Note: This page summarizes the rationale behind a GiveWell-recommended grant to Malaria Consortium. Malaria Consortium staff reviewed this page prior to publication.

Amendment to this page

Since we published this page there has been an update to this grant. In June 2025, we recommended an additional $409,540 to Malaria Consortium to proceed with the 2025 seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) + vitamin A supplementation (VAS) campaign in Niger State, Nigeria, as planned. The campaign was at risk after SMC budgets were reduced, impacting Malaria Consortium’s ongoing implementation.

Context

In late May 2025, we were notified that, due to the challenging global funding landscape for malaria, the budget envelope for Malaria Consortium’s June 2025 SMC campaign in Niger State (which is not funded by GiveWell) was reduced. As a result, they were asked to increase the campaign’s daily targets and reduce supervision and training for the campaign. Malaria Consortium determined, and GiveWell agrees, that delivering VAS safely and effectively alongside SMC would not be feasible under these new parameters because distribution teams would not have time to communicate with parents about VAS side effects or check for risk of double dosing on top of their increased SMC workload.

We expect this additional funding will allow round 1 of the combined SMC + VAS campaign to take place as originally planned, increasing access to VAS for the estimated 1.68 million children targeted and potentially increasing the coverage of SMC as a result of lower daily targets and more training, supervision, and community sensitization.

Why we recommended this top-up grant

- We believe that this grant remains highly cost-effective even at a higher cost. We expect it to increase coverage of both VAS (substantially)1 and SMC (somewhat)2 across a large population with high mortality rates. Our cost-effectiveness (CE) estimate after including the cost of both the original grant and this top-up is 12x (75% CI range 8-17x) based on VAS benefits alone at the higher grant cost, and 18x if we include the more speculative benefits of increasing SMC coverage.

- We believe this campaign should continue as planned to reduce the potential harm of reduced VAS coverage as a result of the work to date. Due to the risk of harm from receiving double doses of VAS,3 Malaria Consortium had been working with Niger State to prevent VAS from being offered during the Maternal, Neonatal and Child Health Weeks (MNCHWs) that run in the same months as the SMC campaigns, prior to finding out about the reduced SMC funding availability. Without additional campaign funding, we expect the original GiveWell grant to Malaria Consortium for the SMC+VAS campaign in Niger state would likely reduce routine VAS access without providing any offsetting campaign-based access.

- We continue to see value in learning about the SMC + VAS layering model, and this additional funding should allow us to achieve the learning objectives set out in the original grant.

Our main reservations

- We’re quite unsure about the exact CE of this grant because:

- We have substantial uncertainty about coverage with and without this funding,

- We may not have sufficiently accounted for the overlapping benefits of VAS and SMC,4 and

- We conducted this investigation very quickly given the time sensitivity of the decision,5 raising the risk that we have missed something.

- It’s possible that by showing willingness to step in on a short-term gap in a time of budget reductions, GiveWell is creating a longer-term risk of crowding out other funders. We haven’t spent time exploring this possibility during the brief investigation for this grant, but feel this is unlikely given the small grant size and single-state scope of this grant. Plus, we think the strong case to make the grant outweighs this concern.

Amended: October 2025

In a nutshell

In October 2023, GiveWell recommended a $1.4m grant to Malaria Consortium to deliver vitamin A supplementation (VAS) alongside seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) campaigns in 2 states in Nigeria.

GiveWell recommended this grant because:

- We expect it will deliver VAS at low cost (we estimate $0.45 per child reached), because it leverages an existing platform for delivering SMC campaigns.

- We think that VAS is an effective program for reducing child mortality (best guess of a 3-5% reduction) in these states (where child mortality is high).

- We also think that funding this new approach to delivering VAS will provide learning benefits, and we have a very strong qualitative impression of Malaria Consortium.

Our main reservations about this grant are:

- Whether funding VAS through this program could reduce access to existing platforms for delivering VAS and other child health services in these states.

- We could fund another organization to support VAS instead using existing platforms, which could avoid some of the risks of a relatively untested program.

- We have some reservations about VAS in general, particularly the reliability of the evidence that it reduces child mortality and the applicability of that evidence to disease environments today.

Table of Contents

Published: January 2024

1. Summary

1.1 Background

Vitamin A deficiency (VAD) is a common condition in low-income countries that can lead to blindness, increased susceptibility to infection, and death.6 The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that 6 - 59 month old children in areas of high VAD receive vitamin A supplementation (VAS) two to three times per year to reduce child morbidity and mortality.7

VAS is one of GiveWell’s top-recommended programs, and we have previously funded two other organizations (Helen Keller Intl and Nutrition International) to support VAS campaigns.8 Our full research report for VAS is available here.

1.2 What we think this grant will do

This grant will fund Malaria Consortium to deliver VAS once per year in two states in Nigeria (Bauchi and Niger states) in 2024 (in both states) and 2025 (in Niger state only). Malaria Consortium already supports another child health program, seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), via door-to-door campaigns in these states. This grant will fund the additional costs of delivering VAS as part of these campaigns (e.g., additional training for distributors, and the extra costs of distributors reaching fewer children per day because they need to deliver an extra service).9

We think this grant will increase the number of children receiving VAS, and in turn avert a higher number of child deaths.

1.3 Why we made this grant

Our best guess is that this grant will be 17x (Niger state) to 54x (Bauchi state) as cost-effective as unconditional cash transfers (GiveWell’s benchmark for comparing different programs). At the time of writing this page, GiveWell’s funding bar is to fund grants that we estimate to be ~10x or more as cost-effective as cash transfers.

In simple terms, we think this grant will be cost-effective because:

- We think it will increase the number of children who receive VAS. In Nigeria, children can access VAS during routine healthcare appointments and biannual campaigns called Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Weeks (MNCHW), but we think (based on evidence from household surveys) that only ~35% to ~40% of children access VAS through these routes in Bauchi and Niger states. Based on Malaria Consortium’s previous pilots and surveys of its SMC program, we estimate that Malaria Consortium will reach 67% of children with this grant (albeit only once a year, while children will continue to have access to VAS through the other routes for the second recommended annual dose). (More)

- Child mortality is very high in northern Nigeria, where these states are located. We estimate the annual mortality rate for 6 - 59 month children is roughly 2% in Bauchi state and 1% in Niger state. (More)

- VAS probably reduces child mortality by a modest but meaningful amount. We estimate that receiving VAS will reduce a child’s mortality risk by ~3 - 5% in these states. This is based on a meta-analysis which finds that VAS reduces child mortality by 24%. We adjust this estimate down to account for improved child health since the underlying studies were conducted, our uncertainty about the reliability of the studies, and because this grant will only fund one round of VAS per year (rather than the normal two). (More)

- Co-delivering VAS alongside SMC is very cheap. Malaria Consortium’s SMC campaign platform already exists in both states, so the additional cost of delivering VAS alongside it is low. We estimate that it costs Malaria Consortium around $0.45 to reach each child with one round of VAS as part of this program. This is somewhat lower than our estimate of the one-round cost of reaching a child with VAS through Helen Keller Intl (~$0.65), which is already low relative to the other direct delivery programs GiveWell funds. (More)

Here is a summary of our cost-effectiveness analysis, using estimates for one state (Bauchi) as an example.

| What we are estimating | Best guess (rounded) | Confidence intervals (25th - 75th percentile) | Implied cost-effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Grant size (2024 only) | ~$600,000 | ||

| Child mortality benefits | |||

| Cost per child reached | $0.45 | $0.34 - $0.52 | 72x - 47x |

| Number of children receiving VAS | 1.3m | ||

| Proportion of children who would have received VAS without this program | 43% | 31% - 55% | 43x - 66x |

| Annual mortality rate among children who do not receive VAS | 2.1% | 1.6% - 2.6% | 42x - 68x |

| Reduction in mortality from receiving one round of VAS | 5% | 1% - 9.5% | 11x - 104x |

| Cost per death averted | $760 | ||

| Moral weight for each death averted | 119 | ||

| Cost-effectiveness estimate from mortality benefits | 47x | ||

| Value from different benefits | |||

| Percent of benefits from averted child mortality | 93% | ||

| Percent of benefits from income increases in later life | 7% | ||

| Additional adjustments | |||

| Adjustment for additional program benefits and downsides | +27% | +2% to +52% | 44x - 65x |

| Adjustment for diverting other actors’ spending into VAS | 0% | ||

| Adjustment for diverting other actors’ spending away from VAS | -15% | -34% to - 3% | 42x - 62x |

| Overall cost-effectiveness | 54x | ||

| Final cost per death averted | $880 | ||

You can see the simple cost-effectiveness analysis for this grant here and the full version here.

The other factors informing our decision to make this grant are:

- Malaria Consortium as an implementer (more). GiveWell has previously funded Malaria Consortium to deliver SMC in a number of countries, including Nigeria. Although this would be GiveWell’s first grant to Malaria Consortium for VAS, we expect that Malaria Consortium is well placed to deliver the program and will implement it to a high quality.

- Malaria Consortium has a track record of supporting SMC campaigns that achieve high coverage in Nigeria.

- It conducted two recent pilot studies testing co-delivery of VAS and SMC in Nigeria. We would expect this experience to inform its implementation and help it deliver the program to a high standard.

- Our qualitative assessment of Malaria Consortium as an organization is highly positive, even compared to GiveWell’s other top charities.

- Learning value (more). This approach to delivering VAS has the potential to be expanded to other locations where there are also SMC campaigns, but so far it has only been tested in two small pilots. Making this grant could help us understand how promising the approach is for scale-up elsewhere (e.g. whether Malaria Consortium is able to achieve high coverage at scale, and whether there are unanticipated problems we haven’t considered). Malaria Consortium is also planning to conduct additional monitoring alongside the program to help us understand what impact it has on the delivery of existing health services (e.g. by tracking coverage of interventions like deworming—that are normally delivered alongside VAS—over time).

1.4 Main reservations

- Will this grant reduce access to existing child health services? During our grant investigation we heard some feedback that this approach to delivering VAS could reduce access to existing child health platforms. This could happen via reducing VAS coverage during the other campaign round (e.g. if caregivers start to expect to receive VAS at home rather than at clinics), or by reducing coverage of other child and maternal health services that are normally co-delivered alongside VAS, such as deworming, if caregivers are less motivated to go to health clinics because they’ve already received VAS. We try to account for these risks in our analysis, but we could be underestimating the risk. Malaria Consortium is planning to conduct additional monitoring as part of the grant to gather more evidence about how big a problem this is. (More)

- Should we fund another VAS implementer in these locations using existing platforms? Considering the risks of a relatively new approach, an alternative would be to fund another organization (e.g. Helen Keller Intl or Nutrition International) to support VAS delivery using the existing VAS platform in these states. This would also mean we could fund two rounds of VAS per year rather than just one. (More)

- Wider uncertainties about VAS. We have a number of other questions about VAS programs that are not specific to this grant. These include (more):

- The impact of VAS on mortality. While our analysis of VAS is underpinned by a meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials, we have some doubts about this evidence (e.g. some studies finding little or no impact for unclear reasons, most studies being conducted in the 1980s and 1990s when disease environments were different). This means we’re unsure what impact VAS will have on mortality today.

- Vitamin A deficiency rates. We expect that vitamin A status is the main mediator of the impact of VAS on mortality, but data on deficiency rates today is relatively limited. In recent years many countries have introduced programs to fortify staple crops with vitamin A, and it’s possible this means that deficiency rates have fallen faster than we expect. Anecdotally, we have heard that a recent survey in Nigeria found low prevalence of deficiency. Our understanding is that the survey hasn’t yet been published, and so we haven’t yet been able to review the results. If the survey finds deficiency is lower than we currently estimate, this would reduce our estimate of the impact of the program. We plan to review data from this survey if and when it becomes available.

- Are there drawbacks to VAS campaigns we are missing? We think that VAS is one of the most cost-effective programs donors can support. However, our understanding is that there is relatively little investment in VAS from other global health funders. This raises a concern that there are drawbacks to VAS that we are missing.

Funding for the grant

This grant was funded by the Rauch Family Foundation, on GiveWell's recommendation.

2. Planned activities and budget

2.1 Background

In Nigeria, VAS is normally distributed with other maternal and child health services (e.g. deworming, nutrition screening, iron & folic acid supplementation)10 in campaigns called Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Weeks (MNCHW). These campaigns are organized by the health authorities in each Nigerian state.11 These are meant to take place twice a year and involve delivery of VAS at health clinics, with outreach events to more remote areas.12

GiveWell currently funds another organization, Helen Keller Intl, to support VAS through these campaigns. In 2023, GiveWell funded Helen Keller Intl to support VAS through this platform in five states.13 However, in many non-GiveWell supported states in Nigeria, we believe that the proportion of children receiving VAS through this platform is relatively low (more below).

2.2 What we think this grant will do

This ~$1.4m14 grant will fund Malaria Consortium to deliver VAS to 6 - 59 month olds in 2 of Nigeria’s 36 states (Bauchi state and Niger state). The grant funds delivery of VAS in Bauchi state in 2024 only, and Niger in both 2024 and 2025 (reasoning in footnote).15

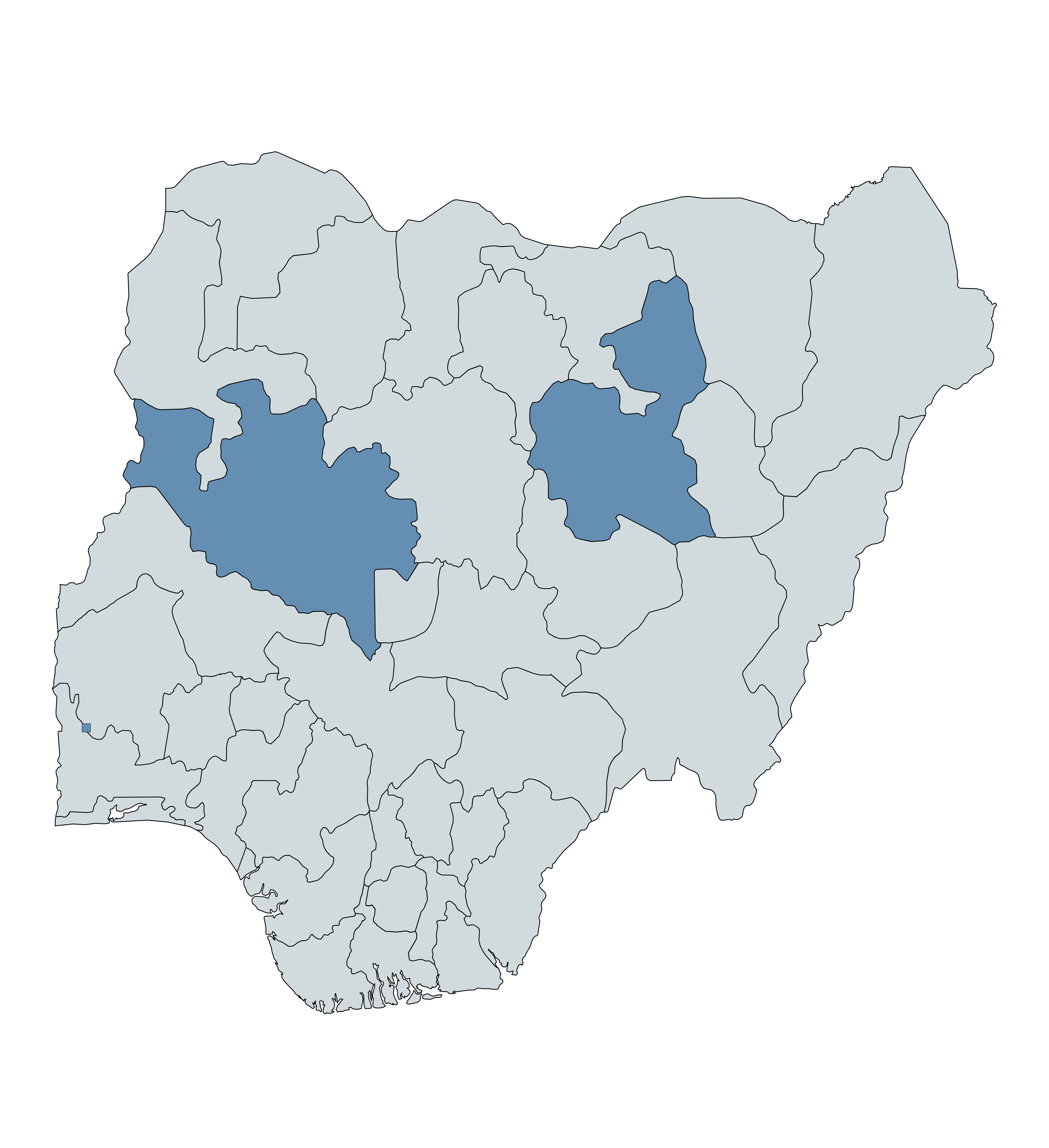

Niger and Bauchi states are highlighted in blue.16

Malaria Consortium’s seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) program already operates in both states. To deliver SMC, community distributors funded and trained by Malaria Consortium go door-to-door each month for 4-5 consecutive months to deliver antimalarial drugs to young children.17

We expect this grant will fund the costs of delivering 1 round of VAS to children alongside SMC. In particular, the grant will fund training for distributors to administer vitamin A supplements and additional labor time that distributors will require to provide an extra service on top of SMC.18 Malaria Consortium expects that it will deliver VAS as part of the final SMC cycle in each state (in October).19 Community distributors will be instructed to give the SMC drugs to children first, and then deliver VAS after a 30 minute wait (to ensure the child does not vomit up the drugs).20 VAS is delivered by cutting open a capsule containing vitamin A in solution and squeezing the contents into children's mouths.21

Malaria Consortium has conducted 2 previous pilot studies testing this approach. These were in Sokoto state in 2019 and Bauchi state in 2021. Malaria Consortium told us that VAS was removed from the services available in the closest MNCHW campaign round in the locations where the pilots took place. In the other MNCHW campaign round, VAS was provided as normal. Malaria Consortium told us that it expects the same model to apply for this grant.22

This grant will solely cover the additional costs of delivering VAS alongside SMC. It includes the cost of procuring VAS capsules, although Malaria Consortium may be able to get these donated for free (details in footnote).23 Malaria Consortium is also planning to conduct some additional monitoring as part of this program, but this will be funded by a separate research funding pot and is not included in this grant. (More)

3. The case for the grant

3.1 Cost-effectiveness

Our best guess is that this grant will be 17x (Niger state) to 54x (Bauchi state) as cost-effective as unconditional cash transfers (GiveWell’s benchmark for comparing different programs). At the time of writing this page, GiveWell’s funding bar is to fund grants that we estimate to be ~10x or more as cost-effective as cash transfers.24 The main benefit that we expect from this grant is reduced child mortality. Our best guess is that the grant will avert ~960 child deaths25 from reduced infectious disease.

We set out the reasons why we think VAS is generally a cost-effective intervention in our separate report on VAS. The main reasons we expect this specific grant to be cost-effective are discussed below.

Impact on VAS coverage

We think this grant will increase the number of children who receive VAS. This is based on our analysis of two factors:

- The proportion of children who would receive VAS without the program

- In Nigeria, children can access VAS during routine healthcare appointments and biannual campaigns called Maternal, Newborn and Child Health Weeks (MNCHW).26

- As part of our grant investigation, we estimated the proportion of children who would be reached through these routes if we did not provide funding for Malaria Consortium’s program. We refer to this estimate as “counterfactual VAS coverage.” In general, the higher this proportion, the less additional impact we think our funding will have.

- Our estimates of counterfactual VAS coverage are based on 4 household surveys conducted in northern Nigeria between 2018 and 2023 that asked caregivers whether their child received VAS in the prior 6 months (compiled in this spreadsheet). Using our preferred assumptions, we estimate that 39% (Bauchi state) / 37% (Niger state) of children in the overall target population would receive VAS in the absence of GiveWell funding, and 43% (Bauchi state) / 40% (Niger state) of children that will be reached by Malaria Consortium with GiveWell funding would receive VAS in the absence of this funding (discussion in footnote).27

- We have higher confidence in our estimates for Bauchi state (where we have 2023 data from surveys conducted by Malaria Consortium as part of its regular SMC program monitoring) than Niger state (where we don’t). Our Niger state estimates are based solely on two household surveys conducted in 2018. We decided not to adjust these estimates because (a) they are in the same range as other states and (b) like many of the other states included in our analysis, we think Niger state is one of the states receiving the least support from external funders for VAS. (details in footnote).28

- The proportion of children who will receive VAS with the program

- Our best guess is that 67% of targeted children will receive VAS through Malaria Consortium’s program (albeit only once a year, while children will continue to have access to VAS through the other routes for the second recommended annual dose).

- This estimate is based on post-campaign survey data from Malaria Consortium’s 2 earlier pilots (in Sokoto state in 2019 and Bauchi state in 2021) testing co-delivery of VAS and SMC. These surveys found 59% and 82% VAS coverage respectively. We also put some weight on coverage data from its SMC program in Nigeria between 2018 and 2021, which found 78% coverage overall.29

- Note that this estimate reflects only the proportion of children that we think will be reached by Malaria Consortium’s campaigns, not the overall proportion of children who will receive VAS in these states. We expect this latter proportion will be higher, since some children will still have access to VAS through other routes (e.g., as part of Nigeria’s routine immunization schedule).30 Discussion in footnote on how we account for this distinction quantitatively.31

High child mortality in these states

Child mortality is very high in northern Nigeria, where Niger state and Bauchi state are located. Our estimates of child mortality are based on estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Project (GBD), to which we apply several adjustments.32 Overall, we estimate that the annual child mortality rate for 6 - 59 month old children is around 1% in Niger state and 2% in Bauchi state. These mortality rates are relatively high compared to other locations where GiveWell funds VAS programs (range of 0.67% to 1.76%).33 While we’re uncertain about the GBD estimates,34 this fits with our impression from other sources that child mortality in northern Nigeria is particularly high.35

Impact on all-cause child mortality

VAS probably reduces child mortality by a modest but meaningful amount. We estimate that receiving one round of VAS reduces a child’s mortality risk by ~3% in Niger state and ~5% in Bauchi state.

Our main estimate of the mortality impact of VAS is based on a meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials (Imdad et. al. 2017) that finds VAS reduces child mortality by 24%.36 We adjust this estimate down to account for improved child health since the underlying studies were conducted and our uncertainty about the reliability of the studies. See these rows in our main VAS cost-effectiveness analysis for more details on our reasoning.

For this grant, we produced a new estimate of the impact of a single round of VAS on mortality. To date, GiveWell has only funded programs that aim to deliver two rounds of VAS per year, and most studies in the meta-analysis we rely on tested two or three annual rounds of VAS.37 By contrast, Malaria Consortium’s program will only deliver a single round of VAS per year.

Our best guess is that a single round of VAS is 57% as effective at reducing mortality as two rounds per year. We then adjust this downward to 53% to account for Malaria Consortium’s program altering the interval between campaigns (details in footnote).38 Our analysis is based on two main elements:

- Prior estimate: A best guess that one round of VAS is slightly more than half as effective (55% impact on mortality) as two rounds, due to a diminishing returns effect (i.e., the first dose provides strong protection against mortality, with each successive dose providing relatively less protection).

- Evidence from VAS trials: We also assign a small amount of weight (10%) to two studies in the meta-analysis that tested one round of VAS and had 12 month follow-up periods. We use these studies because we’d expect these studies to be the closest guides to the impact of Malaria Consortium’s program (which will also deliver one round of VAS per year).39 The overall weighted reduction in mortality in these studies was larger than we’d expect (-18%) based on our prior (-13%), leading us to update our overall estimate upward. However, we only assign a small amount of weight to these studies because we would expect data from just 2 trials to be noisy, and so together they comprise less than 10% of the overall meta-analysis weight.40

See this spreadsheet for our full reasoning and calculations. Overall, we’re uncertain about this estimate, which is based on limited empirical data and only a light-touch review. We hope to improve our analysis on this question in the future (e.g., through conversations with VAS experts).

Co-delivering VAS alongside SMC is very cheap

We estimate that it costs Malaria Consortium around $0.45 to reach each child with one round of VAS as part of this program. This is somewhat lower than our estimate of the one-round cost of reaching a child with VAS through Helen Keller Intl (~$0.65)41 , which is already lower than most other direct delivery programs GiveWell funds.

Our estimate of the cost per child reached with VAS is based on a cost projection of $0.30 per child targeted shared by Malaria Consortium and our estimate that the program will reach 67% of these children.42 Our understanding is that the $0.30 cost projection was based on a costing study conducted by Malaria Consortium as part of its earlier Bauchi pilot of the program in 2021, that found the program cost was $0.24 per child reached.43 It then increased this estimate to account for increasing costs over time44 (a rough GiveWell analysis suggests that this was approximately a 40% increase in costs, details in footnote).45 We think that Malaria Consortium’s estimates seem reasonable, although we didn’t closely investigate the assumptions used or try to understand the methodology of the costing study in detail.

Our intuition for why this program is so cheap is that Malaria Consortium’s SMC campaign platform already exists in both states. The fixed costs of setting up and administering this platform have already been incurred, and so the additional cost of delivering VAS alongside it is low.

Other cost-effectiveness analysis updates

As part of our grant investigation, we also made a number of other updates to our cost-effectiveness analysis. These are discussed in a footnote.46

3.2 Malaria Consortium as an implementer

GiveWell has previously funded Malaria Consortium to support SMC campaigns in a number of countries, including Nigeria (more details on our separate report on its SMC program). Although this would be GiveWell’s first grant to Malaria Consortium for VAS, we expect that Malaria Consortium is well placed to deliver the program and will implement it to a high quality. Reasons to think this include:

- Malaria Consortium has a track record of supporting SMC campaigns that achieve high coverage in Nigeria. Our analysis of its surveys found an overall coverage rate of 78% between 2018 and 2021. We think that its door-to-door delivery platform for SMC is a key reason for this high coverage rate, and will have similar benefits for coverage of VAS.

- Malaria Consortium conducted two recent pilot studies testing co-delivery of VAS and SMC in Nigeria. We would expect this experience to inform its implementation and help it deliver the program to a high standard. For example, Malaria Consortium made a number of changes to the program in response to the Sokoto pilot’s findings (e.g. reducing community distributors’ daily targets for the number of children reached and adding an additional day to the distribution period because of concerns about overwork).47

- Our qualitative assessment of Malaria Consortium as an organization is highly positive. We think it is transparent, thoughtful, and has staff with a high level of operational and technical expertise. When we have requested feedback on Malaria Consortium from national malaria programs and other malaria contacts, we have generally heard positive (and often very strongly expressed) comments. More in this section of our report on Malaria Consortium’s SMC program.

3.3 Learning value

This approach to delivering VAS has the potential to be expanded to other locations where there are also SMC campaigns, but so far it has only been tested at small scale in Malaria Consortium’s initial pilots. We see this grant as an opportunity to understand how effective the program is at scale.

Specific questions we hope to answer as a result of this grant are:

- What impact will the program have on VAS coverage? This will be collected via a VAS question48 in surveys conducted by Malaria Consortium before and after the campaign is delivered.

- What impact will the program have on other interventions normally delivered alongside VAS? As we discuss below, one of our key reservations about this grant is that it could reduce coverage of other health services (e.g., deworming) normally co-delivered with VAS in the MNCHW campaigns.

- How do the Nigeria health authorities (at the federal and state level) respond to the program? We have asked Malaria Consortium to share ad hoc feedback on how the authorities and other partners are responding to the program to understand this. We may also seek out conversations with these partners.

Malaria Consortium is planning to conduct additional monitoring as part of the program to help us answer these questions. Before we made the grant, we agreed with Malaria Consortium that this work would be funded out of a separate research budget it holds and so is not included in this grant decision. At the time of writing, we have not yet agreed on a monitoring approach with Malaria Consortium, but our initial proposal to Malaria Consortium includes49 :

- A baseline survey to gather data on coverage of VAS and other interventions co-delivered alongside VAS (e.g., deworming).

- 3 subsequent survey waves to gather data on coverage of the same interventions immediately after the Maternal and Newborn Child Health Weeks.

- 3 waves of qualitative interviews with health clinic staff to understand their perspectives on the program and its impact on the Maternal and Newborn Child Health Weeks.

We hope that this approach will provide us with evidence on the impact of the program on existing health services. However, it’s possible that the monitoring will be less informative than we hope (e.g., because a before-and-after design is not able to isolate the impact of Malaria Consortium’s program from other factors that affect MNCHW coverage).

4. Risks and reservations

Risk of reducing access to existing child health services. In the external conversations we had while investigating this grant, we heard some concerns that this approach to delivering VAS does not adhere to the national strategy for delivering vitamin A, and could reduce access to other child health services delivered through the MNCHW. VAS campaigns are meant to take place twice a year in Nigeria, and this program would only deliver VAS once a year, using a different campaign platform (more above).

This raises concerns about the program including:

- It could reduce VAS coverage during the other annual campaign round (e.g. if caregivers start to expect to receive VAS at home and are less motivated to travel to clinics).

- It could reduce coverage of the other child and maternal health services that are normally co-delivered alongside VAS, such as deworming, if caregivers are less motivated to go to health clinics because they’ve already received VAS.50

- It could change the interval between VAS rounds. Malaria Consortium expects to deliver VAS in October, whereas the second VAS campaign round may take place in the months after this.51 This means that children who receive both annual VAS rounds are likely to receive VAS ~4-5 months after the previous round, followed by a ~7-8 month gap (rather than every 6 months). We’re unsure what impact this could have on the effect of VAS on mortality.

We have attempted to account for these concerns in three ways, although we’re unsure about each of them:

- Adjustment for negatively impacting other programs. Our cost-effectiveness analysis includes a -15% adjustment to account for the risk of harming coverage of other interventions. This is because we think that this concern is plausible. However, the specific adjustment we use should be considered a very rough guess, and is not based on any empirical evidence.

- Monitoring the impact of the program on other interventions. Alongside this grant, Malaria Consortium has agreed to conduct additional monitoring to understand whether this funding is reducing the proportion of caregivers accessing other health services (more above). We expect that this will provide data to update our -15% best guess (e.g., via household surveys to understand coverage of other services before and after the program is delivered). However, at the time of writing, we have not finalized the details of this monitoring with Malaria Consortium. It’s possible that the evidence it gathers will be less informative in answering this question than we expect.

- Adjustment for changing the interval between VAS campaigns. We incorporate a -5% adjustment into our estimate of the impact of VAS on child mortality. This is designed to account for the risk that this program will alter the interval between VAS campaigns, and that this will make VAS less effective at averting mortality. Our adjustment is based on (i) our estimate of the impact of each round of VAS (discussed above), (ii) guesses about the impact of changing the interval between rounds on mortality and (iii) an estimate of the proportion of children who will receive VAS outside this program (details in footnote).52 This adjustment should also be considered a rough estimate, and is not based on any conversations with experts.

Should we fund another VAS implementer in these locations using existing platforms? Co-delivery with SMC is a relatively new approach to delivering VAS. Considering the risks we describe above, an alternative would be to fund another organization (e.g., Helen Keller Intl or Nutrition International) to support VAS delivery using the existing MNCHW platform in these states. This would also mean we could fund two rounds of VAS per year rather than just one.53

On balance, we have decided against doing this because:

- We think this program is likely to be a particularly effective use of funding, because the costs of layering VAS onto the SMC platform are very low (more above).

- The learning value of trying a new approach and gathering evidence about how well it works. This could help inform decisions about whether to scale up the program in more locations in the future.

- Our qualitative assessment of Malaria Consortium is particularly positive (more above).

Other reservations about VAS. We have a number of other questions about VAS programs that are not specific to this grant. These include:

- The impact of VAS on mortality. We estimate that receiving VAS as part of this grant will reduce all-cause child mortality by 5% (more above). This is based on a meta-analysis of 19 randomized controlled trials (Imdad et. al. 2017). However, we have a number of reservations about this evidence, including:

- How to interpret variation between studies of VAS. Most of the studies in the meta-analysis took place in the 1980s and 1990s. Two out of the three more recent studies found lower effect sizes than the older literature.54 This includes the DEVTA trial, whose sample size is larger than the combined sample size of the remaining studies.55 We don’t know how to account for this variation between studies.

- We don’t have a clear understanding of how vitamin A reduces the risk of infectious disease mortality.56 This makes it hard to know what we should expect the mortality impact of VAS should be today, in a different disease environment to when the studies were originally conducted.

- Vitamin A deficiency rates. We think vitamin A status is the main mediator of the impact of VAS on mortality. This means our analysis is sensitive to the rate of deficiency in locations where we fund VAS today. But we’re uncertain about contemporary deficiency rates and have relatively little high-quality data with which to estimate them. In Nigeria, the latest survey data we have seen is from a national survey conducted in 2001. We then adjust these to account for change over time and to create state-level estimates using more recent data on indicators we think may be proxies for deficiency (e.g. poverty rates, anemia rates).57

We would expect this method to be relatively imprecise. Since the survey was conducted, Nigeria has introduced programs to fortify staple crops58

, but we’ve seen little evidence on how effective this has been. It’s possible that these programs mean deficiency rates are lower than we expect, implying we’re overestimating the impact of VAS.

- Another reservation is that, before we finalized this grant, we heard an anecdotal report of a new vitamin A deficiency survey in Nigeria finding low VAD prevalence. Our understanding is that this survey has not been published yet, and so we haven’t yet been able to review the results. If this survey finds deficiency is lower than we currently estimate, this could reduce our estimate of the impact of the program. We plan to review data from this survey if and when they become available.

- Are there drawbacks to VAS campaigns we are missing? We think that VAS is one of the most cost-effective programs donors can support. However, our understanding is that there is relatively little investment in VAS from other global health funders. This raises a concern that there are drawbacks to VAS that we are missing.

5. Plans for follow up

- We will have occasional calls with Malaria Consortium to discuss its work, including progress on its negotiations with the health authorities and partners in each state and the process for applying for vitamin A capsule donations.

- We will discuss and agree details for monitoring of the program (discussed above). We expect this to include discussions about GiveWell’s research objectives, Malaria Consortium submitting a research protocol, and GiveWell giving feedback on that protocol.

- We will use data from Malaria Consortium’s post-campaign survey (expected October 2024) to decide whether or not to disburse the 2025 funding for Niger state. We also expect to make a decision about whether to renew funding for Bauchi state around this time.

Update added July 2025:

- In January 2025, we approved 2025 funding for Niger state. This is because we thought there are significant learning benefits to funding a second year of the program.

- This is partly because there was a minor implementation issue in year one that Malaria Consortium thinks will not be repeated in year two, so we'll have data from a more optimal version of the program.59

- In addition, we have refined our understanding of the data that would be most useful in our assessment of the program's cost-effectiveness, and we think Malaria Consortium will be open to updating its monitoring to gather some additional information. This includes:

- Tracking responses from caregivers reporting that their child received multiple doses of VAS in the last six months.

- Assessing immunization coverage during MNCHWs with and without VAS, to inform our understanding of the risk that immunization coverage at MNCHWs is reduced due to the program. We think this could be one of the most important program downsides.

- In January 2025, we approved rolling funding for Bauchi state forward from 2024 to 2025.

- Malaria Consortium told us that they were unable to implement the program in Bauchi in 2024. This was because Malaria Consortium was unable to reach agreement with the government to remove VAS from the MNCHW proximate to the co-delivered VAS/SMC campaign,60 and we (GiveWell) were not comfortable going ahead with parallel delivery due to our concerns about the risk of adverse events if children receive two doses in close proximity.61

- Malaria Consortium believes it will reach an agreement with the government in 2025 to implement the program as planned.62

- We expect to make a decision about whether to renew the program in each state in 2026 in early 2026.

6. Internal forecasts

| Confidence | Prediction | Date |

|---|---|---|

| 85% | Malaria Consortium will obtain permission from state health authorities and deliver the program in at least 70% of local government authorities (LGA) in at least one state in 2024. | By 12/31/2024 |

| 65% | …Both states (Niger and Bauchi). | By 12/31/2024 |

| 80% | Malaria Consortium’s post-round surveys in October 2024 will give a VAS coverage estimate above 55% in both states included in this grant. | By 12/31/2024 |

| 90% | …above 55% in at least 1 state. | By 12/31/2024 |

| 80% | Malaria Consortium is able to obtain donated capsules for at least 75% of the children targeted by the program in 2024. | By 12/31/2024 |

| 50% | Conditional on Malaria Consortium conducting a baseline VAS coverage survey, a simple average of baseline VAS coverage in states funded by our grant will be above 40%. | By 12/31/2024 |

| 25% | …Above 50%. | By 12/31/2024 |

| 75% | …Above 25%. | By 12/31/2024 |

| 60% | Conditional on Malaria Consortium conducting monitoring of the impact of its program on other health services, GiveWell will conclude that the program reduced coverage of deworming in the target states by more than 10% overall between summer 2023 and the end of 2025. | By 12/31/2025 |

| 30% | …By more than 20%. | By 12/31/2025 |

7. Our process

We identified this grant opportunity through conversations with Malaria Consortium. As part of our grant investigation process, we had conversations with Malaria Consortium and two other VAS implementing organizations: Helen Keller Intl and Nutrition International.

To generate a grant-specific cost-effectiveness estimate, we used our existing cost-effectiveness model for VAS and updated various parameters to match the specifics of this program.

For internal review, a Senior Program Officer gave feedback on various aspects of the grant investigation, and a Senior Research Associate gave feedback on our estimate of the impact of one round of VAS on mortality.

Sources

| Document | Source |

|---|---|

| DEVTA (2013) | Source |

| Fisker et al., 2014 | Source |

| GiveWell, 2023 GiveWell cost-effectiveness analysis – version 4 | Source |

| GiveWell, Counterfactual VAS coverage estimates for codelivery grant, 2023 | Source |

| GiveWell, GiveWell's 2020 moral weights | Source |

| GiveWell, GiveWell's analysis of Malaria Consortium's cost per SMC cycle administered, 2022 | Source |

| GiveWell, Helen Keller distribution methods for VAS mass distribution campaigns [2022] | Source |

| GiveWell, Hellen Keller International — Vitamin A supplementation (January 2023) | Source |

| GiveWell, How we produce impact estimates, 2023 | Source |

| GiveWell, Malaria Consortium – seasonal malaria chemoprevention | Source |

| GiveWell, Malaria Consortium – seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC), 2023 | Source |

| GiveWell, Malaria Consortium VAS grant breakdown, 2023 | Source |

| GiveWell, Mass distribution of azithromycin to reduce child mortality, 2019 | Source |

| GiveWell, Nutrition International — Vitamin A supplementation renewal, Chad (May 2023) | Source |

| GiveWell, Revisiting leverage, 2018 | Source |

| GiveWell, Round 1 VAS effect size estimate, 2023 | Source |

| GiveWell, Seasonal malaria chemoprevention, 2018 | Source |

| GiveWell, VAS CEA for SMC codelivery grant, 2023 | Source |

| GiveWell, Vitamin A supplementation, 2018 | Source |

| Helen Keller International, 2023 room for more funding report | Source |

| Helen Keller International, Tanzania social mobilization toolkit: VAS administration guide | Source |

| IGME, Levels and trends in child mortality, 2022 | Source |

| IGME, Nigeria under-5 mortality rate | Source (archive) |

| Imdad et al., 2017 | Source |

| Malaria Consortium, "Integrating seasonal malaria chemoprevention and vitamin A supplementation: Lessons learnt from Nigeria" 2022 | Source |

| Malaria Consortium, 2021 coverage report | Source |

| Malaria Consortium, 23-09 VAS Coverage Nigeria - Malaria Consortium data | Source |

| Malaria Consortium, SMC philanthropy report 2022 | Source |

| Maziya-Dixon et al. 2006 | Source |

| Oresanya et al., 2022 | Source |

| UNICEF, Evaluation of the Maternal Neonatal and Child Health Week in Nigeria, 2016 | Source |

| Venkataro et al., 1996 | Source (archive) |

| World Bank, Accelerating Nutrition Results in Nigeria (P162069) project summary, 2018 | Source (archive) |

| World Health Organization, "Guideline: Vitamin A supplementation in infants and children 6-59 months of age, 2011 | Source |

| World Health Organization, Vaccination schedule for Nigeria | Source (archive) |