We have published a more recent review of this organization. See our most recent report on Malaria Consortium's seasonal malaria chemoprevention program.

Malaria Consortium's seasonal malaria chemoprevention program is one of our top-rated charities and we believe that it offers donors an outstanding opportunity to accomplish good with their donations.

More information: What is our evaluation process?

Published: January 2023

Summary

What do they do? Malaria Consortium (malariaconsortium.org) works to save lives and improve health in Africa and Asia through evidence-based programs that combat targeted diseases and promote universal health coverage.1 This review focuses on its seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) program, which distributes antimalarial drugs to children 3 to 59 months old in order to prevent illness and death from malaria, typically in four or five monthly cycles during the high transmission season; our recommendation is just for this part of Malaria Consortium's work. (More)

Does it work? There is strong evidence that SMC substantially reduces cases of malaria. Malaria Consortium has conducted studies in the countries where it has worked to determine whether its programs have reached a large proportion of children targeted. Surveys conducted in 2017-21 found that on average, for children targeted to receive four cycles of SMC, 95% were covered by SMC for at least one monthly cycle, 88% for at least two cycles, 77% for at least three cycles, and 65% for all four cycles. (More)

What do you get for your dollar? We estimate that the total cost to achieve the equivalent of one person-month of SMC coverage is about $1.50. The numbers of deaths averted and other benefits of SMC are a function of a number of difficult-to-estimate factors, which we discuss below. (More)

Is there room for more funding? We conduct "room for more funding" analysis to understand what portion of Malaria Consortium's ideal future budget it will be unable to support with the funding it has or should expect to have available. We may then choose to either make or recommend grants to support those unfunded activities. Our recent analyses of Malaria Consortium's room for more funding can typically be found by visiting the "Sources" sections of our published grant pages (see a list of grant pages here). (More)

Malaria Consortium's seasonal malaria chemoprevention program is recommended because:

- SMC is a program with a strong evidence base and strong cost-effectiveness. (More)

- Track record – Malaria Consortium has experience with supporting large-scale SMC programs in seven countries and has demonstrated success at reaching a large portion of targeted children. (More)

- Room for more funding – we believe that Malaria Consortium could productively use more funding than it expects to receive to scale up its SMC activities. (More)

Table of Contents

- Summary

- Our review process

- What do they do?

- Does it work?

- What do you get for your dollar?

- Is there room for more funding?

- Malaria Consortium as an organization

- Sources

Our review process

We began speaking to Malaria Consortium about the possibility of reviewing one of its programs in January 2016.

Over the next several months we tried to determine which of Malaria Consortium's programs we should prioritize evaluating for a possible recommendation, and we ultimately settled on seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC). The other programs that we investigated included: bed nets, dengue control, injectable artesunate for severe malaria, integrated community case management (ICCM), micronutrient powders, malnutrition management, neglected tropical diseases morbidity management, integration of nutrition with SMC, prevention of malaria in pregnancy, point of care diagnosis of malaria, and diagnosis of pneumonia.

Our review process has consisted of:

- Extensive conversations with Malaria Consortium staff since 2016.2

- A conversation with a researcher at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine who has led the work on evaluating the ACCESS-SMC project, a large-scale SMC project led by Malaria Consortium.3

- Reviewing documents that Malaria Consortium shared with us.

What do they do?

Malaria Consortium works on preventing, controlling, treating, and eliminating malaria and other communicable diseases.4 It was established in 2003 and currently works in thirteen countries across Africa and Southeast Asia.5 Malaria Consortium's total spending from April 2020 to March 2021 was about $92 million, with about 94% of its spending coming from restricted funds.6

This page focuses exclusively on its seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) programs, which aim to distribute antimalarial drugs to children 3 months to 59 months old in order to prevent illness and death from malaria.7

The remainder of this section provides more detail on:

- Implementation of SMC programs

- Malaria Consortium-supported SMC programs

- Spending on SMC programs

- Malaria Consortium's role in SMC programs

Implementation of SMC programs

What are SMC programs?

As we write in our intervention report on SMC, seasonal malaria chemoprevention is the intermittent (typically monthly) administration of full courses of antimalarial drugs to children during the malaria season in areas of highly seasonal malaria transmission.8 The original WHO policy recommendation for SMC, which was released in 2012, described SMC as the administration of "a maximum of four treatment courses of SP [sulfadoxine–pyrimethamine] + AQ [amodiaquine] at monthly intervals to children aged 3–59 months in areas of highly seasonal malaria transmission"9 and where resistance to SMC drugs was low.10 In 2022, the WHO updated its policy recommendation for SMC. The key changes included dropping the requirement that SMC be delivered only in places where drug resistance is low and allowing for variability in the number of cycles delivered. As a result, SMC—which has historically only been delivered at large scale in countries in the Sahel subregion of Africa, where drug resistance is low—can now be recommended in other areas with highly seasonal malaria transmission. Countries can also decide to deliver greater or fewer cycles of SMC, in line with the length of their peak malaria transmission seasons.11

According to Malaria Consortium, "SMC is primarily delivered door-to-door by trained community distributors. A full course of SP plus AQ (SPAQ) is given over three consecutive days. On the day of the community distributor’s visit to a household, one tablet of SP and one tablet of AQ are dispersed in water and administered under the supervision of a community distributor…The remaining two doses of AQ are given to the caregiver to disperse and administer once daily over the next two days...Each full course of SPAQ confers a high degree of protection from malaria infection for approximately 28 days."12

Malaria Consortium SMC implementation methods

Malaria Consortium supports training of health facility workers and community distributors (CDs) to deliver SMC primarily by going door-to-door.13 Some CDs are community health workers (CHWs), who are people in the community who support basic delivery of health interventions. The majority of CDs are recruited and trained to only deliver SMC and do not provide any other community health services.14 Malaria Consortium told us that CDs are typically paid about $5 to $7 per day for programs such as SMC, though this amount varies by country.15 Malaria Consortium also supports training for supervisors for the program.16

In the past, Malaria Consortium has typically supported four SMC cycles. Beginning in 2021, Malaria Consortium supported the governments of Burkina Faso and Nigeria in adding a fifth cycle of SMC (in addition to the usual four) in locations that are eligible for an additional cycle because their peak malaria transmission season is longer than in other SMC-eligible locations. It also supported an implementation research study in Uganda delivering five cycles.17 Each cycle includes a four- or five-day distribution period and lasts 28 days, at which point a new cycle starts.18 For each cycle, Malaria Consortium instructs CDs to:19

- determine whether the child is eligible for SMC and give the age appropriate dose.20

- refer all acutely sick children and children with fever to the health facility or a qualified community health worker for evaluation and testing for malaria.21

- directly observe the child swallowing the first dose of dispersible SP+AQ, and then re-dose if the child vomits or spits out all of the medicine within 30 minutes of taking the first dose of the medication.22

- give the child's caregiver 2 tablets of AQ and explain how to give the doses over the following two days.23

- record all doses provided on a tally sheet and mark the wall of the household or compound as visited.24

- advise the child's caregivers to mark a card to record that they've given the other two doses,25 to give the medication again if the child vomits (and to visit the health facility to request replacement doses if this happens), and to take the child to the health facility if they get a fever or are very sick.26

- provide health promotion and malaria prevention messages, including explaining the purpose and benefit of SMC and the importance of children and pregnant women sleeping inside a bed net each night.27

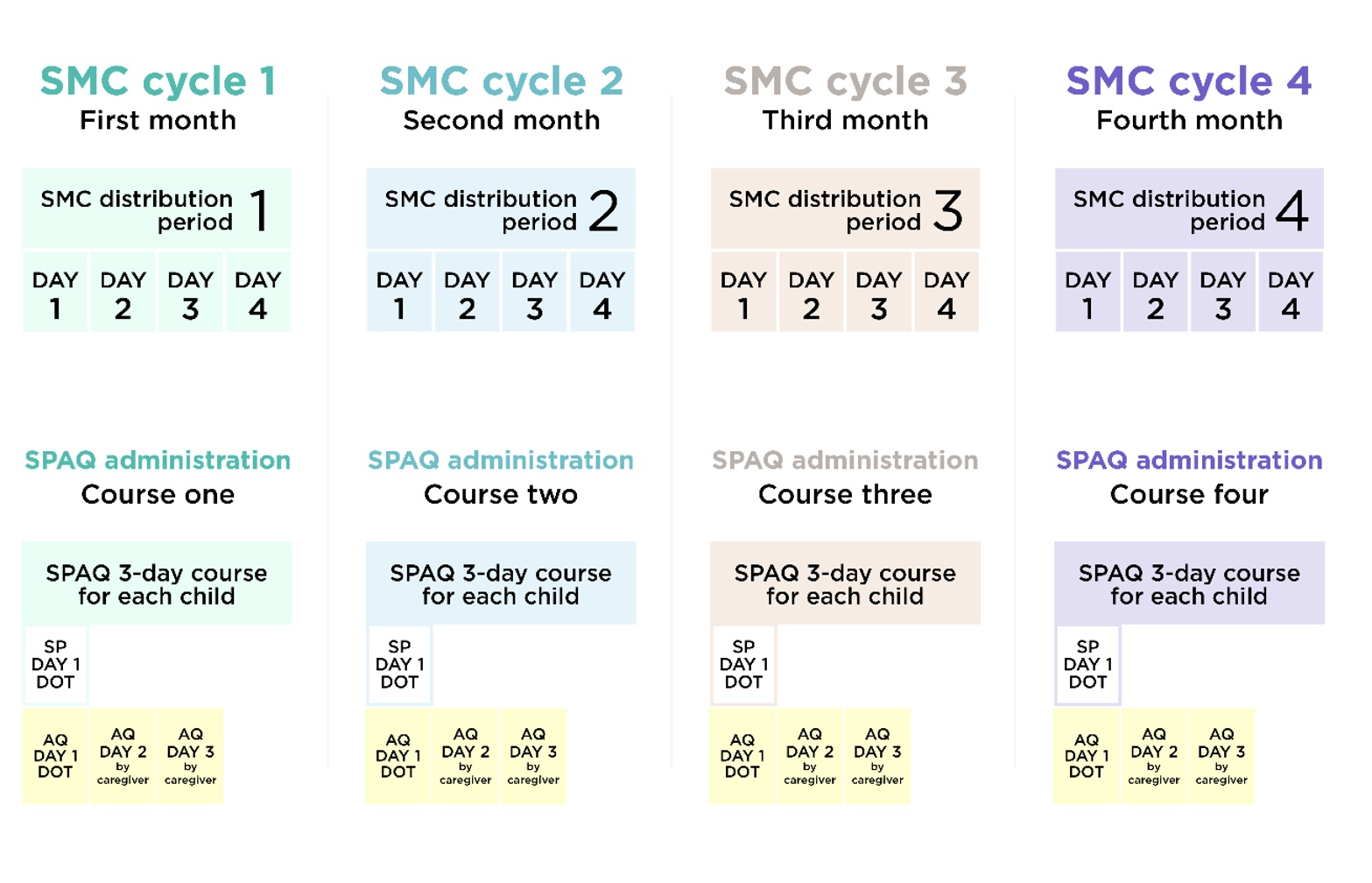

This is a diagram of the delivery schedule (for a four-cycle distribution):

Other relevant aspects of the program are:

- Planning and enumeration. About five months before the SMC round, Malaria Consortium begins planning for the round and budgeting based on enumeration of the target population, personnel, and commodities costs.28

- Procurement and supply management. Malaria Consortium procures SMC drugs and other commodities needed for SMC delivery. Malaria Consortium typically places orders for SMC drugs about a year before the start of the SMC round.29

- Training and supervision. Malaria Consortium trains CDs to identify eligible children, refer sick children to care, and record SPAQ administration.30 We do not know how often CDs follow all of the suggested instructions in practice. Program supervisors oversee CDs to provide mentoring and constructive feedback on implementation.31

- Community engagement. Malaria Consortium supports activities to promote community engagement and social and behavior change before and during SMC campaigns.32

- SMC research. Malaria Consortium also conducts operational research to assess the feasibility and impact of modifying the procedures described above, as well as implementation research and impact analyses. See this spreadsheet for a list of Malaria Consortium's SMC operational research projects in 2019 through 2021.

More details on how Malaria Consortium assesses the coverage achieved by the SMC programs it supports are below.

Malaria Consortium-supported SMC programs

We have seen information from three major SMC projects that Malaria Consortium has supported:

- Pilot and scale-up of SMC in northern Nigeria: The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) provided about $1.7 million to Malaria Consortium to do operational research on the best way to deliver SMC at scale in Katsina state in northern Nigeria, and then to implement its chosen delivery system and assess its efficiency and impact.33 Malaria Consortium told us that it trained over 3,600 CDs and nearly 200 health workers to provide about 1.6 million courses of SMC to roughly 350,000 children who lived in 4 "local government areas" (LGAs) in northern Nigeria in 2012-2014.34 A major goal of the project was to share what it learned; we have seen a published paper that describes the use of research to inform the design of an SMC intervention in northern Nigeria but have not yet reviewed it in detail.35

- ACCESS-SMC:36 Unitaid awarded up to $67 million to Malaria Consortium to lead a project called ACCESS-SMC to reach up to 7 million children per year in seven countries in the Sahel region of Africa in 2015-2017.37 The project, which Malaria Consortium described in 2014 as being the "largest-yet global programme" for SMC, concluded in February 2018.38 ACCESS-SMC was led by Malaria Consortium, with Catholic Relief Services as the "primary sub-grantee" and support from many other organizations, including impact evaluation from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM).39 Malaria Consortium told us that its role in ACCESS-SMC included leading implementation of SMC in three of the seven ACCESS-SMC countries (Burkina Faso, Chad, and Nigeria), overseeing budgets and planning for all ACCESS-SMC activities, and overseeing research (including methodology and presentation).40 Our impression is that ACCESS-SMC paid for almost all aspects of program implementation and monitoring, including medicines and supplies, per diems for CDs, training for CDs, trainers, supervisors, and health facility workers, and research.41 ACCESS-SMC generated evidence for the subsequent scaleup of SMC by providing evidence of impact at scale under programmatic conditions.42

- General SMC program funded primarily by GiveWell-directed funds: Since 2017, Malaria Consortium has been using funding received as a result of GiveWell's recommendation (which we refer to as "GiveWell-directed funds") to support SMC programs in several countries. Over time, the total number of children targeted by these programs has increased from about 660,000 in 2017 to about 12.2 million in 2021. In 2021, Malaria Consortium used GiveWell-directed funds to target approximately 2 million children in 29 districts in Burkina Faso, approximately 1.1 million children in 26 districts in Chad, approximately 8.4 million children in 129 LGAs in Nigeria, and approximately 490,000 children in 19 districts in Togo.43

In 2020-2021, it also conducted implementation research studies delivering SMC in Nampula, Mozambique, where it targeted approximately 70,000 children in two districts,44

and Karamoja, Uganda, where it targeted approximately 90,000 children in two districts.45

In 2021, Malaria Consortium also received funding from the Korea International Cooperation Agency (KOICA) to cover some of the costs of SMC in one state in Nigeria46 and from The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation to cover some of the costs of the research in Mozambique.47 Malaria Consortium co-funded SMC in some health districts in Burkina Faso with UNICEF and in some health districts in Togo with the Global Fund and with UNICEF.48 For this review, we focus on the portion of Malaria Consortium's SMC portfolio that is funded entirely or in part by philanthropic funding, including GiveWell-directed funding. We exclude the portion of Malaria Consortium's SMC portfolio that is funded exclusively by the Global Fund.49

Malaria Consortium's spending on SMC programs

Between January and December 2021, Malaria Consortium spent $50.5 million in GiveWell-directed funds:50

- $17.8 million (35%) on SMC drugs, along with freight and procurement costs

- $19.6 million (39%) on SMC implementation (including planning for SMC campaigns, training of supervisors and CDs, administration of SMC drugs, community engagement, and monitoring and evaluation, including coverage surveys)

- $5.1 million (10%) on staff and travel costs51

- $0.2 million (less than 1%) on equipment

- $1.3 million (2%) on research, communications, and advocacy52

- $6.5 million (13%) on overhead costs

Of this $50.5 million, Malaria Consortium spent $30.7 million (61%) in Nigeria, $9.9 million (20%) in Burkina Faso, $5.4 million (11%) in Chad, 1.7 million (3%) in Uganda, $1.4 million (3%) in Mozambique, and $1.4 million (3%) in Togo, with above-country spending allocated proportionally across countries.53

For prior work, we have also seen spending data from the pilot and scale-up of SMC in northern Nigeria,54 from 2016 for the ACCESS-SMC program,55 and from 2017-20 for programs supported by GiveWell-directed funds.56

We also provide some information on the estimated cost per SMC cycle of Malaria Consortium-supported SMC programs below.

Malaria Consortium's role in SMC programs

Malaria Consortium's SMC work varies by country, but in general aims to support countries' national malaria programs in implementing high-quality SMC campaigns, including the following activities:57

- Determining the quantity of drugs needed, procurement of drugs, and international shipping.58

- Procurement and distribution of other SMC commodities.59

- Funding distributions, including in-country storage and transportation of drugs and payments to front-line distributors to compensate them for the time they spend on the program.

- Technical assistance and logistical support for training SMC implementers, targeted supervision, community engagement and social and behavior change, drug safety, and review of prior implementation and revisions to procedures.

- Financial management and oversight, including disbursing funds to local organizations, Ministries of Health, and/or CDs, collecting and validating receipts, and preparing financial reports.

- Developing training and supervision materials and training staff at various levels.60

- Monitoring and evaluation, including direct observation of program activities by Malaria Consortium staff, funding and coordinating with research firms and academic institutions to conduct coverage surveys and to track changes in malaria incidence and death, and monitoring of drug resistance.

- Advocacy and fundraising with governments, international, multinational, and bilateral organizations, donors, SMC working groups, researchers, and civil society.

- Conducting research that addresses knowledge gaps relating to SMC delivery, quality, and impact, writing and disseminating lessons learned and publications in peer-reviewed journals, and presenting at international global health conferences. See this spreadsheet for a list of Malaria Consortium's SMC research projects in 2019-2021.

- In 2020, in order to continue implementing SMC during the COVID-19 pandemic, Malaria Consortium established enhanced safety and infection prevention guidance for program delivery, which included providing guidance for SMC delivery by community distributors, procuring items such as face masks and hand sanitizer, and revising training and supervision documents and job aids. In 2021, Malaria Consortium revised its infection prevention guidance for use during 2021 SMC rounds.61

Does it work?

We base our expectation of the impact of Malaria Consortium's SMC programs on:

- The evidence of effectiveness of SMC at reducing malaria incidence.

- Characteristics of the areas targeted by Malaria Consortium's SMC programs (including malaria incidence and seasonality).

- Evidence that a high proportion of targeted children have received SMC in past rounds.

We believe that the above provides strong indirect evidence that Malaria Consortium's SMC programs reduce malaria incidence in the populations they target. We also consider whether there is direct evidence of such reductions in these populations.

Finally, we consider whether there are factors that are not accounted for in the above evidence that would offset the impact of Malaria Consortium's SMC programs, either through reducing their effectiveness or contributing to negative outcomes.

Is SMC an effective intervention?

Seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) provide strong evidence that SMC substantially reduces cases of malaria. We discuss this evidence in our intervention report on SMC. We incorporate SMC's impact on malaria incidence, as measured by these RCTs, into our cost-effectiveness model.62

Are Malaria Consortium's SMC programs targeted at areas where they are likely to be effective?

Malaria Consortium told us that before starting work in countries under the ACCESS-SMC program, it conducted an assessment of the overall burden of malaria, transmission and rainfall patterns, regional malaria incidence over time, and seasonal variations in malaria.63 We have not reviewed this evidence in detail, but it seems highly likely to us that Malaria Consortium is working in areas that are suitable for SMC because it is working in countries with high malaria burdens and where it seems that malaria is seasonal.64 More information on our estimates of malaria burden in the countries where Malaria Consortium is working is available in our cost-effectiveness model.65

Are targeted children reached with SMC?

Malaria Consortium conducts coverage surveys to determine what proportion of the target population (children aged 3-59 months) was reached with SMC in the previous round or cycle. We use results from past SMC rounds to understand the impact we should expect future rounds to have. Specifically, we use coverage survey results about the proportion of targeted children reached, along with data on program spending, to estimate the cost of delivering SMC to a child. Our interpretation of these coverage survey results is informed by their comprehensiveness and the methodology used to collect them.

Comprehensiveness

See this spreadsheet for all coverage survey results we have seen from Malaria Consortium's SMC programs. In short, we have seen results from all large-scale SMC programs66 that Malaria Consortium supported with GiveWell-directed funds through 2021. This includes results from 2017-2021 in Burkina Faso, Chad, and Nigeria, from 2020-2021 in Togo, and from 2021 in Uganda and Mozambique.67

We have also seen results from 2015-2016 in the seven countries that Malaria Consortium supported through the ACCESS-SMC project. We thus believe that we have seen a thorough picture of the impact of Malaria Consortium's SMC program; we incorporate this assessment into our cost-effectiveness model.68

We focus our review on results from 2017 onward in Burkina Faso, Chad, and Nigeria and from 2020 onward in Togo, as we believe they are more likely to be indicative of what we can expect from future SMC rounds in those countries. We do not focus on results from Mozambique and Uganda because Malaria Consortium was operating at a small scale and doing implementation research in these countries in 2021, so we don't expect results to provide a good indication of the coverage that it might achieve in future program years.69

Methodology

Since 2017, Malaria Consortium has conducted two types of coverage surveys. After all but the final cycle in the SMC round, it conducts a post-cycle coverage survey to measure coverage in the previous cycle only.70 After the final cycle in the SMC round, it conducts a post-round coverage survey to measure coverage across the full round.71 Both post-cycle and post-round surveys involve household interviews with caregivers of SMC-eligible children. Full details of the methodology used in the surveys we have reviewed are in the "Methods" sheets of this spreadsheet.

Below, we summarize Malaria Consortium's general post-cycle and post-round coverage survey methodology and discuss methodological strengths and weaknesses. Overall, we believe that both types of surveys are designed to measure key indicators of the success of SMC campaigns and to achieve samples that are generally representative of target populations. However, we are concerned that the self-reported nature of responses and data collectors' involvement in the later stages of respondent selection may produce bias in results. In general, we have also been uncertain about the quality of survey implementation due to the lack of a procedure to audit data collectors' work; in 2021, auditing measures were introduced into post-round and post-cycle surveys in Nigeria (and post-round surveys in Mozambique and Uganda).72 We see this as a methodological strength, both because such a procedure may encourage accurate data collection and because it provides a check on the accuracy of results. Results from the auditing of post-round surveys in Nigeria suggest that in the vast majority of cases, data collection procedures were followed correctly, though some instances of interviews being done incorrectly or results being fabricated were found.73 We incorporate our assessment of the quality of Malaria Consortium's coverage survey methodology into our cost-effectiveness model74 and into our qualitative assessment of Malaria Consortium's organizational strength.

- Respondent selection: Post-cycle surveys employ lot quality assurance sampling75

in which the program area is subdivided into smaller units, generally of approximately equal population size, and a small number of households is randomly selected from each unit.76

While this approach is primarily designed to assess whether each unit met a target coverage level, data from all units can be aggregated to calculate coverage across the program area. Because all units are sampled and are of approximately equal population size, we expect this selection protocol to result in a sample that is generally representative of the target population.77

Post-round surveys employ multi-stage cluster sampling of households in the program area, with sampling units above the household level generally selected randomly with probability proportional to size.78

We expect this selection protocol to result in a sample that is generally representative of the target population.

For both types of surveys, data collectors are instructed to randomly select households to survey. In some surveys we have reviewed, data collectors were instructed to use numbered household lists from which they selected households using randomly generated numbers. In other surveys, data collectors were instructed to spin a bottle at a central point in the community to choose a direction along which they then selected a predetermined number of households at a predetermined interval.79 This latter method may lead households closer to the center of a community to be overrepresented in the sample. We are unsure of how this might bias results, though it seems plausible that households on the outskirts of a community may have been less likely to be reached by SMC, and thus that results would be biased upward.

Next, data collectors enter all children aged 3-59 months (the eligible age range for SMC) in the selected household into survey software. The survey software then randomly selects a child, and data collectors ask caregivers questions about that child.80

We see it as a methodological strength that child selection is randomized by survey software. However, we see data collectors’ involvement in the later stages of respondent selection as a potential concern. Data collectors may apply selection procedures incorrectly, either unintentionally or intentionally. If, for example, they purposefully select households that are easier to reach, this would be a potential source of upward bias, as households that are easier to reach may also have been more likely to be reached by SMC. We note that we have seen no evidence that data collectors intentionally applied selection procedures incorrectly and note it only as a possibility.

If a selected household is unavailable or refuses to participate in the survey, data collectors are instructed to move to the next household according to the sampling procedure. In the 2019-21 post-round surveys, 98% or higher of the targeted number of households were interviewed.81 This could mean that non-response rates (i.e., households randomly selected to be interviewed not being interviewed) were low. However, because we do not know how often replacement households were used, it is also possible that a high proportion of interviewed households were replacement households, so these survey completion rates only slightly increase our confidence in the accuracy of results from these surveys. The post-cycle survey completion rates for 2020-2021 from Burkina Faso, Chad, Nigeria, and Togo were 90% or higher, with the exception of Plateau state in Nigeria in 2021.82

- Survey design: Malaria Consortium has developed post-cycle and post-round questionnaires,83

which are adapted for use in each country. Questionnaires are translated from English into French in Burkina Faso, Chad, and Togo, and into Portuguese in Mozambique.84

These questionnaires instruct data collectors to ask caregivers questions about whether their child received SPAQ during the previous cycle (in the case of post-cycle surveys) or during all cycles of the round (in the case of post-round surveys). Both questionnaires ask about SPAQ provided by a CD on the first day of each cycle and about AQ provided by the caregiver on the second and third days of each cycle. They also ask questions about the quality of program delivery. Data collectors translate questions from English, French, or Portuguese into local languages during household interviews,85

which may lead to inconsistencies in translation and reduce the accuracy of results.

A potential source of bias in Malaria Consortium's coverage surveys is their heavy reliance on self-reported responses. Post-round responses are at high risk of recall bias, as they report on up to 12 or 15 doses,86 the first of which would have occurred at least three or four months prior.87 Post-cycle responses are at lower risk of recall bias, as they ask only about three doses and are conducted within two weeks to a month of those doses.88 Self-reported responses are also at risk of social desirability bias that could lead caregivers to overreport SMC administration, if they believe that this is the preferred response of data collectors. We expect responses about caregivers' own administration on the second and third days of each cycle to be at greater risk of this type of bias, as they may feel pressure to overreport their own adherence to program guidance. Because the coverage estimates we use are based on responses about CDs' administration on the first day of each cycle,89 about which we believe caregivers may feel less pressure to report positively, this is a smaller concern.

We would have more confidence in a survey that tested the reliability of self-reported responses against some objective measure. In order to verify caregiver responses, data collectors are instructed to review children's SMC record cards and drug blister packs, if available.90 However, retention of these items has generally been low, leading Malaria Consortium to place low weight on them as indicators of coverage.91

- Survey implementation: In general, Malaria Consortium contracts with local research organizations that recruit data collectors and oversee survey implementation.92

Individuals involved in the surveys generally were not involved in SMC delivery, which suggests that they are unlikely to have a personal interest in survey outcomes.93

Malaria Consortium has reported a few cases in which surveys conducted by local research organizations were of low quality;94

this may have impacted the accuracy of results, but we are uncertain about the magnitude or direction of this impact.

Malaria Consortium's coverage surveys have not systematically incorporated an auditing procedure to assess the accuracy of data collectors' work. In 2021, auditing measures were introduced into post-round and post-cycle surveys in Nigeria (and post-round surveys in Mozambique and Uganda).95 We see this as a methodological strength, both because such a procedure may encourage accurate data collection and because it provides a check on the accuracy of results. We have not seen results from the audits of Nigeria post-cycle and Mozambique and Uganda post-round surveys. We have seen results from the audits of post-round surveys in Nigeria in 2021, for which several methods were in place to check enumerators' entries: supervisors tracked enumerators' GPS locations to ensure that they visited the correct communities, listened to a portion of audio recordings taken of interviews, and re-surveyed a portion of households to check that interviews had been conducted according to survey protocol. The vast majority of supervisor re-surveys uncovered no issues, which increases our confidence that data collection procedures were usually followed correctly. However, decreasing our confidence in results is the fact that 3% of the interviews that were subject to GPS auditing and 4% of the interviews that were subject to audio auditing were done incorrectly or fabricated. While these results were then removed from the data set, their random selection suggests that a similar proportion of the unaudited results could have issues. (We aren't sure how to reconcile the different rates of issues found by supervisor re-surveys and GPS and audio auditing.)96 In addition, we have seen data from repeat interviews conducted in Nigeria in 2017.97

- Data capture: Data is collected electronically in both post-cycle and post-round coverage surveys and uploaded to a remote server at the end of each day of data collection.98 One concern we have about coverage surveys in general is that data may be lost after being collected. As mentioned above, from 2019-2021, data was collected and uploaded from 98% or higher of the number of households that were targeted to be interviewed in post-round surveys and from 90% or higher of households targeted in post-cycle surveys in 2020-2021. This leads us to believe that it is unlikely that substantial data loss occurred after collection.

Results

We believe that results from Malaria Consortium's coverage surveys provide strong evidence that a high proportion of the target population was reached with SMC in past rounds. We use these coverage estimates, along with data on program spending, to estimate the cost of delivering SMC to a child.

See this spreadsheet for all results we have seen from Malaria Consortium's SMC programs. Results weighted by target population from post-round surveys in 2017-2021 show that across those years, for children targeted to receive four cycles of SMC, 95% were covered by SMC for at least one monthly cycle, 88% for at least two cycles, 77% for at least three cycles, and 65% for all four cycles.99 In the most recent program years, post-round surveys measured average coverage across cycles at 92% in Burkina Faso (2018-2020), 85% in Chad (2018-2021), 78% in Nigeria (2018-2021), and 87% in Togo (2020-2021).100

For coverage surveys in 2017-2021, we have compared results from post-cycle and post-round surveys. After converting the two sets of coverage estimates into a measure of total person-months of coverage for comparison, we find a difference of 2% between them for 2017, 13% for 2018, 24% for 2019, 9% for 2020, and 6% for 2021.101 We find it concerning that this difference is high in some years. We don't know why, overall, it increased from 2017-2019 and then decreased in 2020 and 2021, but we have attempted to understand the main drivers of this difference for each year. In general, the difference has been driven by results from Nigeria, with results from Chad also contributing to the difference in 2019.102 From 2018 to 2021, post-cycle results found higher person-months of coverage than post-round results.103 Differences in sampling protocol and questionnaire design between the two types of surveys may inevitably lead to some difference in results. However, the fact that post-cycle and post-round results were similar in Burkina Faso in 2017-2020, in Chad in 2017-2018 and 2020-2021, and in Nigeria in 2017 leads us to believe that larger discrepancies cannot be explained merely by methodological differences and likely result from biases present in the surveys in Chad in 2019 and in Nigeria in 2018-2021. In cases where the discrepancy is large, we believe that the post-round results are a better indication of actual coverage104 and have chosen to use these results to estimate the cost of delivering SMC to a child.

Have malaria rates decreased in targeted populations?

The evidence we have discussed to this point forms the basis of our expectation of the impact of Malaria Consortium's SMC programs. In this section, we consider whether there is additional evidence on the impact or efficacy of SMC that either corroborates this expectation or raises concerns that Malaria Consortium's programs are not achieving the impact we expect.

Sentinel surveillance site data (2013-2016)

We have seen sentinel surveillance site data from Chad, Mali, and Niger for 2013 to 2016 and from Burkina Faso and Nigeria for 2015 to 2016.105 We have received only headline figures for the reduction in malaria cases in children under 5 years old; we have not seen additional information on the sources for or analysis of this data.106 We have therefore not vetted the results (described in the footnote).107 Malaria Consortium told us that the data collected in other ACCESS-SMC countries was of a low quality.

Health Management Information System (HMIS) data

In 2019, Malaria Consortium conducted an assessment of the impact of SMC on malaria rates in Burkina Faso and Chad from 2013 to 2018 and Nigeria from 2017 to 2018, using national HMIS data.108 This assessment found no evidence of impact.109 Malaria Consortium attributes this result to several factors, in particular the variable and generally low quality and completeness of HMIS data used in the analysis.110

Malaria Consortium notes that it chose to analyze HMIS data, despite the fact that it is typically of low quality, because it is an inexpensive and commonly used source of impact data and therefore a relatively sustainable method for assessing impact over the long term.111 Given our understanding that collecting high-quality health facility data is difficult, we find Malaria Consortium's explanation plausible.

Our overall assessment of the expected impact of SMC places little weight on the lack of impact found in HMIS-based impact assessments because:

- Non-randomized comparisons between areas in which SMC is implemented and not implemented may over or understate the impact of SMC due to differences in the two groups other than presence of SMC.

- We believe that there is a risk that data quality limitations will be emphasized more where non-positive trends are found than where positive trends are found. Independently assessing the quality of HMIS data would be a large project for us and we have not prioritized that work.

As noted above, we base our expectation of the impact of Malaria Consortium's SMC programs on malaria rates on the evidence of effectiveness of SMC at reducing malaria incidence, as measured by RCTs, and evidence from Malaria Consortium's coverage surveys that a high proportion of targeted children have received SMC.

Case-control studies

Malaria Consortium also shared case-control studies designed to measure the efficacy of SMC from five ACCESS-SMC countries: Burkina Faso, Chad, The Gambia, Mali, and Nigeria. We have not yet vetted the methodology (some details in the footnote), and the dataset from Nigeria did not pass quality control.112 Malaria Consortium's conclusion from these studies is, "These results confirm that SMC treatments are providing a very high degree of personal protection from malaria for a period of 28 days after each treatment. Protection then declines rapidly emphasizing the importance of repeating treatments at monthly intervals."113 More details on those results in this footnote.114

Northern Nigeria (2012-2014)

We have seen three types of analyses of the impact of Malaria Consortium's northern Nigeria program on malaria indicators. These results seem to be consistent with the impacts of SMC found in randomized controlled trials of the program, but due to our remaining questions about the studies we do not yet see them as strong additional evidence for the impact of SMC programs. See our previous review of Malaria Consortium for more details on this study.

Are there any negative or offsetting impacts?

In this section, we consider factors that are not accounted for in the above evidence that could offset the impact of Malaria Consortium's SMC programs, either through reducing their effectiveness or contributing to negative outcomes.

- Drug resistance: Mass delivery of SMC medicines could contribute to increased drug resistance of SP and/or AQ.115 In 2015, ACCESS-SMC funded a baseline study of the prevalence of gene mutations in malaria parasites that are markers of drug resistance for the drugs used in SMC.116 A follow-up survey was conducted in 2017, following two rounds of SMC.117 We have lightly reviewed a preliminary report from this survey, which reported that between baseline and follow-up, the prevalence of mutations associated with AQ resistance did not increase and that the prevalence of mutations associated with SP resistance did increase.118 It also reported that no samples were collected that contained both mutations associated with AQ resistance and mutations associated with SP resistance.119 We have received the final report from this survey but have not yet reviewed it in depth. In our cost-effectiveness model, we make a small downward adjustment in our estimate of SMC's impact to account for the possibility of development of drug resistance.120

- Possible "rebound" effects: There is a potential concern that SMC could reduce the natural development of immunity to malaria. After children turn five years old and are no longer eligible to receive SMC or if SMC programs are interrupted by lack of funding or other problems, children could lack immunity and be more susceptible to malaria, especially if other prevention methods, such as long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs), are not used. We have not yet investigated this concern in-depth. In our cost-effectiveness model, we make a small downward adjustment in our estimate of SMC's impact to account for the possibility of rebound effects.121

- Side effects of SMC drugs: Our impression is that the most common reaction seen with SMC drugs in earlier programs was vomiting (AQ is bitter and had to be crushed into a powder and mixed with water); for a number of years, AQ has been available as an orange-flavored dispersible, which improves the taste and makes the drug more easily ingestible.122 Malaria Consortium told us that the incidence of vomiting has decreased with the dispersible formulation.123 If the child expels the drugs within 30 minutes, they are supposed to be re-dosed once; we are unsure whether caregivers typically request extra tablets of AQ from CDs when this happens at home to ensure their child gets a full course of SPAQ.124 Our impression is that other side effects from these drugs are rare and include diarrhea, itching, headache, mild abdominal pain, and rash.125 Severe adverse effects associated with SPAQ are rare. A study in Nigeria that followed up with 10,000 SMC recipients one week after receiving SMC resulted in only five reports of severe adverse events, though Malaria Consortium believes there may have been reluctance to report issues.126 Malaria Consortium shared three resources that report very low severe adverse event rates from SMC drugs (available in the following footnote).127 We have lightly reviewed resources on severe adverse event rates from SMC drugs here. In our cost-effectiveness model, we make a small downward adjustment in our estimate of SMC's impact to account for the possibility of severe adverse effects.128

- Drug quality and dosage: Malaria Consortium told us that its policy is to only procure products from suppliers that meet WHO guidelines for pre-qualification quality assurance standards,129 and that these products are approved and quality-assured by the governments of countries where Malaria Consortium works.130 We have not yet asked Malaria Consortium for the details of these processes. If there were issues with drug quality or dosage, it could reduce the effectiveness of the intervention and lead to more rapid development of drug resistance.

What do you get for your dollar?

Cost per SMC cycle administered

In order to make program costs comparable across all of our top charities, we aim to estimate the total cost to all actors of supporting a given program. Our estimate of the cost per SMC cycle administered includes research costs and costs incurred by actors such as governments. Our estimates rely on coverage survey estimates to approximate the number of children reached.

With these assumptions, using information from Malaria Consortium's programs between 2018 and 2021, we estimate that the total cost to achieve the equivalent of one person-month of SMC coverage is about $1.50. We have access to cost and coverage data starting in 2015 for Burkina Faso, Chad, and Nigeria;131 however, we have chosen to include data only from more recent years because we believe it provides a better indication of the cost per SMC cycle administered that Malaria Consortium will achieve in future years. (The downside of this approach is that our estimates of cost per SMC cycle administered exclude start-up costs, though these costs are a sufficiently small proportion of total costs over time that their exclusion does not substantially impact our estimates.) Full details and country-specific estimates are available in this spreadsheet.132

We start with this total cost figure and apply adjustments in our cost-effectiveness analysis to account for cases where we believe the charity's funds have caused other actors to shift funds from a less cost-effective use to a more cost-effective use ("leverage") or from a more cost-effective use to a less cost-effective use ("funging").

Cost-effectiveness

See our page on impact estimates for estimates of the cost per life saved through Malaria Consortium-supported SMC programs and how our model compares this outcome with outcomes of other programs.

Note that our cost-effectiveness analyses are simplified models that do not take into account a number of factors. For example, our model does not include the short-term impact of non-fatal cases of malaria prevented. It also does not include possible offsetting impacts or other harms.133

There are limitations to this kind of cost-effectiveness analysis, and we believe that cost-effectiveness estimates such as these should not be taken literally, due to the significant uncertainty around them. We provide these estimates (a) for comparative purposes and (b) because working on them helps us ensure that we are thinking through as many of the relevant issues as possible.

Is there room for more funding?

We conduct "room for more funding" analysis to understand what portion of Malaria Consortium's ideal future budget it will be unable to support with the funding it has or should expect to have available. We may then choose to either make or recommend grants to support those unfunded activities. Our recent analyses of Malaria Consortium's room for more funding can typically be found by visiting the "Sources" sections of our published grant pages (see a list of grant pages here).

Room for more funding analysis

In general, we assess top charities' funding needs over a three-year period.134 We ask top charities to report their ideal budgets over the next three years, along with information about their current available funding and funding pipeline. The difference between a charity's three-year budget and the funding we project that it will have available to support that budget is the charity's "room for more funding."

For this analysis, we focus on the portion of Malaria Consortium's SMC portfolio that is funded entirely or in part by philanthropic funding, including GiveWell-directed funding. We exclude the portion of Malaria Consortium's SMC portfolio that is funded exclusively by institutional funding.135

The main components of our room for more funding analyses are:

- Available funding. We ask top charities to report how much funding they currently hold in the bank, including in reserves, and how much of this funding is committed or expected to be spent on specific future activities. The difference between these figures is the amount available to allocate to the charity's unfunded spending opportunities.

- Expected funding. We project the amount of additional funding that top charities will receive to support their work over the next three years. These projections represent our best guesses based on top charities' past revenue and our understanding of their funding pipelines. They typically include funding currently held by GiveWell to be granted to the top charity, projected funding due to being a GiveWell top charity,136 and, if the top charity is part of a larger organization, projected unrestricted funding from that parent organization. They exclude any funding we may specifically recommend to the top charity subsequent to the analysis. We add this projected funding to the amount available to allocate to the charity's unfunded spending opportunities.

- Spending opportunities. We ask top charities to report their ideal budgets in each of the next three years and to provide details on the specific spending opportunities included in these budgets. These opportunities are typically presented as one program year in a specific implementation geography (for example, SMC in Nigeria in 2023), and they can represent either an extension of the top charity's previous support to a geography or an expansion of support to a new geography. We ask top charities to report the order in which they would prioritize funding these opportunities, which helps us to understand how available and expected funding will be allocated and what the marginal impact of additional funding beyond that amount would be.

A charity's room for more funding represents the total budget for the charity's spending opportunities, less its available and expected funding. For example, if a charity proposes spending $50 million over the next three years and holds $10 million in uncommitted funding, and we project that it will receive an additional $15 million in revenue over the next three years, that charity's room for more funding is $25 million. (Note that a charity's total room for more funding figure includes funding gaps at all levels of cost-effectiveness—see below.) Our recent analyses of Malaria Consortium's room for more funding can typically be found by visiting the "Sources" sections of our published grant pages (see a list of grant pages here).

Grant investigation process

Room for more funding analysis is a key part of our grant investigation process. We periodically request the information described above from top charities and update our room for more funding analyses. Our default is to update each top charity's room for more funding analysis annually, though we may choose to do so more or less frequently. The cadence on which we conduct updates depends largely on how often we grant funding to a top charity137 and how much we expect that charity's funding and budgets to have changed since our most recent funding decision.138 We have typically updated our analysis of Malaria Consortium's room for more funding on an annual basis, and have completed additional ad hoc updates prior to large grant decisions. Our recent analyses of Malaria Consortium's room for more funding can typically be found by visiting the "Sources" sections of our published grant pages (see a list of grant pages here).

After completing such an update, we may then choose to investigate potential grants to support the spending opportunities that we do not expect to be funded with the charity's available and expected funding, which we refer to as "funding gaps." The principles we follow in deciding whether or not to fill a funding gap are described on this page.

The first of those principles is to put significant weight on our cost-effectiveness estimates. We use GiveDirectly's unconditional cash transfers as a benchmark for comparing the cost-effectiveness of different funding gaps, which we describe in multiples of "cash." Thus, if we estimate that a funding gap is "10x cash," this means we estimate it to be ten times as cost-effective as unconditional cash transfers. As of this writing in January 2023, we are focused on funding opportunities that meet or exceed a relatively high bar: 10x cash, or ten (or more) times as cost-effective as GiveDirectly's unconditional cash transfers. (Note that a charity's total room for more funding figure includes funding gaps at all levels of cost-effectiveness.)

If we decide to fill a funding gap, we either make a grant from our Top Charities Fund139 or recommend that another funder—typically Open Philanthropy140 —makes a grant. This page lists all grants made or recommended by GiveWell. Typically, when GiveWell donors make a donation to a top charity,141 we don't expect that donation to be directed to a specific funding gap, but rather to contribute to supporting the overall portfolio of opportunities included within a charity's room for more funding.

Availability of unrestricted funding

Since Malaria Consortium works on a variety of programs, it is possible that receiving additional funds for its SMC work could lead it to reallocate unrestricted funds or other organizational resources (such as time spent fundraising) toward other programs, so that additional dollars donated to Malaria Consortium would not fully support additional SMC work. However, we do not see this as a major concern because we do not believe that Malaria Consortium has substantial unrestricted funding available, and it seems that Malaria Consortium has not allocated substantial unrestricted funding to SMC work in the past (see footnote for details).142

Malaria Consortium as an organization

We use qualitative assessments of our top charities to inform our funding recommendations. See this page for more information about this process and for our qualitative assessment of Malaria Consortium as an organization.

Sources

- 1

For an overview of Malaria Consortium's 2021-25 strategy, see this page.

- 2

- We had one conversation with Malaria Consortium staff in each of January, February, and March, 2016.

- GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Malaria Consortium Staff, August 25, 2016.

- GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of conversations with Malaria Consortium staff, November 7 and November 9, 2016.

- GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Malaria Consortium Staff, November 23, 2016.

- GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Malaria Consortium staff, January 18, 2017.

- GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Malaria Consortium staff, January 19, 2017.

- GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Malaria Consortium staff, March 24, 2017.

- GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of a conversation with Diego Moroso, April 25, 2017.

- Starting in 2017, we deprioritized publishing notes from our conversations with Malaria Consortium. We continued speaking regularly with Malaria Consortium staff in 2017-2018.

- 3

- 4

"Established in 2003, Malaria Consortium is one of the world’s leading non-profit organisations specialising in the prevention, control and treatment of malaria and other communicable diseases among vulnerable populations.

Our mission is to improve lives in Africa and Asia through sustainable, evidence-based programmes that combat targeted diseases and promote child and maternal health." Malaria Consortium website, "Who We Are".

- 5

- Malaria Consortium, comments on a draft of this page, December 2022.

- "Established in 2003, Malaria Consortium is one of the world’s leading non-profit organisations specialising in the prevention, control and treatment of malaria and other communicable diseases among vulnerable populations.

Our mission is to improve lives in Africa and Asia through sustainable, evidence-based programmes that combat targeted diseases and promote child and maternal health." Malaria Consortium website, "Who We Are".

- 6

- Malaria Consortium spent 66,822,000 British pounds from April 1, 2020 to March 31, 2021. See Malaria Consortium, Trustees' report and financial statements for the year to 31 March 2021, Pg. 24, "Total expenditure" under column "Group 2021 Total Funds."

- We used X-RATES to find the GBP to USD conversion rate as of March 31, 2021: 1.3798. 66,822,000 x 1.3798 = $92,200,996.

- Percentage of spending coming from restricted funds calculation: (29,291,000 + 33,417,000) / 66,822,000 British pounds = 0.94. See Malaria Consortium, Trustees' report and financial statements for the year to 31 March 2021, p. 24, and compare "Restricted funds" and "Total funds" columns for the "Total expenditure" row from "Group 2021."

- 7

"In March 2012, the World Health Organisation (WHO) issued a policy recommendation for a new intervention against Plasmodium falciparum malaria - seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), previously referred to as intermittent preventive treatment in children (IPTc), in children under five years old. SMC is defined as the intermittent administration of full treatment courses of an anti-malarial treatment combination during the malaria season to prevent illness and death from the disease.

The objective is to maintain therapeutic anti-malarial drug concentrations in the blood throughout the period of greatest risk. This will reduce the incidence of both simple and severe malaria disease and the associated anaemia and result in healthier, stronger children able to develop and grow without the interruption of disease episodes. SMC has been shown to be effective, cost effective and feasible for the prevention of malaria among children in areas where the malaria transmission season is no longer than four months." Malaria Consortium website, "Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention".

- 8

"Across the Sahel sub-region, most childhood malarial disease and deaths occur during the rainy season, which is generally short (3-4 months). Giving effective antimalarial treatment at monthly intervals during this period has been shown to be 75% protective against uncomplicated and severe malaria in children under 5 years of age." World Health Organization, "Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention".

- 9

World Health Organization, "Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention: A Field Guide," 2013, Pg 7.

- 10"The original recommendation restricted SMC use to the Sahel subregion of Africa; SMC could not be recommended, at the time, in areas outside the Sahel with highly seasonal malaria transmission, such as in southern Africa, due to high levels of resistance to the medicines (SP and AQ) in those areas." WHO, Updated WHO recommendations for malaria chemoprevention among children and pregnant women, June 2022

- 11 "The original recommendation restricted SMC use to the Sahel subregion of Africa; SMC could not be recommended, at the time, in areas outside the Sahel with highly seasonal malaria transmission, such as in southern Africa, due to high levels of resistance to the medicines (SP and AQ) in those areas. The updated recommendation recognizes that countries in other parts of Africa with highly seasonal variation in malaria burden could also benefit from SMC, and that the availability of new medicines could make it a viable intervention in these areas.

The original recommendation stated that a maximum of 4 monthly doses of SMC should be given during the malaria transmission season. The updated guidance states that SMC should be given during peak malaria transmission season, without defining the specific number of monthly cycles. … While the original recommendation restricted SMC use to children less than 6 years of age, the new recommendation recommends this intervention for children at high risk of severe malaria, which may extend to older children in some locations." WHO, Updated WHO recommendations for malaria chemoprevention among children and pregnant women, June 2022

- 12

Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2020, Pg. 5.

- 13

- "How is SMC delivered?

Local announcements each month will inform the community about the date of SMC, which will be delivered by community health workers at pre-arranged locations in the community, or by visiting each household. Health workers will receive appropriate training before the intervention begins and will be supervised by nurses and the district health team."ACCESS-SMC project brochure, Pg 3. Malaria Consortium noted that health workers are also sometimes trained for SMC programs (comment provided in response to a draft of this page in October 2017). - For Malaria Consortium's SMC program in Nigeria: "House to house delivery method was the most used approach, as reported by 88.2 percent of the respondents. This was similar across the LGAs [local government areas] though Maiadua had slightly higher numbers receiving through the fixed point delivery approach. The duration spent in receipt of drugs in the home was 20 minutes, half the time spent in receipt of drugs from a fixed point which was 47 minutes. Knowledge of the different types of SMC drugs and dose duration was high at over 80 percent. This highlights house to house delivery of SMC as a quicker and most preferred delivery mechanism by the caregivers. There is need for costing the two delivery mechanisms to assess if home based delivery still remains a cost effective delivery channel." Malaria Consortium, Nigeria SMC evaluation report, 2014, Pg 38.

- For ACCESS-SMC delivery methods, see the annexes on Pgs 31-70 of ACCESS-SMC multi-country cost analysis, January 2017. Sample quote: "A combination of 6,500 trained community distributors and 355 health facility staff (e.g. nurses and midwives) administered SMC by way of two distribution methods: door-to-door (two-person teams) and at fixed points located at health centers (one-person teams) which were in place to serve primarily as referral centers for sick children and provide SMC to children who were came to the facility. It was estimated that 90% of SMC was distributed by door-to-door teams and 10% was distributed at fixed points. To ensure the acceptability of SMC and high rates of coverage within communities, 3,483 trained community mobilizers sensitized communities on the benefits of SMC prior to and during each distribution cycle." ACCESS-SMC multi-country cost analysis, January 2017, Pg 31.

- "[Delivery from pre-arranged locations in the community] was for ACCESS only. Now is mostly [household to household]." Malaria Consortium, comments on a draft of this page, October 2019.

- "How is SMC delivered?

- 14

"Some community distributors are community health workers — a recognized cadre of community-based primary healthcare workers who receive a small stipend from the government and who provide basic health services in their communities. In most countries, the majority of community distributors are volunteers recruited and trained specifically for the SMC campaign. Community distributors typically work in pairs." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 13.

- 15

Malaria Consortium emails (unpublished), November 23, 2016.

Comments from Malaria Consortium in response to a draft of this page in October 2017. - 16

"During SMC distribution, community distributors are assisted by field supervisors who receive more in-depth training on supervision and mentoring skills. Each team of community distributors should be observed by, and receive constructive feedback from, a supervisor at least once every cycle. Supervision is coordinated by health workers at the health facilities that serve as functional units for SMC distribution, sometimes with support from community health workers. Malaria Consortium staff and local, regional, and central health authorities also support the supervision of SMC implementers." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 14.

- 17

- "In 2021, the malaria programs in Burkina Faso, Nigeria, and Uganda introduced five monthly SMC cycles in areas where the transmission season is slightly longer." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, Pg. 17.

- Uganda: "In 2020, the National Malaria Control Division (NMCD) approached Malaria Consortium with a request to support an SMC implementation study in Karamoja (Figure 13) to investigate the feasibility, acceptability, and impact of SMC. The study employs a similar two-phase design as the study Malaria Consortium is conducting in Mozambique and is described in more detail in the research section below. The first project phase involved SMC delivery to around 90,000 children in two districts. Taking into account local malaria transmission patterns, five SMC cycles were implemented between May and September 2021." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 37.

- 18

- See Figure 1, Pg 8, Malaria Consortium, "Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention Programme Start-Up Guide, Nigeria"

- "All three countries are now delivering SMC over 4 days. Previously in ACCESS SMC some countries implemented over 5 days." Malaria Consortium, comments on a draft of this page, October 2020.

- "Typically, all eligible children in a given area will be reached over a distribution period of four or five days per cycle, which is repeated monthly over the course of the transmission season." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 13

- 19

See Malaria Consortium, 2018 SMC Coverage Report, Table 1, Pg. 8 for an overview of SMC procedures.

- 20

Malaria Consortium emails (unpublished), November 23, 2016.

- 21

- "Those who have a fever or are unable to take oral medication should not receive SPAQ from community distributors, but will be referred to a qualified health worker for further assessment and testing for malaria infection using a rapid diagnostic test (RDT)." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 13

- Sick children can be referred to a qualified community health worker in Uganda. Christian Rassi, Program Director - Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention, Malaria Consortium, Comments on a draft of this page, December 2022.

- 22

- See Figure 1, Pg 8, Malaria Consortium, "Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention Programme Start-Up Guide, Nigeria". "DOT" stands for "Directly Observed Treatment".

- "Day 1 SP and AQ should be administered by the drug distributor as DOT.

If the child vomits or spits out the drugs within 30 minutes, a second dose should be given." Table 1, Pg. 8, Malaria Consortium, 2018 SMC Coverage Report. - Malaria Consortium, comments on a draft of this page, October 2019.

- 23

- See Figure 1, Pg 8, Malaria Consortium, "Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention Programme Start-Up Guide, Nigeria". "DOT" stands for "Directly Observed Treatment".

- "How long should the Role Model Caregiver observe each child after giving SMC medicines? a) 10 minutes, b) 15 minutes, c) 30 minutes, d) 1 hour, [Correct answer: C]" Malaria Consortium Quiz Answer Key.

- "What should the Role Model Caregiver advise the child’s caregiver after giving the first dose of the SMC medicines? a) When to take the second and third dose of amodiaquine (AQ) at home, b) The importance of adherence to giving the two doses of amodiaquine (AQ) home, c) What to do if the child vomits, d) How to mark the SMC Record Card after giving each dose and to bring the card back for the next SMC cycle, e) When to go to the health facility if the child gets a fever or very sick, f) All of above, [Correct Answer: F.]" Malaria Consortium Quiz Answer Key.

- "The child’s SMC Record Card is very important because: a) It shows the Role Model Caregiver the name and register number of the child, b) The child’s caregiver should always take it with them if they need to go to the health facility, c) It shows how many times the child received the SMC medicines each month, d) It is made of thick paper and is in a plastic packet, e) a, b and c, f) All of the above, [Correct answer: E.]" Malaria Consortium Quiz Answer Key.

- 24

Malaria Consortium, comments on a draft of this page, October 2019.

- 25

- "The child’s SMC Record Card is very important because: a) It shows the Role Model Caregiver the name and register number of the child, b) The child’s caregiver should always take it with them if they need to go to the health facility, c) It shows how many times the child received the SMC medicines each month, d) It is made of thick paper and is in a plastic packet, e) a, b and c, f) All of the above, [Correct answer: E.]" Malaria Consortium Quiz Answer Key.

- We have seen a few versions of templates for "SMC Record Cards." The latest version that we have seen (from 2016) is here: SMC Record Card Template 2016.

- 26

- See Figure 1, Pg 8, Malaria Consortium, "Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention Programme Start-Up Guide, Nigeria". "DOT" stands for "Directly Observed Treatment".

- "How long should the Role Model Caregiver observe each child after giving SMC medicines? a) 10 minutes, b) 15 minutes, c) 30 minutes, d) 1 hour, [Correct answer: C]" Malaria Consortium Quiz Answer Key.

- "What should the Role Model Caregiver advise the child’s caregiver after giving the first dose of the SMC medicines? a) When to take the second and third dose of Amodiaquine (AQ) at home, b) The importance of adherence to giving the two doses of Amodiaquine (AQ) home, c) What to do if the child vomits, d) How to mark the SMC Record Card after giving each dose and to bring the card back for the next SMC cycle, e) When to go to the health facility if the child gets a fever or very sick, f) All of above, [Correct Answer: F.]" Malaria Consortium Quiz Answer Key.

- Malaria Consortium told us that caregivers are able to visit CDs to request replacement doses if their child vomits. GiveWell's non-verbatim summary of conversations with Malaria Consortium staff, November 7 and November 9, 2016.

- 27

Malaria Consortium, comments on drafts of this page, October 2019 and October 2020.

- 28"An SMC campaign typically begins around five months before the start of the annual SMC round. This involves agreeing campaign dates and modalities at the national and state levels, as well as reflecting on lessons learned in previous years to inform adaptations to the SMC intervention tools and protocols. Micro-planning at the subnational level is conducted about four months before the start of the SMC round, including budgeting based on detailed enumeration of the target population at the subnational level, required personnel, and commodities." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 11

- 29“The manufacturing lead time can be up to 10 months and, consequently, orders need to be placed around one year before the start of the annual SMC round. The medicines need to be transported from the manufacturers’ production plants in China and India to ports in Africa, preferably by sea owing to the lower freight cost, or by air at a higher cost if the consignment is more urgent. Once the medicines have passed country-level customs and quality assurance procedures, they are distributed further using country-level supply chain mechanisms, typically to the state or health district level, the lowest administrative level where suitable storage facilities exist. In addition to SPAQ, SMC commodities include, for example, branded T-shirts, hijabs, bags, and pens, as well as items required to minimize the risk of COVID-19 infection among SMC implementers and communities, such as face masks and hand sanitizer. Last-mile distribution—the transport of commodities to the health facilities that serve as functional units for the SMC campaign —happens just before the start of SMC distribution. This can be challenging due to poor infrastructure and limited storage facilities. Supply management also involves reverse logistics, which is the process of transporting SMC commodities back to a central warehouse at the end of the cycle or annual round.” Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 12.

- 30"SMC implementers are trained through a cascade model beginning at the national level about two months before the start of the annual SMC round, with each cadre of trainers subsequently training the next lower level of trainers and learners. Community distributors are typically trained at the health facility level. SMC training includes modules on identifying eligible children, referring sick children to a health facility, administering SPAQ safely, recording SPAQ administration, interpersonal communication, and safeguarding. In some countries, separate trainings are conducted on supply chain management and health education." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 12.

- 31"During SMC distribution, community distributors are assisted by field supervisors who receive more in-depth training on supervision and mentoring skills. Each team of community distributors should be observed by, and receive constructive feedback from, a supervisor at least once every cycle. Supervision is coordinated by health workers at the health facilities that serve as functional units for SMC distribution, sometimes with support from community health workers. Malaria Consortium staff and local, regional, and central health authorities also support the supervision of SMC implementers." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 14.

- 32

"Community engagement is an important component of SMC campaigns to ensure high acceptability of the intervention among communities, as well as to encourage adherence to the SPAQ administration protocol by caregivers. Activities include sensitization meetings with local leaders, radio spots, and town announcers disseminating relevant information before and during the campaign." Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention program: Philanthropy report 2021, p. 12.

- 33

- "Budget: 1,694,339.00 (USD)" Malaria Consortium, "Support Scale up of Seasonal Malaria Chemoprevention (SMC)". We also searched the Gates Foundation's grant database to see whether it made any additional grants to Malaria Consortium for SMC work, but only saw this grant (grant page available at Gates Foundation, "Malaria Consortium").

- "Malaria Consortium is implementing and assessing the feasibility of a community-based seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) project in Katsina state, northern Nigeria, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Following new World Health Organisation policy recommendations on SMC, this project administers full antimalarial treatments during the malaria season in areas with highly seasonal malaria transmission, to prevent illness among children under five." Malaria Consortium, Project Brief: Seasonal malaria chemoprevention, Katsina, Pg 1.

- "The project’s objectives are:

- To design, in consultation with key local stakeholders, an appropriate community-based delivery system for SMC in Katsina state based on formative research, which will review aspects relating to feasibility, community acceptability, effectiveness and cost

- To launch and execute SMC delivery according to the selected delivery system and collect data on process indicators and costs

- To evaluate community acceptability, costs and effectiveness of the delivery system for SMC

- To inform future national and state plans for SMC continuation/ scale up by disseminating findings and sharing experiences with key stakeholders" Malaria Consortium, Project Brief: Seasonal malaria chemoprevention, Katsina, Pg 2.

- It appears that this project may have also been related to another major (£89 million) project that Malaria Consortium was working on in Nigeria called "Support to National Malaria Programme (SuNMaP)".

- "Support to National Malaria Programme (SuNMaP) is an £89 million UK aid funded project that works with the government and people of Nigeria to strengthen the national effort to control malaria. The programme began in April 2008 and [ended] in March 2016.

Led by Malaria Consortium, SuNMaP was jointly managed by a consortium, including lead partners Health Partners International and GRID Consulting, with nine other implementing partners. SuNMaP was implemented in 10 states across Nigeria, including Anambra, Kano, Niger, Katsina, Ogun, Lagos, Jigawa, Enugu, Kaduna and Yobe.

SuNMaP worked with the Nigerian government's National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP) to harmonise donor efforts and funding agencies around national policies and plans for malaria control. Project targets were aligned with the National Malaria Strategic Plan and Global Malaria Action Plan. The project aimed to improve national, state and local government level capacity for the prevention and treatment of malaria." Malaria Consortium, SuNMaP Final Report, Pg 38.

- "July 2013: Result of SuNMaP study on efficacy of sulphadoxine‐pyrimethamine (SP) for intermittent treatment against malaria in pregnancy published. SuNMaP commences seasonal malaria chemoprevention in Katsina State." Malaria Consortium, SuNMaP Final Report, Pg 16.

- "Support to National Malaria Programme (SuNMaP) is an £89 million UK aid funded project that works with the government and people of Nigeria to strengthen the national effort to control malaria. The programme began in April 2008 and [ended] in March 2016.

- 34

- Malaria Consortium emails (unpublished), November 23, 2016.

- "Length of project: 2012-2014 (33 months)," Malaria Consortium, Project Brief: Seasonal malaria chemoprevention, Katsina, Pg 1.