 44

Kane 2008, Pg 23.

- 45

Mozambique DHS 1997

Mozambique DHS 2003

Mozambique MICS 2008 - 46

Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, email to GiveWell, January 25, 2012

- 47

"As part of the evaluation, Village Reach conducted a WHO Immunization 30 x 7 Coverage Cluster Survey in Cabo Delgado in July 2008...For a 'comparison' Province they used the neighboring province of Niassa, which had data from the DHS surveys in 1997 and 2003, and from an EPI cluster survey in 2007 conducted under the auspices of DPS for reasons unrelated to this Project." Kane 2008, Pg 21.

- 48

"The Statistical Analysis for the quantitative surveys carefully describes the factors that could bias the evaluation results:

- Baseline surveys were not done at the inception of the project

- A “comparison” Province (or Provinces) was not designated at the initiation of the project

- Comparing the results of surveys done with different methodologies (DHS and EPI cluster surveys) creates certain potential biases

- Relatively small sample sizes made it difficult to detect small changes in coverage between the two age groups

- Uncertainty about the reasons districts were chosen for the Niassa survey

- Uncertainty about the comparability of Niassa as a “comparison” province."

Kane 2008, Pg 23.

- 49

- 50

"You are right that a lot happened in Cabo Delgado between 1997-2001 and the coverage rates reflect that. Cabo Delgado was particularly hard hit by Mozambique’s civil war from 1977-1992, which the health system in a very poor state and landmines prevented people from traveling to the facilities that did exist. In 1994, Mozambique had their first multi-party elections and major rehabilitation efforts followed. In the 1997-2001 time period, there was a lot of effort put into building new health centers in Cabo Delgado, which greatly increased access to immunization services in the province." Leah Barrett, email exchange with GiveWell, June 2009

- 51

Kane 2008, Pg 24.

- 52

Measure DHS Statcompiler. We accessed data through the StatCompiler tool and looked at all available surveys for Sub-Saharan Africa.

- 53

We downloaded data on DTP-3 immunizations. The percentages in the table reflect reports either from (a) the child's vaccination card or (b) a mother's report (called "either source" in the Measure DHS tables). We only include countries that had at least one survey during or before 1997 and at least one survey during or after 2003; 1997-2003 was the period over which VillageReach provided Measure DHS surveys for Cabo Delgado.

- 54

VillageReach 2010 suvery in Cabo Delgado: For the below analysis we relied on two studies conducted by VillageReach or contractors hired by VillageReach:

- Leach-Kemon, Dionísio, and Taimo 2008: A July 2008 survey of two groups of children in Cabo Delgado: children aged 12-23 months (likely vaccinated at the end and after the VR project, which ended in Feb-Apr 2007) and children aged 24-25 months (likely vaccinated during the project).

- VillageReach Cabo Delgado baseline vaccination survey (2010): An April 2010 survey of children 12-23 months of age. None of these children would have been vaccinated during the VillageReach pilot project.

There are three main indicators that VillageReach uses as numerators for the “vaccination coverage rate”:

- Fully vaccinated: child has received each of 8 vaccinations by the time of the survey (BCG, 3 x DTP, 3 x Polio, Measles). A vaccination is counted if either it is recorded on the child’s vaccination card (which are kept by parents) or if a caregiver states that the child received the vaccination.

- Fully immunized (either by time of survey or before 12 months of age): This is a stricter measure than “fully vaccinated.” In addition to having all the vaccinations, there are additional conditions which must be met:

- All vaccinations and timings must be verified on the child’s vaccination card (verbal confirmation by a caregiver is not valid).

- All 3 polio vaccinations must be received at least 28 days apart. Same for DTP vaccinations.

- Measles vaccination must be given after 9 months of age.

- DTP3: Received all 3 diptheria, pertussis, and tetanus vaccinations. Verification with the vaccination card is not needed.

In Cabo Delgado rates of “fully vaccinated” and DTP3 remained more or less constant in the 2008 and 2010 surveys:

- Fully vaccinated:

- 2008: 92.8% for 24-35 month olds and 87.8% for 12-23 months olds

- 2010: 89.1% (12-23 month olds)

- DTP3:

- 2008: 95.4% for 24-35 month olds and 92.8% for 12-23 months olds

- 2010: 91.9% (12-23 month olds)

It’s harder to interpret the fully immunized figures. The figure for this did fall between 2008 and 2010:

- Fully immunized at the time of the survey:

- 2008: 72.2% for 24-35 month olds and 73.0% for 12-23 months olds

- 2010: 57.9% or 48.8% (both numbers are given in the report; 48.8% is the one that is repeated in summary reports VillageReach has published)

- Fully immunized by 12 months of age:

- 2008: 54.9% for 24-35 month olds and 61.2% for 12-23 months olds

- 2010: 40.8%

The primary reasons that children failed to qualify as fully immunized in the 2010 survey do not appear to be issues that better vaccine logistics, the issue addressed by VillageReach’s program, would likely have addressed (these categories can overlap; from VillageReach summary presentation on 2010 Cabo Delgado vaccination survey):

- 27% of the whole sample (i.e., at least half of those who didn’t qualify as fully immunized) received their measles vaccine before 9 months of age, up from 8% in the 2008 survey

- 19% of the sample got polio or DTP shots within 28 days of each other, up from 2% in 2008 survey

- Only 11.5% of the sample got a vaccination after 12 months of age

Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) of Mozambique from 2011 (Mozambique DHS 2011 preliminary): In Mozambique vaccination data by province, we have compiled vaccination rate data from four national, high-quality surveys: 3 DHS surveys in 1997, 2003, and 2011, and a Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) from 2008. Note that only a subset of the children included in the 2008 survey were born in time to potentially directly benefit from VillageReach’s pilot project. With that caveat in mind, a few observations:- DPT3 vaccination and fully vaccinated rates observed in Cabo Delgado in 2011 were substantially lower in 2011 than in 2008, while rates were found to have risen over that period in nearby provinces, including Niassa, the comparison province from VillageReach’s project evaluation.

- Vaccination rates for vaccines earlier in the vaccination series (such as DPT1, DPT2, and BCG) were found to be about the same or decreased only slightly from the 2008 to the 2011 surveys.

- 55

Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, conversation with GiveWell, May 2, 2012

- 56

- 57

Leah Hasselback, VillageReach Program Manager, conversation with GiveWell, May 2, 2012

- 58

"We have transitioned the VillageReach model and program to the local Ministry of Health in Cabo Delgado province, home to 88 vaccination clinics. VillageReach and FDC, our local implementation partner, will continue to provide technical assistance and data reporting." VillageReach Milestones

- 59

Kane 2008, Pg 26.

- 60

- 61

- 62

- 63

"At the outset of the program in January 2010, we had expected to expand the program to eight provinces over a six-year period. However, as the program has progressed, we have determined that VillageReach funding resources for future years is likely to be less than what would be required to operate the program successfully. In addition, VillageReach has come to better understand the limited financial resources of the provincial governments it is working with. Because of periodic delays in the allocation of government funds for the DLS program – and in the absence of other 3rd-party support – VillageReach has decided to limit the program to the four provinces in which it is currently operational." VillageReach Mozambique scale-up project overview (October 2012), Pg 7.

- 64

The baseline rate of coverage for the third DPT vaccination for VillageReach's pilot project in Cabo Delgado was 68.9% (in 2003) - see above.

- Cabo Delgado: Overall immunization has fallen only slightly since the 2008 conclusion of VillageReach's work in this province. See our March 2011 update on VillageReach.

- Niassa: VillageReach's baseline report from Niassa did not include data on DPT coverage (VillageReach Niassa vaccination baseline (2010)). The 2008 DPT coverage rate in Niassa was 75% according to the Mozambique MICS 2008 and the Mozambique DHS 2011 preliminary report reported 83% coverage.

- Gaza: According to the Mozambique DHS 2011 preliminary report, 76.3% of children between the ages of 12 and 23 months have received all basic vaccinations and 89.0% have received the third DPT vaccination, a commonly used indicator of "vaccination coverage." See our February 2013 update on VillageReach.

- Maputo province: Based on the baseline study, current vaccination rates in Maputo seem extremely high - significantly above the levels VillageReach used when it estimated the impact of its program (VillageReach has not been granted permission by the government to share details publicly). See our August 2011 update on VillageReach.

- 65

- 66

“Reporting stock outs by vaccine type is more actionable data for the audience of this evaluation. Note that in the pilot project when we selected this indicator, the upstream supply of vaccines was fine but now there are problems with the upstream supply. That meant that it was a good indicator of the DLS [VillageReach’s project] performance. However, now that indicator is not a good indicator of DLS performance, but looking by vaccine type is a better indicator because we can mentally take out those vaccines with upstream supply problems.” John Beale, VillageReach Director of Strategic Development, email to GiveWell, September 18, 2012

- 67

See our February 2013 update on VillageReach.

- 68

VillageReach IRS forms for 2002-2008 and VillageReach financial statements for 2009 to 2012.

- 69

- 70

Organizations report income on their tax forms in the year a grant agreement is reached. VillageReach received funds from this grant over the five-year period.